Raised bogs are among the world’s oldest living, near-natural eco-systems. Many of Ireland’s great raised bogs date back almost 10,000 years.

They are found mainly in the midlands and it is estimated that they once covered almost a million acres of land. However, today, less than 1% of that figure remains as active, living bog – Bog that can still support life.

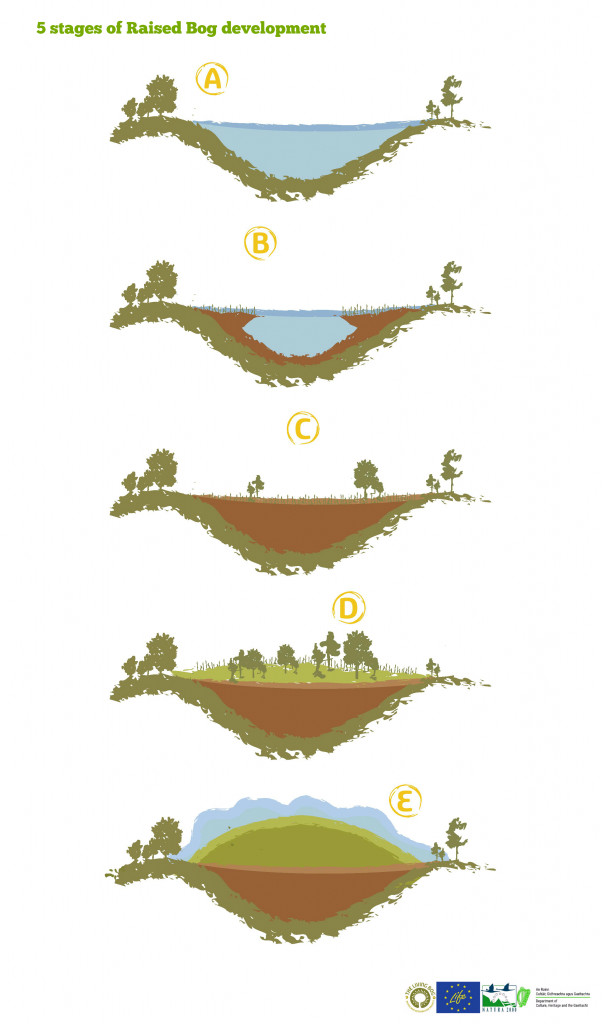

Raised bogs began to develop 10,000 years ago in depressions occupied by shallow lakes, usually left behind by retreating glaciers after the Ice Age (A.)

At the time the land was washed by nutrient-rich ground water and anaerobic conditions occurred. At first, reed beds develop but they die off, and their dead remains begin to accumulate (B.) and a Fen appears as fen peat starts to accumulate.

Rushes, sedges, grasses, herbs and wild-flowers, trees and shrubs begin to grow and die as the fen peat – dark and fibrous – accumulates. (C.)

The fen peat layer thickens so that the roots of plants growing on the surface are no longer in contact with the calcium-rich groundwater. The only source of minerals for plants is now rainwater, which is very poor in minerals (D.)

Raised bog species, such as Sphagnum mosses begin to invade and eventually the fen becomes a raised bog. The Sphagnum mosses can survive on mineral-poor rainwater alone and the spongy-peat which forms over the fen is above the influence of ground water. The fen plants are replaced completely by plants which can survive in the much poorer, acidic conditions and as the mkosses accumulate and plants die, a raised bog is born (E.). the flattened dome of a raised bog is slightly higher than the surrounding countryside, hence the name.

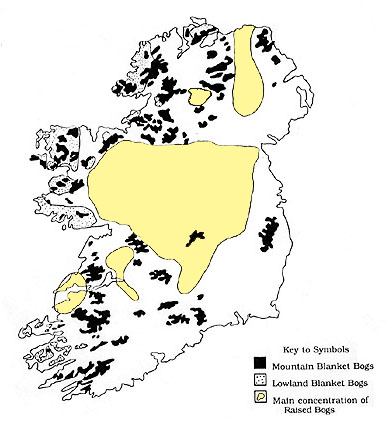

Raised bogs occurred mostly in the midland counties of Offaly, Westmeath, Longford, Laois, Roscommon and Tipperary, Kildare and the western counties of Galway and East Mayo. they were also found in the Bann Valley in Northern Ireland.

In 1979, Hammond estimated that Raised Bogs had covered 310,000 hectares (750,000 acres) in the early to mid 1800’s. Today, less than 8% of that figure can be deemed suitable for restoration, with 37% lost since the early 1990’s. Today we have less than 1% that can be deemed active, living bog, and most of this is held within 53 SAC/Natura 200 sites.

Waterworks

Drainage is much better on the steep margins, which are rather dry and largely covered in ling heather. Most bog margins in Ireland have been cut away, particularly by machine since the 1970’s, and the cutting causes the peat to dry out and shrink, resulting in the formation of dangerous, deep cracks.

Originally there would have been a narrow band of fen around the edge, where there was influence from ground water, but drainage and cutting has largely removed this feature. It is exceedingly rare today.

Away from the margins, the bog becomes wetter and the Sphagnum mosses dominate – there are over 20 types but usually four or five are very common. Some form hummocks (which can grow to a metre high and be capped by heathers and different mosses) while other are found in hollows and pools. There is great variation in their colours – green, orange, red and brown – with some taking on different hues in Autumn and Winter, mainly variations of red. Together with dying plants and cotton grasses they have rise to the name ‘red bogs’. In the wetter parts, white-beaked sedge, bog asphodel, cotton grasses and other rare plants grow, with bog beans and bladderworts growing in pools. Bog rosemary and cranberry, with its bright red, sharp-tasting berries are found creeping through Sphagnum carpets and sundews too dominate all around. Lichens – Ireland’s own Coral Reef – occur in patches. Despite raised bogs not being very hospitable places, hundreds of bog specific plants and animals flourish.