Local And Community

GET IN TOUCH

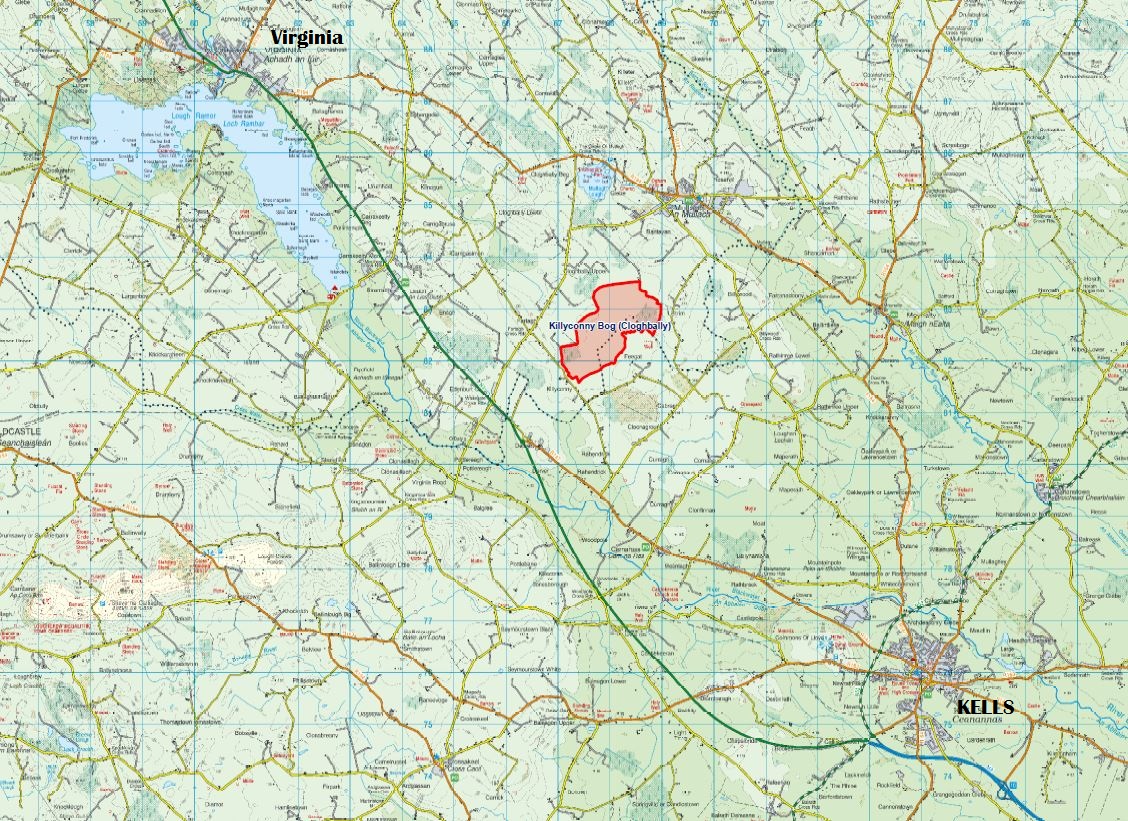

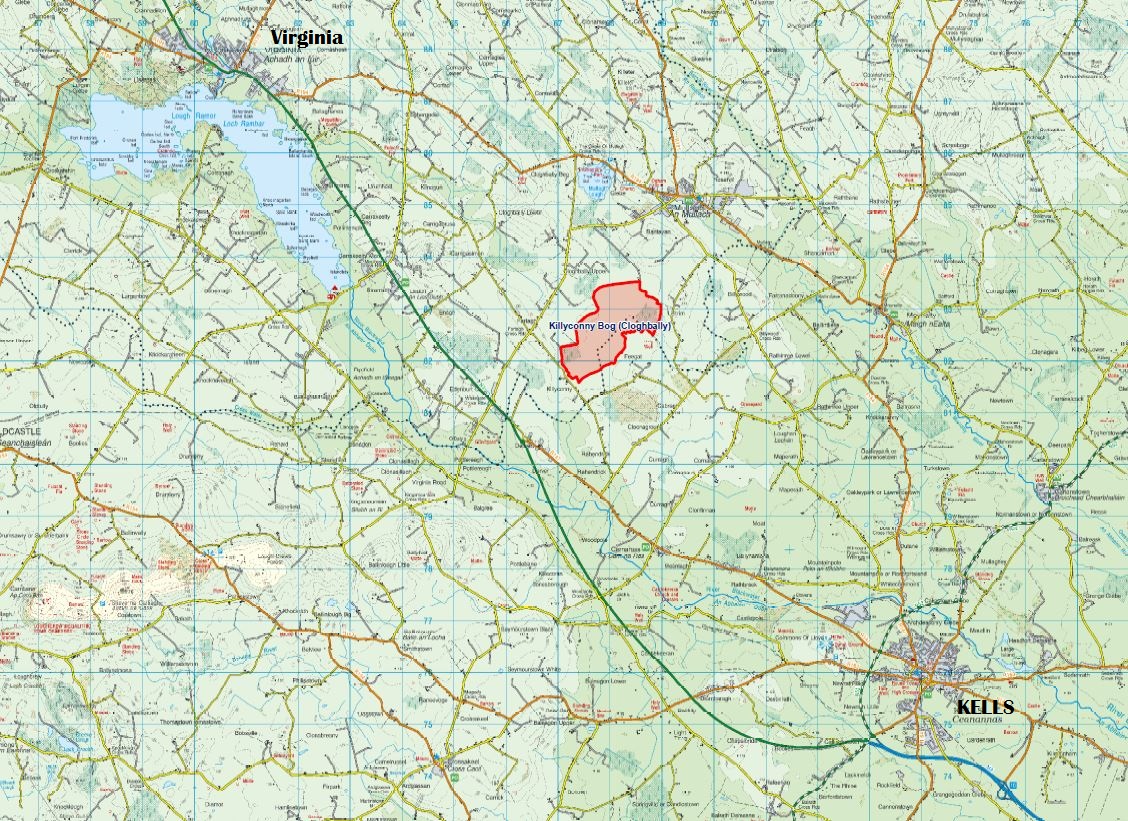

This page belongs to the communities surrounding Killyconny Bog SAC and the town of Mullagh. Whether you are a local heritage group, a men’s shed, a sporting organisation, a tourism and development association, a charity group or even just an individual with something interesting to put out, this section of the Killyconny site is for you.

Stories and history from the area is currently being compiled by our Public Awareness Manager, Ronan Casey. If you have any interesting stories, photos, information or anything concerning the bog or the surrounding areas, please email ronan.casey@npws.gov.ie or call him on 076 1002627.

If you have a community web presence, or newsletter or information sheet you’d like to see reach a wider audience, don’t hesitate to let Ronan know and it will go up on this site.

We will also link to interesting people and events in the areas surrounding this important raised bog. We want to celebrate the past, present and future of this area.

The culture and traditions associated with bogs in Cavan, Meath and the North-East deserve to reach a wider audience and our Public Awareness Manager is keen for this aspect of our bogs to be celebrated just as much as the conservation and restoration of raised bogs.

Please note that by publishing any articles, or sharing details of events etc ‘The Living Bog’ (LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032), DAHRRGA, and EU LIFE are not endorsing them. Merely we are opening a forum to the local community. The views expressed will not necessarily be those of LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032 or any other body associated with it.

Mullagh Bog: An oasis for now and a resource for the future*

By Jim Smyth, Rantavan, Mullagh – Originally published in the ANGLO CELT newspaper in 1997.

