History of Ferbane Bog

MARY WARD and FERBANE BOG

Mary Ward was born Mary King in Ballylin near present-day Ferbane, on 27 April 1827, the youngest child of the Reverend Henry King and his wife Harriette. She and her sisters were educated at home, as were most girls at the time. However, her education was slightly different from the norm because she was of a renowned scientific family. She was interested in nature from an early age, and by the time she was three years old she was collecting insects, most of them out on Ferbane Bog!

Mary Ward

Ward also drew insects, and the astronomer James South observed her doing so one day. She was using a magnifying glass to see the tiny details, and her drawing so impressed him that he immediately persuaded her father to buy her a microscope. This was the beginning of a lifelong passion. She began to read everything she could find about microscopy, and taught herself until she had an expert knowledge. She made her own slides from slivers of ivory, as glass was difficult to obtain, and prepared her own specimens. The physicist David Brewster asked her to make his microscope specimens, and used her drawings in many of his books and articles.

Shockingly, at the time, Universities and most societies would not accept women, but Ward obtained information any way she could. She wrote frequently to scientists, asking them about papers they had published. During 1848, Parsons was made president of the Royal Society, and visits to his London home meant that she met many scientists.[4]

She was one of only three women on the mailing list for the Royal Astronomical Society (the others were Queen Victoria and Mary Somerville.

She illustrated her six books and articles herself, as well as many books and papers by other scientists.

She was a pre-eminent scientist, and it is a miracle that Ferbane Bog, in the shadow of a turf burning power station, survived at all. it is the site where she made many of her discoveries, and we hope to encourage young scientists to follow in her trail-blazing footsteps.

