The Living Bog is actively working in the local communities surrounding our sites to collate as much information as possible about our bogs, and to record the local stories about the local bog that otherwise may well be lost in the passage of time. What is ordinary to those who may have lived there, or who heard stories or local folklore may well be extraordinary to those from elsewhere.

With that in mind, we asked Seamus Crawley of the Gortaganny Development Association to raid his own personal archives, and with the help of Seamus Kenny the following contains some extraordinary local history: Evidence of an important Togher Road (then and now) and of spuds in the bog! Enjoy!

The general area of west Roscommon and east Mayo extensive area is primarily that of a mix of arable land and bogland with a number of interspersed lakes. All records allude to lake connectivity via streams, rivers and indeed underground water passages/streams often referred to as ‘sinking rivers’. The landscape and associated quality is noted as been influenced by the extensive limestone content and turloughs in the area.

As regards the bogland specifically in the area, a feature of the general landscape is the mixture of arable lands in more elevated areas with drumlin-like, or esker-like, features. As regards the bogland itself, it is likely that the extensive bog areas were manipulated by ancestral populations over many years.

While noting that detailed archaeology studies could confirm much greater information, there are a couple of initial research examples that are worthy of further investigation.

-

TOGHER ROAD

In the late 18th and early 19th century in a pre-famine Ireland, extensive land and mapping surveys were conducted around West Roscommon. Some of the surveys were conducted by legislators, ordinance officers or, in many cases, by local landlords.

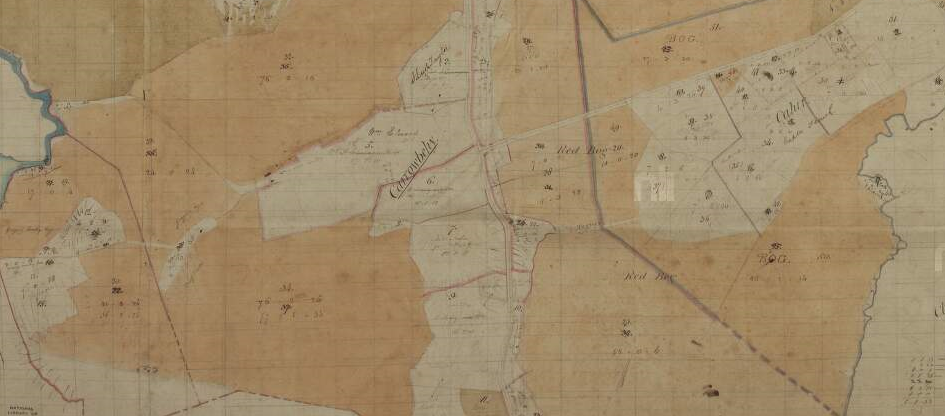

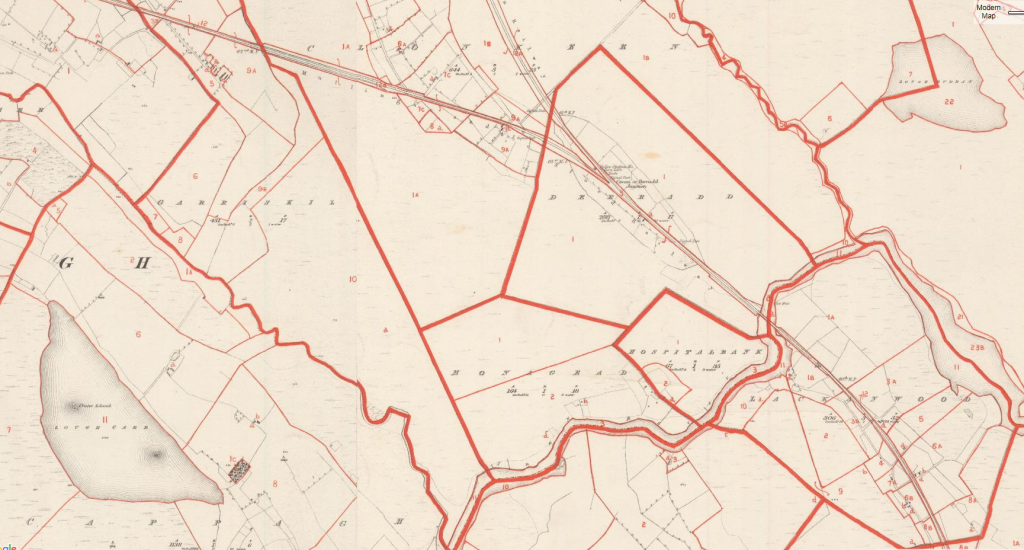

Below is a copy of a more extensive map survey area of Carrowbehy district (from National Library archives) which record a ‘Togher Road’ clearly defined between the land mass area of Cahir and Carrowbehy, between the old ‘Red Bog’ names of the bog.