Mullagh Bog started forming about 10,000 years ago after the last Ice Age. As the climate became warmer the one to one-and-a-half mile ice sheet began to melt leaving behind in the landscape debris of soil, pebbles and boulders. Large mounds of this debris formed into what today we call drumlins and between many of these badly drained hills, lakes formed in the hollows. As the ice retreated northwards it left the classic drumlin shape – sharp on one side and drawn out on the other in the direction of the retreating ice. Numbering thousands, the drumlins gave rise to the so-called ‘basket of eggs’ topography.

Large boulders called erratics can still be seen throughout the drumlins. Marks or scratches on these boulders sometimes give an indication of the direction of the ice. Often, these non-local boulders were used by man in the construction of his sacred monuments, in fortifications, or as markers for burials.

After the melting of the ice a large shallow lake was created, e.g. as at Mullagh/Killyconny/Cloughbally Bog as we know it today. The climate then being moist and cool favoured the development of vegetation, forming fen and as it became more solid – bog. The moistness ensured a plentiful supply of water for its continued growth and the cool temperature limited the rate of evaporation.

The ground floor of the lake would have formed a chalk-like marl because of the poor drainage andf would also help hold the water. The three ingredients that favour bog growth are: The extent of rainfall; The low temperature which reduced evaporation; And the soil which restricts the drainage. Under these waterlogged conditions dead plants along the edge of the lake do not fully decompose and they begin to form a peat and to act as an anchor for further plant growth and over hundreds of years this accumulates and reduces the size of the lake progressing from lake to fen to raised bog.

The dominant plant that grows on the surface is called ~Sphagnum Moss. The moss is very important in the formation of the bog because it acts as a huge sponge drawing up the water with it as it grows.

During the long history of its growth, the temperature remained almost steady. However, about 4,500 years ago the annual rainfall decreased. This caused the bog to dry out to some extent and allowed the invasion and establishment of a pine forest. This forest survived for some 500 years until the climate became wetter again. The bog recommenced growing and the surface became wetter and the trees and vegetation died. The moss took over and these plants became buried. From time to time pine tree trunks are uncovered by turf cutters.

The area of raised bog at Mullagh covered approximately 1000 acres. It is confined to the shallow basin of the former lake. It will not grow beyond this point as the amount of rainfall that it receives limits its further spread. If it were in the West of Ireland with its higher rainfall and moist climate, then the Sphagnum moss could continue to grow over the landscape and it might become a blanket bog.

Seeing that such a high percentage of Mullagh bog is still in its virgin state is unusual in Ireland and Europe. It appears that over the years, with traditional turf cutting, that the bog grew enough each year to compensate for the removal of fuel for local consumption. However, this situation has changed dramatically for the worst in recent years with the arrival of mechanised turf cutting equipment and the drainage of the bog.

The sponge is becoming drier with each passing year. In our locality the bog acts as a massive sponge. In times of flood the bog is a major outlet in soaking up the water and preventing massive flooding. In times of drought the bog gives up its water to the local area. Therefore, a well working bog acts as a buffer between the local community and drought and flood. If the bog is to be allowed to be drained indiscriminately then the level of water in Mullagh Lake may fall and this too has implications for everybody, the lake being the town’s water supply and the overflow being a valuable water source for cattle.

Recently, a preservation order was placed on a large section of the bog and we not need to begin to realise the valuable resource and friend this bog was and can be for the people of the community now and into the future.

With more road networks being planned, opening up the countryside to industry and housing estates to follow, it is all the more important to preserve out boglands to support our water levels to meet our future needs.

Bogs themselves are very interesting places. At first, raised bogs appear to be dull, flat and lifeless. But by taking a closer look one discovers a rich wonderland of flora and fauna. It is one of the last retreats of our indigenous wildlife and many of our rare plants and herbs. A lot of this wonderful diversity was destroyed the last time the bog was burned. Hopefully through increased understanding this disaster will never happen again. Since the burning a lot of the fauna is at infant stage, and a wide variety of plants are repopulating the high bank. There are many different species of Sphagnum Moss growing, adding to the variety of colour. The bog is a safe roosting area for wildlife to breed and the heather provides extra protection.

