The history of Sharavogue Bog is long and varied taking in the Ice Age, peat extraction, famine, rail disasters and much more besides, but it is the 1990’s intervention of two local farmers, Mr Liam Egan and Mr Patrick Headon, after drainage channels were sliced across the high bog which has ensured Sharavogue will remain as a living bog for the enjoyment of generations to come. In fact, the most recent episode in its history is probably the most important.

The efforts made by Mssrs Egan and Headon in preserving the bog in the 1990’s have been internationally recognised, as the following 1998 report from the Irish Times illustrates:

Offaly farmers win award for saving raised bog

“A major conservation award has been presented to two farmers from Birr, Co Offaly, for saving a raised bog at Sharavogue at Ballyegan.

Mr Liam Egan and his neighbour, Mr Patrick Headon, were recently given a special award by the Dutch Foundation for Conservation of Irish Bogs, in the Netherlands.

Sharavogue Bog is one of the best remaining examples of raised bog in Ireland as it contains pristine high bog but also preserves important relics of the original lagg-zone: the transition zone between bog and the surrounding landscape.

Such lagg-zones are extremely rare in the Irish and international context as they were lost in virtually every remaining bog site as a result of marginal drainage and peat cutting.

Because of this Sharavogue is listed as a Scientific Area of Conservation under the EU Habitat’s directive.

This week, Mr Egan, who is very active in the Irish Farmers’ Association and is chairman of its animal health committee, said he was delighted with the award.

The bog came under threat some years ago when an effort was made to develop it for peat extraction, he explained, adding that he and his neighbour, Mr Headon, a stud farm owner, took out an injunction against the developer to stop the drainage and destruction of the site.

“We began a search and found the original owner of the bog in England, a descendant of the local landowner, and we purchased the bog from him. We were then sued by the developer for loss of earnings and it dragged on for years and cost both of us a lot of money but in the end we won out and the bog has been saved,” he said.

They later entered into a management agreement with Duchas, the heritage service, which is currently looking at repairing the bog.

“I just love the bog. I’m delighted that it has been protected and the area around saved from the exploitation of the peat with all the problems that creates,” he added.

The International Award for Nature Conservation Merit was given in recognition of an outstanding contribution to peat-land conservation.

The presentation was made at Groenveld Castle in the Netherlands by the chairman of the Foundation, Prof Matthijs Schouten, in the presence of the Irish Ambassador to the Netherlands, Mr John Swift, and representatives of Dutch and international nature conservation organisations.

The Dutch Foundation for the Conservation of Irish Bogs was set up in 1983 to give international support to peat-land conservation in Ireland.

ENDS

Source: http://www.irishtimes.com/news/offaly-farmers-win-award-for-saving-raised-bog-1.221252

1989 – YEAR ZERO FOR SHARAVOGUE

In September 1989, a High Court injunction was served on a fuel merchant to prevent the exploitation of Sharavogue Bog which had been intact up to 1988.

During three days, a long perimeter drain and 21 transverse drains were mechanically inserted into the bog. It was to be the first stage in peat development at the site. However, an injunction was taken by two local farmers, who owned some of the bog and surrounding lands.

Two-thirds of the bog had no title recorded in the Land Registry, and the fuel merchant claimed that the title belonged to him, and other land owners.

The dispute that followed was based on trespass, but it was discovered this could not be sustained – in order to have been successful in preventing any further development on land in which no title is evident, one would need to have an interest in acquiring that land. The neighbouring farmers maintained that drainage to two thirds of the bog would have irreversibly damaged the remaining one third and the callow lands they owned.

But the old law in relation to ‘percolating water’ was against the conservation case: if you were a landowner, you cannot prevent damage to underground drainage on your land from drainage initiated by a landowner on neighbouring land.

The court case was to have taken place in 1990 but it never came to court. After a long and exhaustive search, the two local farmers and their solicitor managed to discover the original title-holder of the bog. They discovered the land was being held by a person living in England, and so a trip across the Irish Sea was made.

The title-owner was sympathetic to the cause of raised bog conservation, and subsequently agreed to sell the free-hold, jointly to Mr Patrick Headon and Mr Liam Egan.

Restoration and repair work was undertaken and the new owners entered a management agreement with Duchas (now the National Parks and Wildlife Service – NPWS).

Since 1990, any peat development over 50 hectares, such as that attempted at Sharavogue, is subject to Environmental Impact Assessment and planning must be obtained. This was a significant step forward for bog conservation in Ireland as mechanical extraction of this magnitude was very different from traditional cutting, like that with a sleán, which made little impact over the centuries.