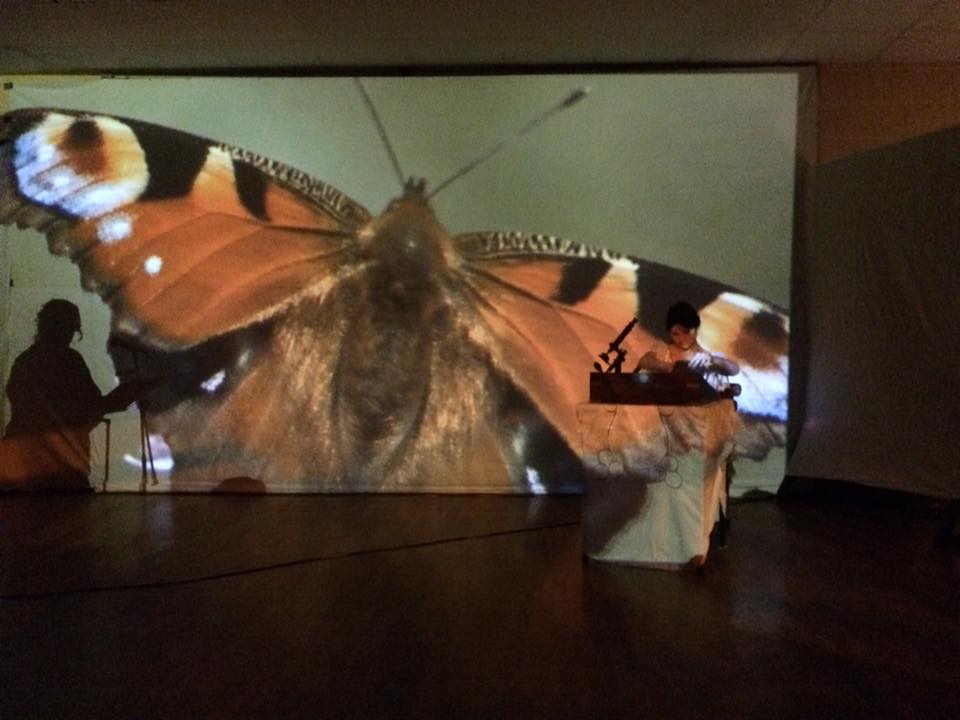

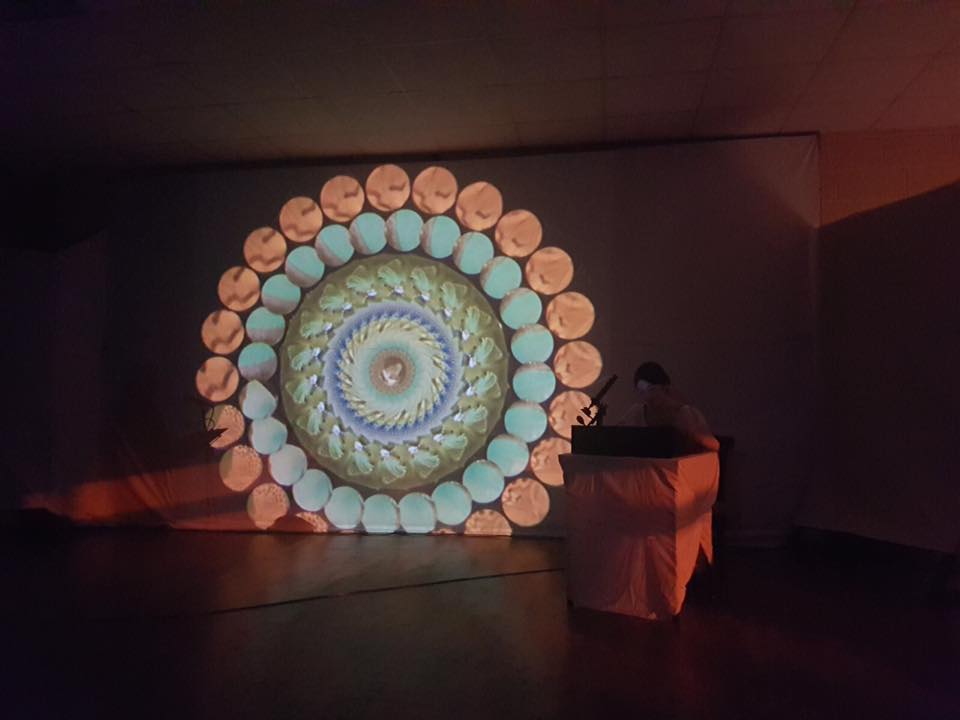

We were thrilled in 2018 to have been part of an immersive show devised by photographer Tina Claffey and artist Caroline Conway called ‘Mary Ward’s World of Wonder‘. Book the show today for your school, college or community!

Info HERE

FORMATION OF FERBANE BOG

Ferbane Bog SAC is estimated to be over 10,000 years old, occurring in a basin, predominantly underlain by limestone, with clay-rich tills above the bedrock. It has a discreet, raised dome and is a unique site in terms of this LIFE project, due to its proximity to the town of Ferbane. It is also just a short distance from another of our project sites: Moyclare SAC.

The raised bog here began to develop in the basin lake in which anaerobic conditions occurred. Complete decomposition of plant material was prevented. In time this un-decomposed plant material formed a thick layer of peat that rose towards the surface of the lake. Eventually the surface peat was invaded by sedges to form a fen. The fen peat layer thickened so that the roots of plants growing on the surface were no longer in contact with the calcium-rich groundwater. The only source of minerals for plants was now rainwater, which is very poor in minerals. Raised bog species, such as Sphagnum mosses begin to invade and eventually the fen becomes a raised bog.

The surface of a raised bog consists of a soft living carpet of vegetation, which floats on a material which is nearly all water. By weight, a raised bog may be up to 98% water and only 2% solid matter. This volume of water is held within dead Sphagnum moss fragments.

Raised bogs consist of two hydrological layers: the upper, very thin layer, known as the acrotelm;, is usually less than 50cm deep, and consists of living stems of Sphagnum mosses, recently dead plant material and water. The acrotelm has high permeability to water near to the surface, but becomes more impermeable with depth as the peat becomes more consolidated and decomposed (humified). Water movement and fluctuations mean that conditions in the acrotelm remain largely aerobic and it is here that microbial activity is strongest. The acrotelm is critical to the normal development and functioning of a raised bog.

Below this is a very much thicker bulk of peat, known as the catotelm, where individual plant stems have collapsed under the weight of mosses above them to produce an amorphous, dark mass of Sphagnum; fragments. Catotelm peat is typically well consolidated and often strongly humified. It is permanently saturated with water. Water movement through this amorphous peat is very slow, typically less than a meter a day. This is where most of the rain water is stored.

Deep drainage associated with turf cutting means Ferbane has suffered in the past, with the south and east traversed by drains.

In the past, peat cutting to the north and east of the site was significant. There is a series of lines drawn on the 1910, 6” map, which correspond with old turbary rights. More recent peat extraction is evidenced by abandoned sausage machine cut peat, at the north and south of the site (Kelly et al., 1995). The bog was selected for development as a peat source by Bord na Mona in 1983. This has not occurred and the site was subsequently transferred to National Parks and Wildlife Service ownership in 1996. The majority of the bog is in public ownership.

The 1910, 6” map shows planted forestry to the east of the site. This was probably predominantly Scots Pine. This has most likely been felled and regenerated over the years, with the invasion ofother species such as Birch.

FERBANE POWER & A JOB WITH ‘THE BORD’

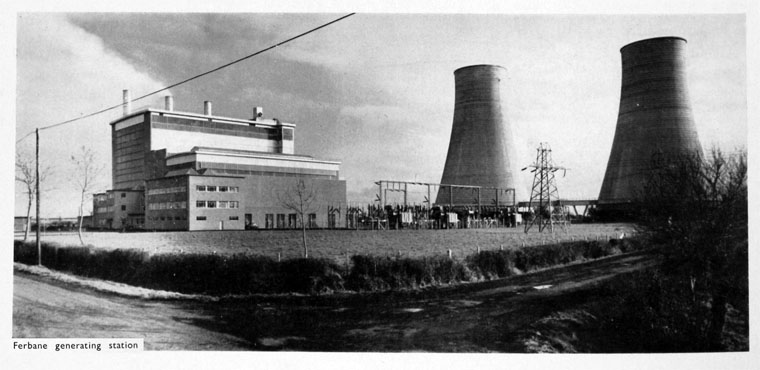

Bogs in this part of the country – and in particular the once common raised bogs – are synonymous with the fuel industry. Ferbane owes an awful lot to the now demolished power station, which employed thousands in the five decades it was operational. It was the first ever milled peat fired power station to be built and commissioned in Ireland, the first in the world outside the former U.S.S.R.

Construction started in 1953 and it was commissioned by the Electrical Supply Board (E.S.B.) in 1957 with the first development of 60,000 kilowatts. The second stage of development of a further 30,000 kilowatts commenced in June 1961, and was commissioned in January 1964. This brought the total capacity of the Station to 90,000 kilowatts, capable of producing about 400 million units of electricity a year.

At its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, the station burned 2,000 tonnes of peat daily, producing about 2 million units of electricity daily when its four units were at full load. The milled peat was brought in by train on narrow gauge lines, mainly from the Lough Boora complexes. Each unit consisted of a boiler, a turbine, a generator and a transformer. Boilers 1, 2 and 3 (first development) each produced 100 tons steam per hour, at a pressure of 30 kg/cm2 and temperature 440°C to drive Brown Boveri 20 MW turbines and directly coupled generators at 3,000 revs per minute. The 4th unit (2nd development) had a 130 ton/hr boiler giving steam at a pressure of 63 kg/cm2 and at a temperature of 510°C which drove a 30 MW Parsons Turbine and directly coupled Generator at 3,000 revs per minute. The electricity was generated at 10,000 volts and transformed to 110,000 volts for transmission into the national grid.