Bogs have great preserving powers due to the lack of oxygen. Many articles and ancient objects have been uncovered in bogs. They have also been used to store butter and meat to keep it fresh and cool. Human remains have also been found in a well preserved condition after hundreds and thousands of years.

Turf

The main use of the bog at Mullagh has been the production of turf for use in the home. To walk on the centre of the bog it is very wet and springy, which is its healthy state. Along the perimeter it has dried out considerably and is encroaching on the centre of the bog, though it has still the traditional humped back profile of the traditional raised bog. In fact the bog is almost all water, as high as 95%, but when it is cut into sods and exposed to the sun and wind it contracts and becomes hard and dry and makes the ideal domestic fuel.

When making turf the top layer of peat or scraw is removed as it is unsuitable for fuel, but was a great insulator of heat in thatched houses. Having removed the scraw a special spade with a wing on the surface is used to cut the turf. The sods are then laid out to dry on the bog surface. This special spade is called a ‘shlane’. When the turf has become sufficiently dry on the low bank it is then stacked in reeks. The saving of the turf in years gone by lasted well into the Autumn. With modern machinery the rearing period is much shorter.

No major threat existed to the bog, until today with the arrival of modern machinery. The bog is not ours to destroy. Its survival may be an essential part of the independence between man and landscape. Kill one and the others suffer. Before large scale drainage took place, the bog would have contained 90-95% water, but today it is much less and the bog is dying. In order to ensure its survival and continued growth these drains will have to be closed off. Neighbouring farmers will have to be consulted on this matter to encourage co-operation rather than confrontation.

The future

Ireland is the most westerly country in Europe. Most of the peatlands on mainland Europe are now extinct. To conserve our bog it must be seen in this broader European context. We are fortunate enough to have a substantial raised bog in our Parish that is suitable for conservation and exploitation. Many other European countries have cut away all of their bogs and are now artificially trying to recreate bog growth conditions at enormous expense. They now regret not having the foresight to conserve some of their living bogs. For this reason they are keen to get involved in helping Irish people to preserve their boglands. The Dutch Foundation was set up in 1983 to raise money and to protect endangered bogs.

Financial incentives are available to farmers to preserve their banks on the bog under the REPS programme. Bogs are reckoned to be ten times greater at purifying the atmosphere than the rainforests.

Because of the diversity of habitat both on the bog surface and the surrounding area, they could become very interesting from an educational and tourist point of view, especially for school projects. The raised bog could be used for teaching Biology, Ecology, Chemistry, History, Geography and Folklore. It could also be used by photographers and ornithologists and observers of wildlife through the building of hides for observation.

The Irish Peatland Preservation Council are engaged in a campaign lobbying the government, promoting public awareness and education. The campaign is focused towards conservation of raised bogs as the threat of extinction to this unique habitat is now a reality. However, conservation should not be seen as an activity of a select committee, but part of an overall plan bringing benefits to the whole community. It is in everybody’s interests to preserve the bog and try and improve on its present state. The time for conservation is now. We must realise the treasure we have in our landscape and its wildlife. It would be intolerable to allow the unchecked destruction of an Irish landscape feature without making an effort to ensure that it is conserved for our future generations.

Conclusion

We have seen from the above how important it is to ensure the healthy functioning of the bog as a water regulator and as an oasis for wildlife, plants and herbs. We have also seen that the bog and its different systems could also be used as an educational tool for various levels of students in the parish and from outside, maybe we could look into getting some Masters and Doctorates compiled on our bog. We have also seen that this could become a tourist attraction for Irish and Foreign watchers and photographers of birds, wildlife and flora. It can also be seen as a way of recreating the story of the bog and the people who lived there and the way they managed from day to day.