The survey was conducted in March 1830 and compiled in subsequent weeks. This road is typical of a likely location of a ‘togher’ which were extensively used and improved by local farmers in the Bronze Age and into the pre-Christian Iron Age.

The purpose of these trackway types made of wood was simply as a suitable method of passing undrained marshy land masses. The most intriguing detail relevant to the recording of this togher road is that it was recorded in the respective survey and may suggest that it maybe still in use or at the very least it still left a mark on the local landscape. Indeed, it may be probable that the ancient trackway was modernised by the use of stone and elevated to some extent accordingly. You can see it marked more clearly below.

Regardless, the fact it was recorded and where it was located opens up a great opportunity for research purposes relative to this ‘togher’ location and indeed the likelihood of more of this trackway type around Carrowbehy bog. The actual topography of this road and map area could easily suggest the most likely locations of other ‘Togher’ road types in Carrowbehy bog.

WHERE IS IT TODAY?

From the outset, the most relevant concern that needs to be examined is ‘where is this road today?’ Firstly, the march of subsequent progress in the district may offer a likely possibility. Noting that this map was a pre-famine survey, the more modern link road from Ballyhaunis to Loughglynn was improved in circa 1860s. This new road would have crossed this Togher road. The concern may be that any material on this Togher road may have found its way on to the new improved road. It is worth checking in any case!

(Also note that this map of 1830 does not record the ‘New Line’ road in Erritt. This may suggest that this road was most likely constructed in the 1830’s)

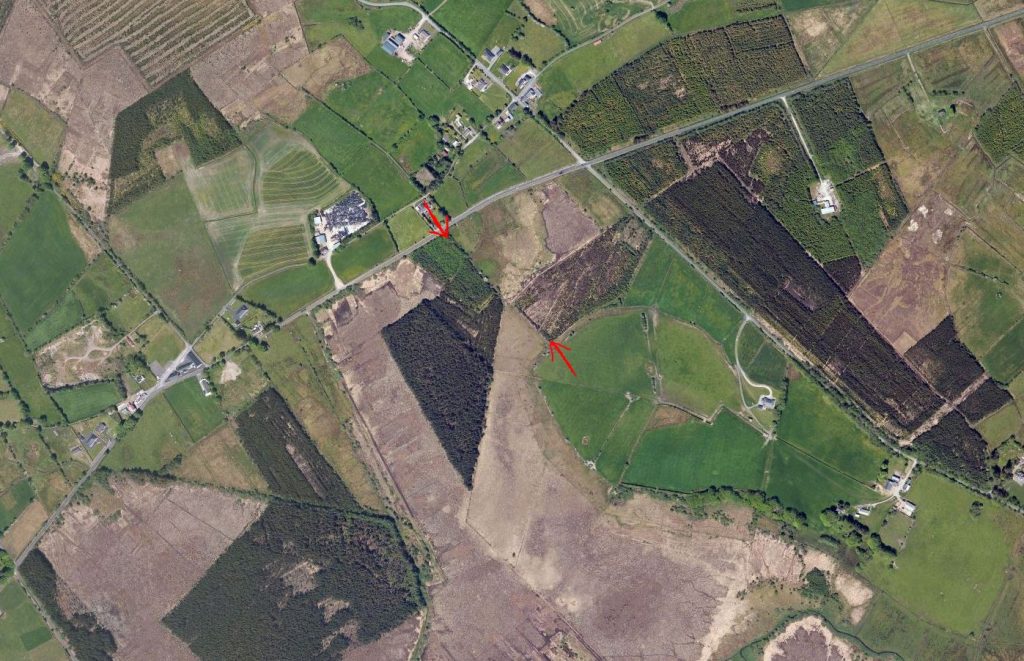

The Living Bog had a go at layering maps, with thanks to the OSI for allowing us to use their online maps. We overlayed the 1830’s map onto a current aerial view.

An overlay of the historic map onto a more recent OSI map.

Using OSI maps, here is another look at the two eras with the Togher Road in the centre of the photo.

From overlaying the old maps onto more recent aerial imagery, it’s clear the ‘path’ of the old Togher Road is still there, alongside some forestry. It has been covered over substantially in recent years, and if not dissolved or disappeared it may well be subsumed by the march of earth and growing bog.

What is interesting to see if how the landscape changed in this small area over the course of almost 200 years. Where turf was not cut by traditional means, the old ‘Red Bog’ was forested and later reclaimed and put into use as agricultural land. Much of Ireland’s bogland was afforested over the last 150 years, quite a bit with non-native trees. Other LIFE projects in Ireland have concentrated on removing some of this forestry with some degree of success.

If you look at a recent clean aerial shot (from Bing Maps), you can still see the line of the Togher Road (between the red arrows), despite the changes to the surrounding landscape.

Aerial view from Bing Maps 2017: The area where the Togher Road was in indicated between the two arrows.

-

CULTIVATION OF BOGLAND aka ‘SPUDS ON THE BOG’

A more modern synopsis of farming practises in the 19th century notes the increased populations in West Roscommon and the country in general and the attempts to utilise bogland areas for more liveable and active agricultural purposes. This can be attributed to some marshy or cutaway lands that have been used for semi-arable farming and grazing purposes.

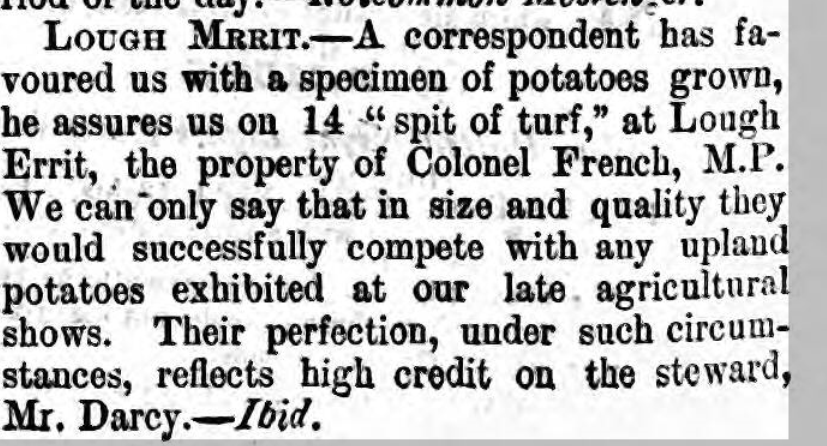

After the famine and the continual human burden of survival, the local steward of the Erritt Lodge estate conducted a research project in attempting to facilitate bogland area to grow potatoes of an acceptable standard.

Details attached from 1870 newspaper.

It is likely that this was a feature of both pre-famine and post famine activities in growing potatoes in bogland area. However, the attached detail seems to declare a more national newsworthy success in enabling the growth of potatoes!

This story adds to the extensive details recorded in both the Dillon and De Freyne estates in attempts in utilising bogland for more agriculturally productive requirements. Again, this detail is not of relevance to an ancient or medieval use of boglands, but it does illustrate ways that local communities tried to utilize and improve the use of boglands around Carrowbehy and district for more agricultural productive purposes in times past. (Other examples attained relevant to medical, conservation and lifestyle purposes).

UPDATE! November 9, 2017

Just as we posted this blog post on Nov 7th, a contract ecologist working for the Living Bog, George Smith of Blackthorn Ecology, just happened to be on Carrowbehy Bog undertaking some additional survey work. He had just come across a section of cut-over bog when he came upon a series of ridges, or lazy beds.

Lazy beds at Carrowbehy Bog SAC, photographed during survey work by George Smith, Blackthorn Ecology.

George says the series of ridges certainly seemed to be hand-dug, and were not the result of a machine on the bog. Peat extraction by machine did happen at Carrowbehy Bog SAC in the past, but it has been some time since machines were on the bog, and the presence of lichens and hummocks suggest these ridges have been there for some time.