SHARAVOGUE – THE BOG BY THE RAIL LINE

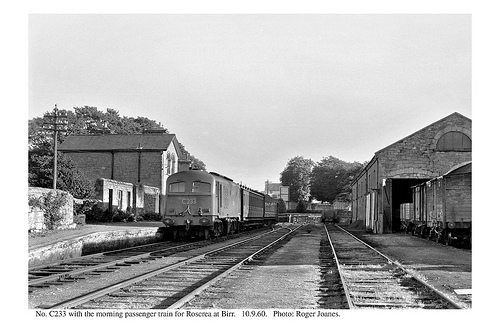

Last in line… The last train to use the Birr-Roscrea rail line which ran alongside Sharavogue Bog., pictured in 1960. Pic: Roger Jones.

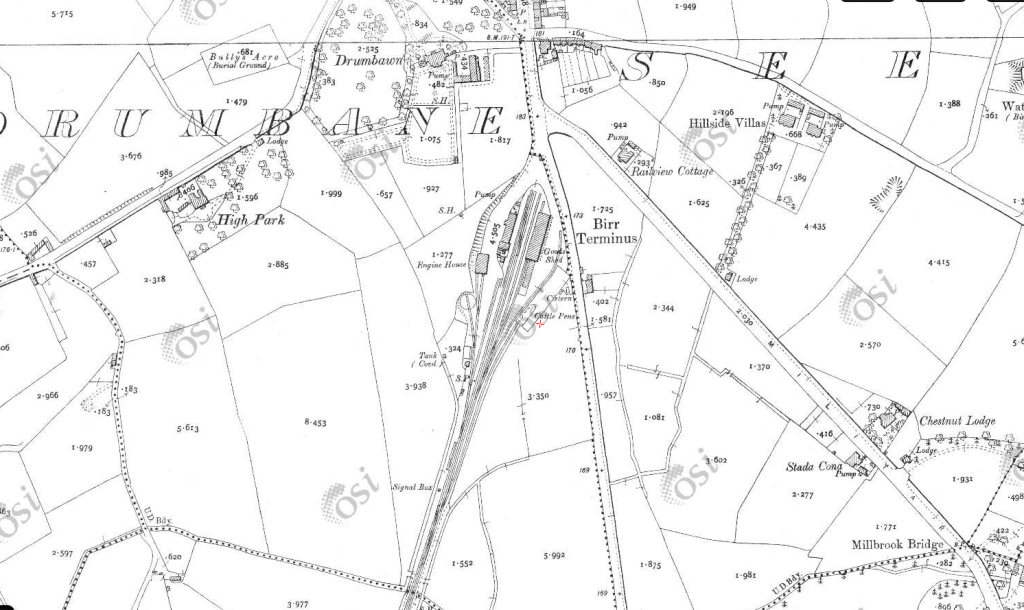

Sharavogue Bog is bordered along its eastern edge by the remains of a disused rail line, which was once the Birr to Roscrea line, a 12 mile branch which linked Birr to the Dublin and Cork lines.

A section of the line went through the outer edges of the bog giving passengers on the twice daily service a tantalising glimpse of what at the time was a pristine raised bog. Indeed, the historic 25” maps record the line running along an uncut bog, with just a small handful of facebanks marked. A siding, the Sharavogue siding, is recorded in the National Library archives. Today, the outline of the track, in perfect curved lines along the bog is all that remains, together with some ruined buildings and sidings. The pics below show the line along the top and bottom of the bog.

In recent years there have been multiple proposals that the line – and others in the area including the Birr to Portumna, Ballybrophy to Limerick and Birdhill to Ballina lines – be developed for tourism. Greenways and cycleways along disused rail-lines have increased in popularity in Ireland in recent years with the Green Way in Mayo and the Old Rail Trail in Westmeath very popular amenities with locals and visitors alike.

The history of the line is intriguing; with its origins going back to 1853 when, after pressure from Lord Ross, a line between Ballybrophy and Birr (then called Parsonstown) to link up with the Dublin to Cork line was started.

In October 1857 the stretch between Ballybrophy and Roscrea was completed, with the Roscrea to Birr line completed in March 1858. It linked Roscrea to Birr for the next 105 years, until it eventually closed in 1963. There were at least two services daily, and trains left from an elegant rail station on the outer edges of the town.