(Film from the Huntley Film Archives)

However, the station was getting old and by the mid 1990’s the obsolete station was contributing little to the National Grid. Closure was recommended for 1998. However, its closure was not without its controversy, as the Irish Independent reported in 1998 and the Irish Times reported in 2001. It had not provided power for almost three years before it was finally closed. Demolition took place in 2003, and the ESB have recorded its demolition HERE.

Had Ferbane Power Station survived into the 21st century, the destiny of Ferbane Bog SAC might have been different and may well have involved chimney stacks. However, the bog

There can be no denying that towns like Ferbane have suffered with the closure of the power plants, mechanisation and Bord na Móna’s long, slow exit from peat extraction. As journalist Rodney Farry outlines HERE in an Irish Times feature, a job with Bord na Móna was ‘it’: “For young men in Ferbane and the surrounding villages, landing a permanent position with “the bord”, as locals call it, brought job security and a guaranteed pension, rare in 1950s Ireland.”

FERBANE TRAIN STATION

Once-upon-a-time, Ferbane was a key stop on the former 17 mile branch from Clara to Banagher, constructed by the Clara and Banagher Railway and opened in 1884 (after a protracted construction as a large section went through bog). Clara-Banagher started out as an independent line but ran out of money a few times and was eventually taken over by the Great Southern and Western Railway, linking Ferbane to all the major lines and destinations.

The line lost its passenger service becoming freight only in 1947. The line remained in use for goods and occasional special services until it was closed in a tranche of branch closures all over the country in 1963.

A child plays on the platform as a CIE goods train bound for Banagher departs from Ferbane Train Station in 1960. (Pic: Roger Joanes/Ciaran Cooney/Eiretrains)

And a little over three years later: Ferbane Railway Station in 1964, with the line in the process of being dismantled. (Pic: National Library of Ireland.)

The former station in Ferbane remains visible to this day, with the station building, a Victorian structure built in 1884, surviving, along with the goods shed. The station is now reused, housing offices for the local Council. Architecturally, the design is both simple and functional, adorned by few enrichments like bargeboards to the gables, cast-iron rainwater goods and stepped brick cornice to eaves. Like a lot of midlands stations (and others on the Banagher branch), it was a combination of a single and two-storey building.

The former Ferbane Station today, with the goods shed (now a Council storage shed) to the rear. No train line remains.

Office space: the former Ferbane Train Station

However, the platform and road overbridge (which carried the N62) is long since demolished, and most of the line itself is long gone.

The branch left the Portarlington-Athlone line at Clara and Banagher Junction, just outside the town. There was also a station at Belmont.

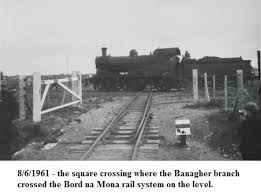

An unusual feature of the line was at Lemanaghan Bog, east of Ferbane town, where there was a unique flat level crossing with the narrow gauge Bord na Móna system serving the power station. All that’s left of this today is the remains of a gate post. For more, see the Eire Trains site HERE

COOLE CASTLE

Sir John MaCoghlan built Coole Castle on the banks of the River Brosna in 1575. It was the last of the MacCoghlan castles to be built. He erected it as a present to his second wife Sabina O’Dallachain. Formerly there was a mural slab in the castle with a Latin inscription translated in English as ““This tower was built by the energy of Sir John MacCoghlan, K.T. chief of this Sept at the proper cost of Sabina O’Dallachain on the condition that she should have it for her lifetime and afterwards each of her sons according to their seniority”

The whereabouts of the mural is unknown at present. In his will in 1590 Sir John left Coole Castle to his widow. Over the fireplace, in its original location, in the topmost room of the castle is a plaque written in Middle Irish which reads:

“SEAGHA (n) MAC (c) OCHL (ain) DO TINDSCAIN O SEO SUAS 1575” (“Sean Mac Cochlan began (this building) from this (date) 1575”)

Coole Castle, Ferbane.

Coole Castle, Ferbane.