George posted his pic to Twitter saying: “Lazy beds on cutover bog at the edge of Carrowbehy Bog. How desperate people must have been!”

Lazy beds on cutover bog at the edge of Carrowbehy Bog. How desperate people must have been! pic.twitter.com/upgetLxjPk

— Blackthorn Ecology (@BlackthornEcol) November 7, 2017

Are these the evidence of the ‘spuds on the bog’ experiment? Or did locals learn from it and attempt to grow their own spuds on the bog?

We’ll post an update soon….

-

MUSIC AND MYSTERY

When Seamus Kenny was collating the history and some stories for the Erritt Lodge book a couple of years ago, more stories emanated or in some cases some ‘heresay’ and rumours became more real after book completion!

As an example, more information on the French/Blake families in the district and the utilisation of Erritt Lodge for Feiseanna (Feis) in the early 20th century. Not alone was Jim Coffey and ‘Count’ John McCormack reputed to have visited the the Lodge, others such as acclaimed songwriter and performer Cathal McGarvey (Gaelic revivalist and writer of the ‘Star of the County Down’) is recorded to have performed at Erritt Lodge. Even more interesting is that a record exists of a photographer visiting a successful Feis at Erritt Lodge in the summer of 1907 and taking pictures with his Kodak camera!

Seamus also found details about the ‘White lady of the lake’… Keep checking into the website here for an update…

Garriskil Bog is the best-preserved piece of a once huge raised bog system of river floodplain bogs which developed where the River Inny enters and leaves Lough Derravarragh, not too far from the town of Mullingar. Most of these bogs are now affected by human interference, with many of them industrially harvested or strip-mined, which makes Garriskill an exceptional and all-too-rare reminder of a once common landscape in this part of the country.

Garriskil Bog SAC is the (relatively) intact bog left of centre in this Bing Maps view of this part of North Westmeath

The bog was purchased by the Dept of Finance in 1989 alongside Ballykenny/Fisherstown Bog. At the time, they bought 203 hectares between the two sites, and also purchased 506 hectares of blanket bog at the Sally Gap. Speaking in Dail Éireann in 1990, then Finance Minister Albert Reynolds (who hailed from nearby Longford) said the government had a raised bog conservation target of 10,000 hectares.

Turf-cutting on this raised bog can be traced back to long before the first records of 1840, and locals recounted stories of turf being brought to Mullingar railway station for distribution to the hospital in Mullingar – most likely St Loman’s Psychiatric Hospital. How did they bring the turf by rail? Well, the answer lies with one of Ireland’s most unique train stations…

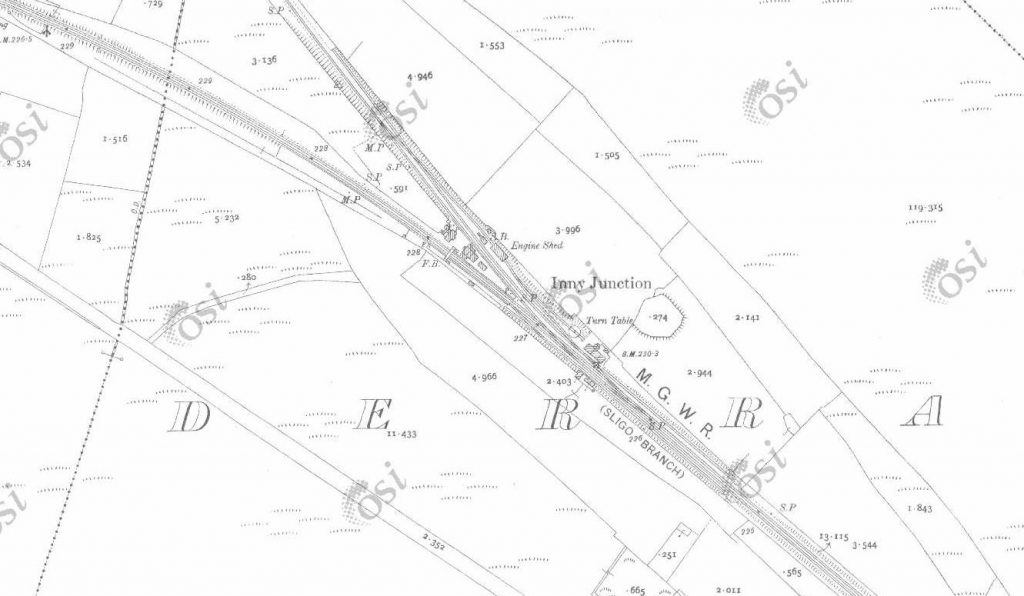

Inny Junction – Ireland’s bog train station with no roads

Right beside Garriskil Bog is the site of Inny Junction train station which, at one stage, was famously the only train station in Ireland and the entire British Isles not be serviced by a road! (this startling fact was once the subject of a question on TV’s ‘Mastermind’). With the nearest towns and villages a few miles away, it was literally in the middle of nowhere! The station was where the Sligo – Dublin line split into a Mullingar – Cavan branch.

Much of the bog to the north is bordered Dublin-Sligo railway line, which used to be known locally as ‘the Principle Line’. If you’re ever on the train from Dublin to Sligo (or vice versa) today you can’t miss the bog. If heading towards Sligo, it is just a few miles outside Mullingar after you pass Lough Owel, and if heading to Dublin it is halfway between Edgeworthstown and Mullingar. As of late 2017, 20 passenger trains daily pass through the bog, bringing thousands of people from east to west and vice-versa. This makes Garriskil perhaps the most viewed bog in the country! The full extent of Garriskil Bog is visible from one side of the train, with turf cutting and harvesting on the other side.

A Sligo-Dublin train cutting through Garriskil Bog SAC, just outside Mullingar. Photo by Living Bog ecologist John Derwin.

In modern times, it is a view that has intrigued many a train passenger. In days gone by, the sight of the bog meant a stop, sometimes a changeover, but always a chance to breathe in air that was just different to the air elsewhere – a combination of the bog and the lake made this part of the world special. With three lakes in the vicinity of the bog, there was something magical and misty about this part of the midlands.

Long before the car became the preferred mode of transport and when emigration was rife, the Inny Junction a place where many midlanders took their last breath of healthy midlands air, and their last long look at a midlands bog.

The station was built by the famous Irish railway engineer William Dargan as part of the extension of the Midland Great Western Railway from Mullingar to Longford in 1855 and opened a year later. It served people not just from the nearby Streete area, but provided rail connections for many rail users to Longford, Sligo, Mullingar, Dublin and Cavan through to Belfast.

The branch ran along an ‘island’ of mineral soil that spiked through sparse bogland country to connect with the Great Northern at Cavan giving an inland, midlands link to Belfast and the six counties.

Garriskil Bog SAC from the air, with the Sligo-Dublin rail line running alongside, and veering off to the left close to the top of the bog. You can see where the Cavan- line veered off to the right above the harvested bog, and you can also note how the track was laid on non-bog mineral ground. The River Inny runs to the left of the picture. Pic: NPWS

Traffic levels became limited and it is recorded by rail enthusiasts (including www.eiretrains.com) that the station was closed by the Great Southern Railway in 1931. From then on junction was remotely controlled from Multyfarnham signal cabin further south. The Cavan line lost its passenger services in 1947 and the GNR closed the Cavan link in 1957. The line remained in use until 1960, when it was finally closed to goods. It was later taken up, and the station dismantled. The last train to run there trundled along in late 1960, and was captured by photographers and a TV crew.

The location of Inny Junction station (1800’s) just before the line splits south for Longford and north for Cavan, with Garriskil bog running up to the Y junction

Local rumours would have it that Michael Collins often used this line when on the run during the War of Independence to visit his girlfriend Kitty Kiernan in Granard, preferring to head deep into rural Longford through rural Westmeath instead of a more direct route via Longford.

It is a place which has popped up in literature. In the book ‘Adlestrop Revisited’ by Anne Harvey, the famous English poem ‘Adlestrop’ by Edward Thomas is investigated in full, and the Inny Junction crops up when the author talks about great Irish train journeys written about by Bradshaw in 1885.

“Stops to take up at Inny Junction Halt on Thursdays and Saturdays. What romance there is in the name! For Inny Junction is a station lost in an Irish bog in the middle of Westmeath: there’s no road to it, nothing but miles of meadowsweet and bog myrtle and here and there the green patch and white speck of a distant Irish smallholding, and the silence is livened only by rumblings of distant turf carts and the hiss of a waiting Great Sothern engine on Thursdays and Saturdays.”

Michael Harding, Author and Playwright, pictured at the Irish Medical Writers Sprint Meeting. Picture: Brendan Lyon/ImageBureau

The noted Irish writer and playwright Michael Harding also referred to Inny Junction in his works. In a moving column ‘The perfect summers of my mother’s life’ in the Irish Times in 2012 he wrote about his mother, who was in a nursing home in Mullingar at the time.

“There is something heroic about her solitude now, in sleep, because she is the last of eight children, who all used to go on holidays to Westmeath. A train took them from Cavan station, and a pony and trap completed the journey from Inny Junction to the square in Castlepollard.”

There isn’t much left of Inny Junction station today, although the formation of the former junction can still be clearly seen beside the bog, and the path the Cavan line took is evident at a level crossing on the line, with wasteground where buildings once stood. The line itself is still mapped out thanks to localised tree growth over the past 50/60 years, though sleepers, rails etc are long gone. Also gone is any trace of the station building, bar the ruins of one supporting wall. The platform was the last thing to go, taken up in the early 2000’s and replaced by a wooden fence. Some platform slabs remain today, hidden among vegetation growing behind the wooden fence.

Inny Junction Train Station, Summer 2017. Nothing remains, but a few blocks among the vegetation to the right of frame.

A little further up the old Cavan line is the remains of Float Station. The name here was derived from a barge crossing two miles east on the River Inny. The Float station was part of the 26 mile Cavan branch that left the MGWR Mullingar – Sligo mainline and was located near Lismacaffrey.

The appealing small-scale railway station forms the centrepiece of an interesting collection of railway-related structures, including the platforms and the remains of goods sheds.

There is no trace of the line until you get a few miles away from the bog, at Lismacaffry (on the R395 between Lisryan and Coole).

The Earl of Granard, George Forbes, had a small private station built near his home, Clonhugh House where he enjoyed the luxury of having trains stop on request. It closed in 1947 but the platform and station house, now a private residence, are still there.

The Inny Junction story forms part of the industrial heritage of Westmeath and is an interesting historical reminder of great age of railway construction during the mid-to-late nineteenth-century.

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN – IS THE BOSS A BOGMAN?

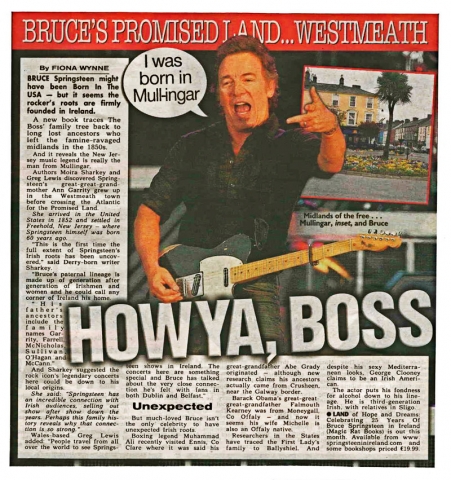

According to the authors of the book ‘Land of Hope and Dreams: Celebrating 25 Years of Bruce Springsteen in Ireland’ the entertainer Bruce Springsteen, aka ‘The Boss’, can be traced to the Westmeath village of Rathowen where the legendary rocker’s ancestor Ann Garrity (American spelling of Geraty or Geraghty) was baptised. Land records show the family cut turf in the area.

Later records show that she moved down the road to live in Mullingar before emigrating to America during the famine years and made her home on Leopold Street in New Jersey where her superstar great, great grandson was born some 70 years later.

Writers Moira Sharkey and Greg Lewis found American records which showed that Ann Garrity’s occupation was given as ‘washer woman’, but is unknown what she did before she left Mullingar.

Moira Sharkey was able to trace Ann to Rathowen using parish records. Anne Geraty (Garrity) was baptised in St. Mary’s Church, Rathowen on October 14 1836. Her parents Peter and Anne (nee Kiernan), farmed a small holding in the townland of Loughanstown on the edge of Rathowen. However, the last of Anne’s family in Rathowen died in the early 1950s.

Anne Geraty married John Fitzgibbons and settled in New Jersey. John tragically died in 1872 leaving her with six children. She subsequently remarried to Patrick Farrell and together the couple had twin daughters, Amelia and Jennie.

The latter went on to marry John McNicholas and they had three daughters, one of whom was called Alice – Bruce Springsteen’s grandmother. Alice married a local New Jersey boy named Fred Springsteen, and in 1949 their son Douglas became father to one of the greatest music legends the world has ever known. Anne Geraty passed away on October 3 1923.

The Boss was invited to visit Rathowen in 2012 when he played a number of Irish sports stadia. The Rathowen Bruce Springsteen Committee was set up to try and entice the singer to his ancestral home. However, he did not make a public appearance in the Parish. The story of his roots, however, went global! Hopefully one day, Bruce will return to Westmeath to embrace his inner bogman!

FROM THE ‘STREETE’ TO THE SUN

In 1837, Streete was described as “an inconsiderable village” during the course of a survey by John O’Donovan for the Ordinance Survey. However, there is a lot to the little village named after the ancient Breacraigne (trout people) tribe – ‘Sraid Maighne Breacraigne.’ The Breacaigh were heavily defeated and subdued by the warriors of Cairbre-Gabhra in 751a.d.

Traces of Mesolithic settlement have been found in the area, in bogland along the Inny and on the shorelines of Derravaragh, Lough Kinale.

Christianity reached here in the 5th Century and local tradition holds that Saint Patrick himself crossed the River Inny and established a church in Streete – claimed to be the first church in the Diocese of Ardagh.

If the historians are correct St. Patrick may have crossed the river at a number of points. It is said he may well have forded the river Inny where the bridge is now on the way to Streete from Coole. There is also strong talk of Patrick crossing ‘between the bogs’, which would lead you to Garriskil as there is a site of a fording point just below Garriskil Bog on the Inny. A Castle, motte and bailey are also here, marked on the 1837 OS Map as a ‘moat’ and ‘Ballyharney Fort’. The steep flat-topped mound was enclosed by a 5m wide fosse but it has been damaged. The remains of what was a ford the small square field and other indicators point to it being a significant point in the past. One has to wonder if St Patrick visited the bog at Garriskil, as he crossed either

A number of high profile Bishops, and even a Saint (St. Fintan) are all said to be buried near to Garriskil Bog.

St Fintan’s Well is at Kilfintan, and masses were celebrated there until 1770. When the coast was clear, they started again in 1905. St Fintan’s Well is said to have certain cures… Also nearly is Tobber Needle, or Well of Needle, which is said to be enchanted.

In the 1800’s Daramona House in Streete became a site of enormous astronomical significance when William Wilson, one of the leading 19th century astronomers, build a refractor then a large observatory and laboratory. Among his many achievements he carried out the first accurate measurements of the suns temperature, the radiation from sun spots and the first electrical measurement of starlight. His work was carried on by his nephew Kenneth Edward.

William Butler Yates stayed at Kildevin House in Streete many times. It is also said that Michael Collins visited the village a number of times whilst making his way to Granard to vist Kitty Kiernan. It is said he preferred to take a more ‘scenic route’ to Granard than getting off the train at Edgeworthstown. The Big Fella’s Longford connections are written about in this Longford Leader piece.

MONUMENTS

Cappagh Standing Stone

Situated four fields south of the bog, and located just off the N4 after the village of Ballinalack is a standing stone set within a ringfort. There is a neighbouring bog 250m to the west and a further ringfort 400m to NW. The tall slender limestone standing stone (approx. H 2.1m) is in the SW quadrant of ringfort (WM006-043—). Rectangular in plan and tapering towards the top with some spalling and splitting of the surface due to weathering. The stone has been reused as a scratching post. There is vague traces of two concentric slightly grooved or pecked circles on the east face, and socket stones visible at base. The entrance to the fort was believed to be on the east.

There are remnants of a number of tree rings and other ring forts in the general area, suggesting this bank of the Inny heading towards Russagh and Barratogher was of great importance. As you head up the modern road from St Mary’s Church in Rathowen here is a castle on a former moated site close to the graveyard and another moated castle called ‘castlekid’ across the road from it. Both would have been fed by the River Riffey. Along the same water course, just before the railway crossing there is a 1612 water mill built on the site of a medieval mill.