The Birr to Roscrea line brought many visitors to both towns and was used as a route to the Monastery and a number of Holy Wells. People used it to get to the Our Lady’s Well at Clybanane, the Grotto at Fanure, the Holy Well near the former Cistercian Abbey Mill and others to get to the ‘Boiling Well’. The ‘Boiling Well’ is remembered by local man George Cunningham as a warm, natural spring well which bubbled, hence the name. It is just off the old Birr Railway line about 2 kms from Roscrea and near the Moneen (tributary of the Little Brosna).

It was also used by people with fishing rods instead of rosary beads, to get to the Brosna and Perry’s Well for fishing.

Four bridges are recorded on the line, of which two still retain their spans. The skew brick arch road bridge over the railway at Sharavogue, is one of only three arched bridges in Offaly to use this material. It is close to a former siding. Some of the old outbuildings are gone, but one exists alongside the bog, and it is believed what is now a house was once a station that served Shinrone.

The line closed in 1963, one of over a dozen branches to close forever that year. The last train to use it with passengers departed from Birr Station in September 1960. Photographer Roger Jones captured that occasion:

Birr station has long since been converted to a number of private residences with the goods sheds and other outbuilding in commercial and warehousing use (see below). The railway lines are all gone here but some remain along the line…

The Runaway Train

A notable event on the Birr to Roscrea line was the Runaway train crash of 1910 which occurred on the morning of July 19, 1910 when two trains, carrying between them over 800 passengers (most of them clergy) collided close to the bog. Some divine intervention must have been at play as no one was killed, despite over 400 people being injured, many of them seriously.

The drama started when a special train left Birr station to take over 750 pilgrims to Roscrea and onto Queentown (Cobh) where they would catch a ship that would eventually bring them to Lourdes. There was a fault with the brakes, so when the train arrived in Roscrea the driver uncoupled the engine, leaving the ten carriages on the Birr platform. Due to the numbers trying to get to Lourdes, four more carriages were to be added onto the ten.

As the four extra carriages were being shunted into place, the ten coaches were jolted and suddenly they moved out of the station and gathered great speed down the incline towards Birr. The line had a long slope between Brosna and Roscrea, with trains having to climb almost 50 metres over five kilometres.

Despite frantic efforts by the head porter, Mr Deering, and the station master, Mr Hayes to apply the handbrake, the carriages ran away at speed. In the distance they could see smoke down the line…. It couldn’t be… Yes, it was another train! The 09:15 from Birr was on the way towards Roscrea.

Deering waved a red flag, and others waved their hats from the runaway train, and luckily, the driver, Tim Broughall, and fireman on the 09:15 saw the commotion and had time to stop and begin backing their train back up the line. Sensing the obvious, many passengers on each train jumped – breaking arms, legs and other limbs as they flailed from the moving carriages onto the ground below. The trains collided at Fanure, just down the line from Sharavogue Bog.

The force of the collision was severe, but thanks to the evasive actions of the 09:15 driver, not as bad as it could have been.

The impact demolished the first four carriages of the runaway train, and it was the pilgrims on these who suffered the greatest injuries. Luckily, there were some nurses and doctors on board and monks from a nearby Monastery came to help. The army from the Leinster Regiment, stationed at Crinkhill also came. It’s not known if they grabbed some sphagnum from Sharavogue en route to the bog. At the time, sphagnum moss was used extensively by the army to treat wounds on battlefields abroad…

The aftermath of the 1910 train crash on the Birr-Roscrea line. Pic with thanks to Roscrea Through The Ages Facebook page)

Sums between a crown (25p) and 20 were offered as compensation, and the 76 seriously injured took these. Eventually there were 492 claims. The driver of the 09:15, whose actions undoubtedly saved many lives, Mr Broughall, was given shares in the GSW rail company.

The Stolen Line

The Birr-Roscrea line was successful in operation, but the same cannot be said for its neighbouring line, the so-called Stolen Line.

In 1863 a line between Birr and Portumna in Galway was started and it opened five years later as P. & P. B. R. or the Parsonstown & Portumna Bridge Railway. It was difficult to build with the bog at Curraghglass particularly hard to drain. The line was losing money from the start and the company behind it quickly built up debts. It closed in 1878, and swiftly became known as the ‘stolen railway’ after backers owed money, farmers and others began to steal property.

At first, no attempt at pillage was made at the Birr end, but a few miles out the country, the ballast started to disappear. It was found to be very useful in making farm roads and roadways into bogland. Next the fishplates, spikes and other small pieces of iron started to vanish. No doubt the blacksmiths of the time were glad to receive them, and it was said that ironmongers came from all over the country to engage in an early form of recycling.

The rails went next and they were put to many uses. The sleepers were taken up and together with the rails were used for sheds and other farm buildings – and even firewood. The thieves came from far and near and worked quickly. After a few days, nothing but the bed of the railway remained.