It would be a pity to pass through a lifetime without making a positive contribution to the well-being of our environment.

Many other communities like ourselves have been surrounded by what for Europeans and Academics was a unique place and the community never realised it. We now know that we have a resource of potential, to find out its true extant we need to get a Resource Audit of the bog, an estimation of its current health and then what it would take to conserve it and to sensitively exploit its educational, cultural and tourism potential. Then, as a community, we could decide how we would manage this friend in our midst.

Jim Smith, Rantavan, Mullagh, Co Cavan.

*DISCLAIMER: The above article is the full version of an article submitted by local Mullagh man Jim Smith to a number of bodies and journals in 1997. We are happy to republish it on ‘The Living Bog’ website. Please note that republishing is not an endorsement of the article. Views and points made in the above article are not those of the ‘The Living Bog’ LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032 or that of DAHRRGA or EU LIFE. This article appeared in an edited form in the Anglo Celt newspaper in 1997:

MULLAGH BOG – AND WHY WE SHOULD PRESERVE IT

The area of Mullagh that can be classified as a raised bog covers an area of approximately 1000 acres. If present levels of production are allowed to continue unchecked, within a few years we will have nothing worth preserving. Many bogs are now faced with the threat of extinction. Do we want the same thing to happen to our fine example of a raised bog? Once lost, they cannot be replaced. Now is the time to realise the threat and act responsibly. There are a number of reasons why it is so important to preserve our raised bog.

The dominant plant on the bog is Sphagnum Moss. There are different species of this moss on the bog, adding to the variety of colour. Because of drainage, a wide area along the perimeter of the high bank is much drier than further inland and therefore has not as good a population of plants further inland.

To have a raised bog in one’s area is a huge asset from various points of view. The bog probably dates back 10,000 years and because of the way it has grown in that time a lot of important information is preserved there. Samples of bog oak can be seen in old houses used over windows and doors. Our bog acts as a massive sponge in our locality. In times of flood the bog is a major outlet and in times of drought it is a huge reservoir. The bog can help control water levels in river catchments. If the bog is allowed to drain then the level of water in Mullagh Lake may fall and that has implications for everybody – the lake being the town’s water supply and the overflow being a valuable water source for cattle.

Because of the diversity of the habitat both on the bog surface and in the surrounding area, they could become very interesting from an educational point of view, especially for school projects. The raised bog could be used for teaching biology, ecology, chemistry, history, geography and folklore. Conserving our bog must be seen in the European context. Most of the peatlands on mainland Europe are almost extinct. We are fortunate to have a substantial raised bog in our Parish that is suitable for conservation. Many other EU countries have cut away all of their bogs and are now trying to artificially recreate bog conditions at enormous expense. They now regret not having had the foresight to conserve some of their living bogs. For this reason they are keen to get involved in helping Irish people to preserve their boglands. The Dutch Foundation was set up in 1983 to raised money and to protect endangered bogs.

The Irish Peatland Preservation Council are engaged in a campaign lobbying the government, promoting public awareness and education. The campaign is focused towards conservation of raised bogs as the threat of extinction to this unique habitat is now a reality. However, conservation should not be seen as an activity of a select committee, but part of an overall plan. It is in everybody’s best interests to preserve the bog, and try and improve on its present state. Raised bogs are becoming huge growth areas from a tourism point of view. Farmers who joined the REPS scheme are entitled to an extra 20% premium if they preserve their bog attached to their farm.

A more detailed survey (of Mullagh Bog) would need to be carried out to assess its importance from all points of view. The cost of the survey is £1,000.

Jim Smith, Rantavan, Mullagh, Co Cavan.

*DISCLAIMER: We are happy to re-publish this letter, which is by local Mullagh man Jim Smith and which was written in 1997. The view and points made in the above article are not those of the ‘The Living Bog’ LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032 or that of DAHRRGA or EU LIFE and are those of the author.