The station house in Portumna was allegedly stripped clean and effectively demolished in one night! Many homes and outhouses were fitted with the timber, windows, doors, slates, kerbs, and paving stones.

An attempt was made to remove the girders of the six span bridge over the Little Brosna at Riverstown, but the attempt was thwarted by the local RIC.

Some marauders were brought to court, but nobody could be found to represent the company. This paved the way for a wholesale grab of what was left and practically every trace of the line and its infrastructure was looted.

Historian Joe Coleman wrote of the prevailing feelings in the immediate area in the Irish Railway Record Society: “Even today people in the area people are reluctant to talk about the P&PBR. Some will say that the whole line disappeared in a single night, others will either claim that they never heard of it, or if they have, they will blame the people of East Galway for stealing it. However, without looking in any particular direction, there is much evidence to suggest that the railway didn’t go too far away in the end.”

Useful Links:

For mere on ‘The Stolen Line’ see Seamus J King’s piece HERE and also Joe Coleman’s Irish Railway Record Society piece HERE and a New Zealand academic paper HERE

Newspaper report of Portumna – Birr- Roscrea Greenway plan

Railways Archive (including accident report)

MONUMENTS AND INTERESTING FEATURES

The nearest recorded monument to the bog is immediately to the east of the rail line at the top, northern end of the bog, where there is evidence of a large circular enclosure in the townland of Kilnalacka. According to the National Monuments Service, no surface remains visible, but the levelled monument was situated on a flat pastureland to the east of the bog. It was depicted as a large circular enclosure or platform on first two editions of the OS 6-inch maps. Later it was depicted not as an antiquity, but as a roughly oval-shaped grove of trees on the 1908 ed. OS 25-inch map.

In the townland of Rathbeg to the east of the bog (indeed, the bog is sometimes referred to as Rathbeg Bog) there lies the remains of a ringfort or rath. It is situated on high ground in an upland area. According to the National Monuments Service, the large circular area (diameter 40m) is enclosed by two earth and stone banks with intervening fosse (3m) and impressive causewayed entrance (4m) at the south west. The inner bank (Wth 2m; ext. H 0.7m) is reduced to a scarp in places and has a modern gap (3m) at its north end. There is a large quantity of stone in the better preserved outer bank (Wth 3m; ext. H 0.5m; int. H 0.75m) which may be due to field clearance debris. There is no evidence of an external fosse.

Just above this site is another enclosure in Ballyegan which is a barely discernible outline of a destroyed enclosure consisting of a circular area (diam 43m) located on flat pasture land. Depicted as large circular enclosure on 1912 edition of the OS 6-inch map.

There are further ring forts in the townlands of Ballygaddy (Clonlisk By) over the N62 and Ballincor Demesne, and Boveen. A Fulacht Fia was located in Clonkelly to the north west of the bog, in the 6-inch OS maps but has since been levelled and there is no evidence of it.

The above descriptions are derived from the published ‘Archaeological Inventory of County Offaly’ (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1997).

Holy Wells and St Patrick

The landscape all around Sharavogue Bog and between Birr and Roscrea is dotted with Holy Wells. Many are not recorded on more modern maps, but are visible from the old OSI Maps (available online HERE) and the HISTORIC VIEWER from the National Monuments Service and Department of Arst, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs.

People used it to get to the Our Lady’s Well at Clybanane/the Grotto at Fanure, the Holy Well near the former Cistercian Abbey Mill and others to get to the ‘Boiling Well’, close to Roscrea. The ‘Boiling Well’ is remembered by local man George Cunningham as a warm, natural spring well which bubbled, hence the name. It is just off the old Birr Railway line about 2 kms from Roscrea and near the Moneen (tributary of the Little Brosna).

With thanks to Offaly County Heritage Officer Amanda Pedlow and the Roscrea People we below republish an interesting article from 1975 about a local attempt to revive the Pilgrimage to Our Lady’s Well at Clybanane.

It was said that none other than St Patrick founded the well. On the death of his charioteer Odhran, near Killeigh in Offaly, St Patrick returned to the spot known as Clybanane (near Fanure) where he interred Odhran’s remains. Whilst there, he is said to have dedicated a well to the Blessed Virgin. People from all corners of Ireland would pray at the well for a safe journey, and a nearby oak tree (now gone) was adorned with religious objects. The well became known locally for many years as ‘The Well of St Patrick’s Coachman’, and some referred to it as the Grotto. Pilgrimages died out in the 1950’s, until the August 1975 revival, detailed below: