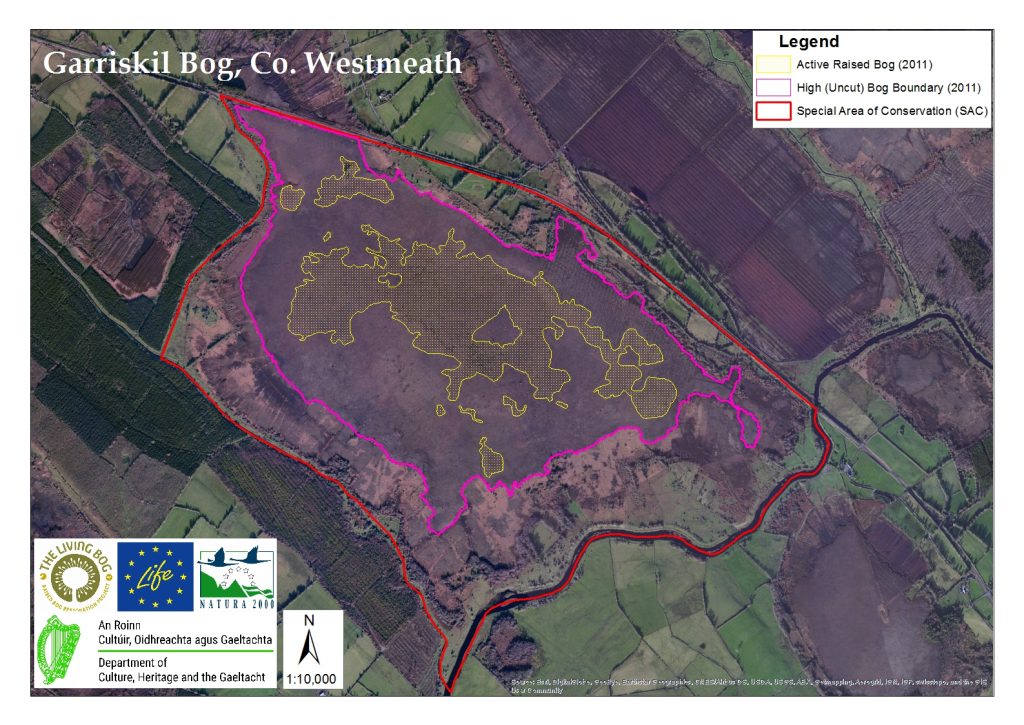

Garriskil Bog is a large raised bog with 51.7% of the original bog still present. It contains a large, wet high quality central core of active raised bog which comprises approximately 51 ha (30%) of the uncut high bog area. There are extensive, well developed systems of pools and hummocks present. It is a good wet bog with plenty of life.

Past drainage of the bog, associated with arterial drainage of the Inny and Riffey rivers and peat cutting, has unfavourably impacted on the site and led to widespread subsidence and drying out. The northern area of the site was also affected in the 1990s by intensive surface drainage which directly affected the area of ARB reducing it from 71 ha to 45 ha. Those drains were blocked by NPWS in the late 1990s and by 2014 the area of ARB had increased by 5.5 ha to 50.9 ha. There has been no turf cutting since the 1990s and though burning has caused damage in the past, there has been no severe fire in recent years.

FLORA OF GARRISKIL

Bog Asphodel

The bog mosses Sphagnum imbricatum, S. fuscum and the moss Leucobryum glaucum are important components of the hummocks, which are frequently crowned by the moss Racomitrium lanuginosum and sometimes colonised by Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus). The numerous areas of inter-connecting pools are mostly dominated by Rhynchosporion vegetation which forms floating rafts on the water surface. Typical plant species present include the bog mosses Sphagnum cuspidatum (generally dominant) and S. auriculatum, the liverwort Cladopodiella fluitans, White Beak-sedge, Bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), bladderworts (Utricularia spp.), Common Cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium) and Great Sundew (Drosera anglica). Brown Beak-sedge, a sedge species considered to be rare on a national basis, is present in some of the bog pools. The areas between the pools support occasional wet and quaking lawns of White Beak-sedge, as well as Bog Asphodel.

The vegetation of the rest of the high bog, including the DRB, tends to be dominated by Heather (Calluna vulgaris), Deergrass, Bog Asphodel, cottongrasses (Eriophorum vaginatum and E. angustifolium) and Cross-leaved Heath (Erica tetralix). The distribution and relative abundance of these species varies with peat wetness. Sphagnum cover is generally less than 30%. In these drier areas the cover of the lichen Cladonia portentosa can be locally high. Outside the ARB area, pool complexes are rare and where they do occur they tend to be dominated by shallow open water or algal mats. Small areas of Rhynchosporion vegetation also occur here, however the habitat is, in general, not well developed outside the ARB area. In a number of places the high bog is being invaded by Downy Birch (Betula pubescens) and pines. Often the pines are associated with small flushes dominated by species such as Purple Moor-grass (Molinia caerulea), Soft Rush (Juncus effusus), Bramble (Rubus fruticosus agg.) and Heather.

The large areas of old cutover bog provides an additional habitat where Purple Moor-grass and Heather dominate, along with cottongrasses, while in some parts Downy Birch woodland is developing. Along the north-east margin of the high bog a narrow band of fen-grassland occurs.

A relatively scarce lichen, Cladonia rangiferina, is found in abundance on and around hummocks in the ARB on the site (Douglas & Grogan 1986).

On a negative note, invasive species Pinus sylvestris and Rhododendron ponticum are found in several locations on the high bog.

FAUNA OF GARRISKIL

Great white fronted geese on the wing

The LIFE team are currently surveying the site and their fauna observations will appear here soon.

The following is based on information contained in NPWS in 2004: A flock of Greenland white-fronted geese (Anser albifrons flavirostris) (listed in Annex I of the Birds Directive) ranges over the midland lakes, including those close to the site (e.g. Lough Derravaragh). In the winter of 1993/94 this internationally important flock consisted of 346 birds (Fox et al. 1994). Garriskil Bog formerly provided an important feeding and/or refuge area for the geese, but Fox et al. (1994) report that the birds now feed mostly on intensively managed grassland and take refuge on the lakes. With rewetting it is hoped to entice the birds back to the bog.

A pair of breeding Merlin (Falco columbarius) (Annex I, Birds Directive) have been reported to hunt within the site and breed in a nearby conifer plantation. These are of high conservation importance.

Other birds using the site include hunting barn owl (Tyto alba) and small numbers of breeding redshank (Tringa totanus), curlew (Numenius arquata), lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) and snipe (Gallinago gallinago), with meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis) also occurring during the summer months.

We estimate that from project actions including drain blocking with peat and a small number of plastic dams, there will be an increase of Active Raised Bog on Garriskil by over 20%.

We restored the bog in 2018, taking 5 months to install almost 1,100 peat dams on the cutover and high bog. It is a beautiful sight from the air as these images show:

Blocked drains on the high bog at Garriskill Bog in Co Westmeath. Pic: Skyfab/Declan Murray for NPWS

The current conservation objective for Garriskil Bog is to restore the area of Active Raised Bog to the area present when the Habitats Directive came into force in 1994. In the case of Active Raised Bog, the objective also includes the restoration of Degraded Raised Bog. The Area objective for Active Raised Bog is 86.13ha.

Garriskil Bog in the Autumn of 2017. Pic: William Crowley

As its overall objective, this LIFE Nature Project aims at restoring the favourable conservation status of Active Raised Bog (Natura 2000 code: 7110 *Active Raised Bogs) through the protection and restoration of a selection of bogs within the SAC network.

Garriskil Bog SAC has is one of the 53 raised bog SACs designated in Ireland under the EU Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC). As such, this site is deemed to be of paramount importance as an example of Irish raised bog to be conserved and restored. It fulfils this role regionally as an excellent example of a Midland raised bog; nationally as one of the most valuable raised bogs in the country; and at the EU level as an adopted site of Community Importance. Additionally, potential for increase in the area of Active Raised Bog has already been observed at this site.

Garriskil Bog is of considerable conservation value. It is especially important because a large proportion of the uncut high bog comprises very wet active raised bog, which is unusual for raised bogs in the eastern half of the Ireland; because of its relatively good condition, the site is considered to be one of the best remaining examples of a raised bog ecosystem in the eastern half of the country.

Additionally, this site is amongst those most appropriate to reach the project’s objectives because the restoration works previously undertaken have shown encouraging results.

A Restoration Project was undertaken in 1998, which included the blocking of high bog drains: particularly to the northeast of high bog. Evidence of improvement including infilling was noted by Fernandez et al. (2005). This trend has continued, as confirmed by a 2011 survey. Active Raised Bog has expanded within this drain complex. Therefore, the blocking of drains at the site should be recorded as a very positive action with an increase in the area of ARB of approx. 5.75ha in the 2004/5 to 2011 period. Several new peat forming areas have developed at the sites as a result of rewetting processes associated with the blocking of drains.

In addition, some of the sub-central and central ecotope sections have expanded. This already demonstrated potential for increase in the area of Active Raised Bog will be built on during the LIFE project.

The objective in relation to Structure and Functions (S&Fs) is that at least half of the Active Raised Bog area should be made up of the central ecotope and active flush (i.e. the wetter vegetation communities). These values have been set as Favourable Reference Values. Degraded Raised Bog still capable of regeneration should be, according to the interpretation manual, capable of regeneration to ‘active raised bog’ in 30 years if appropriate measures are put in place (i.e. no major impacting activities are present and any necessary restoration works are implemented).

In the past the habitat area was considered to be all high bog not considered to be active, but this is now not accepted as much of the high bog can no longer be restored to active (see DAHG 2014). The remaining non-active high bog is considered supporting habitat for the Annex I habitats on the high bog. This supporting habitat is an essential part of the hydrological unit necessary to support Active and Degraded Raised Bog habitats.

The restoration of suitable cutover areas is essential for Active Raised Bog to achieve the favourable conservation condition at the site. Nevertheless it is acknowledged that a long period of time (i.e. over 30 years) may be needed after appropriate restoration works are undertaken on the cutover areas for the habitat to develop.

We have seen an increase of ARB on Garriskil in the 2004 to 2011 period by as much as 5.75ha so we are confident of seeing a large increase over 30 years.

See project results section of the website for how we did here.

Most of Ireland’s raised bogs are in the Irish midlands, but when it comes to actual centrality, Garriskil Bog SAC is perhaps the nearest to the exact centre of the island. And not only that, it has a unique history that takes in Bruce Springsteen’s ancestors, Ireland’s most unique bog train station, St Patrick, space exploration and discovery, Michael Collins and more besides… Truly one of Ireland’s best raised bogs, Garriskil’s intriguing social history and connections make it one of the most interesting.

The raised bog is located in the heart of the Irish midlands in County Westmeath, just 1km from the village of Streete, 3km from the village of Rathowen, 15km from the county town of Mullingar and 2km from the historic home of the fabled ‘Children of Lir’, Lough Derravaragh. Garriskill is also visible from the exact centre of Ireland: The Hill of Uisneach.

Garriskill Bog (which takes its name from the Gaelic ‘Garascal’, meaning rough nook) is a significant site in more ways than one. It is a remnant of a network of large river floodplain bogs which developed where the River Inny enters and leaves Lough Derravarragh (the Inny winds around the southern end of the bog below). Most of these bogs are now affected by human interference, some seriously wounded, strip-mined for horticultural peat, but Garriskill is an exceptional reminder of a once common landscape of this part of the country.

We will publish our survey results here on this site in late 2021, but our project chose this site with its 2011 survey in mind. Then, the large raised bog had 51.7% of the original bog still present and contained a large, wet high quality central core of Active Raised Bog (ARB) which comprises approximately 51 ha (30%) of the uncut high bog area. This living bog is actively peat forming with a high percentage of bog mosses, hummocks, pools, wet flats, Sphagnum lawns, flushes and soaks.

At 324.81 hectares it is one of the largest LIFE project sites is considered an exceptional example of a midland raised bog. It includes 170 ha of uncut raised bog and 154 ha of mostly cut-over bog (resulting from previous turf-cutting). The LIFE project aims to add over 30 ha of ARB to the bog – an increase of well over 20%.

So, how did we do? Well, it was one of the first sites we restored. In February 2018 and again between September 2018 – December 2018 we carried out extensive works on both the cutover and high bog installing almost 1,100 peat dams. The work was massive, but early indications are that the bog has made a remarkable recovery with previously bone dry areas of cutover now brimming with rare flora and fauna.

- Garriskil Bog SAC near Mullingar, Streete, Rathowen and Ballinalack. Pic: Skyfab/Declan Murray for NPWS

- Garriskil Bog Co Westmeath. Pic: Skyfab/Declan Murray for NPWS

- It’s like an alien landscape isn’t it? Garriskill Bog SAC by SkyFab/Declan Murray for NPWS

- Blocked drains on the high bog at Garriskill Bog in Co Westmeath. Pic: Skyfab/Declan Murray for NPWS

- Blocked drains on both cutover and high bog. Pic: Skyfab/Declan Murray for NPWS

Garriskil Bog is bounded to the south-east and south-west by the rivers Inny and Riffey and by the Dublin-Sligo railway line to the north with the former Inny Junction station close to the site. In days long before the car became the preferred mode of transport and when emigration was rife, the Inny junction (which overlooks the bog) was a place where many midlanders took their last look at an Irish bog. Uniquely it was, at one stage, the only train station in the entire British Isles not be serviced by a road! (See HISTORY section for more)

Garriskil Bog SAC from the air, with the Sligo-Dublin rail line running alongside (bottom right). You can see where the old Cavan-Mullingar line branched off to the right. A horticultural peat production bog is located to the right of the rail line. Pic: NPWS

This page belongs to the communities surrounding Derrinea Bog. Whether you are a local heritage group, a men’s shed, or a sporting organisation, this section of the Derrinea site is for you.

Stories and history from the area is currently being compiled by our Public Awareness Manager, Ronan Casey. If you have any interesting stories, photos, information or anything concerning Raheenmore Bog, please email ronan.casey@npws.gov.ie or call him on 076 1002627.

If you have a community web presence, or newsletter or information sheet you’d like to see reach a wider audience, don’t hesitate to let Ronan know and it will go up on this site.

We will also link to interesting people and events in the areas surrounding this important raised bog. We want to celebrate the past, present and future of this area.

The culture and traditions associated with bogs in Roscommon deserve to reach a wider audience and our Public Awareness Manager is keen for this aspect of our bogs to be celebrated just as much as the conservation and restoration of raised bogs.

At present there are no visitor facilities or recreational amenities on or near Derrinea Bog.

The bog itself is very dangerous to walk on and unsupervised visits are not encouraged or allowed.

Public access to the bog can only be arranged through the LIFE office, contact 076 1002627 or email life@raisedbogs.ie

Open days, school tours as well as public walks and talks are planned on Derrinea in the future.

Please check out our events calendar on the main page and also our social media

There is some information signage about the bog at that location. It is accessible from the N83 and R293 roads. Please note this cul-de-sac is used by local residents. There are no parking facilities.

Derrinea raised bog SAC is located just 5km north-northwest of another of our raised bog project sites, Carrowbehy/Caher Bog SAC which is much more visitor friendly.

Derrinea Bog SAC has a unique location in terms of our 12 project sites. Its lakeside location makes it a very interesting area.

Cloonagh Lough is a freshwater lake in the catchment of the Boyle River. The area of the lake is estimated to be 0.71 square kms with a large catchment area of some 47.93 square kms.

It is not extensively recorded if Cloonagh Lake beside the bog has significance, but a pair of crannóg sites on the lake would seem to indicate an ancient use and importance. According to a 1953 report from the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland, the river Anaderryboy enters the lake at the south western angle and carries down water through the large Keelbanda bog areas and the Feigh turloughs from Cloonagh Lough, Urlaur Lough and Errit Lough.

It eventually flows into the River Lung which, in turn, feeds the principal supply of water to the larger Lough Gara, a site of huge amenity and tourism value to the county.

Interestingly, Derrinea raised bog is located just 5km north-northwest of another of our raised bog project sites, Carrowbehy/Caher Bog which is much more visitor friendly.

At one stage this was huge raised bog territory. It is estimated there are approx. 70 bogs to be found in Roscommon, with the majority remnant raised bogs, but some blanket bogs occur on high ground in north Roscommon at Kilronan and Corry Mountain.

However, the history books did not necessarily rate this once very wet part of Roscommon with any great love. The Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland in 1900 wrote of the area: “In the western corner of the county are Loughs Errit, Cloonagh and Cloonacolly, beside each other; east of which is Lough Glinn (which gives name to the Village beside it), with finely wooded shores, an oasis in the midst of a bare, bleak district.”

The boggy district here was much referenced. The same publication notes this part of the county being of “the greater part flat, with much bog and marshy meadow land.”

A lot of this bog has been since been exploited.

The county takes name from St Coman. In the beginning of the 8th century, St. Coman founded a monastery where the town now stands; and the place was called from him Ros-Comain, Coman’s Wood.

Local links:

http://www.visitroscommon.com/ – Plenty of information on what to see and do in Roscommon county.

http://www.roscommon.ie/ – Portal for county local enterprise, local authority and tourism.

https://www.facebook.com/roscommon.ie/ – Active Facebook page celebrating the county.

http://www.discoverireland.ie/places-to-go-location/roscommon/22 – Discover Ireland’s take on Roscommon.

The current conservation objective for Derrinea Bog is to restore the area of Active Raised Bog to the area present when the Habitats Directive came into force in 1994. In the case of Active Raised Bog, the objective also includes the restoration of Degraded Raised Bog.

The Area objective for Active Raised Bog is 24.97ha. Detailed restoration plans will be available in time. At present, close to 2,500m of drains will be blocked on Derrinea using hundreds of peat dams and, in some cases where machine access will not be possible, plastic dams.

A typical peat dam two years after its creation

The objective in relation to Structure and Functions (S&Fs) is that at least half of the Active Raised Bog area should be made up of the central ecotope and active flush (i.e. the wetter vegetation communities). These values have been set as Favourable Reference Values. Degraded Raised Bog still capable of regeneration should be, according to the interpretation manual, capable of regeneration to ‘active raised bog’ in 30 years if appropriate measures are put in place (i.e. no major impacting activities are present and any necessary restoration works are implemented). In the past the habitat area was considered to be all high bog not considered to be active, but this is now not accepted as much of the high bog can no longer be restored to active (see DAHG 2014). The remaining non-active high bog is considered supporting habitat for the Annex I habitats on the high bog. This supporting habitat is an essential part of the hydrological unit necessary to support Active and Degraded Raised Bog habitats. The restoration of suitable cutover areas is essential for Active Raised Bog to achieve the favourable conservation condition at the site.

It is acknowledged that a long period of time (i.e. over 30 years) may be needed after appropriate restoration works are undertaken on the cutover areas for the habitat to develop. Restoration works along the western cutover of another of our project sites – Killyconny Bog SAC – indicated the occurrence of pioneer ‘active raised bog’ vegetation 8 years after these were undertaken.

Based on the close ecological relationship between Active Raised Bog, Degraded Raised Bog and Rhynchosporion depressions, it is considered that should favourable conservation condition for ‘Active Raised Bog’ be achieved on the site, then, as a consequence, favourable conservation condition for the other two habitats would also be achieved.

No restoration works have taken place at this site to date. The LIFE prokect will be the first to undertake work on site. Drainage will be the main focus as drainage associated with the areas of former peat exploitation is the most threatening of current activities at the site – although peat-cutting no longer takes place.

The control of trees and shrubs whose regeneration is natural is not a major problem at this SAC.

The central active portion of the high bog at Derrinea features an extensive area of pools, quaking flats and well-developed hummocks. Areas of Rhynchosporion vegetation are largely confined to this central active area. The pools are generally dominated by the bog moss S. cuspidatum, which is usually accompanied by S. auriculatum, White Beak-sedge, Bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), Common Cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium) and Bog-sedge (Carex limosa).

The site supports two large pools (15 to 25 m in diameter) and these are infilling with rafts of Rhynchosporion vegetation. Surrounding the pools, quaking flats have good bog moss cover, with the moss Campylopus atrovirens and Great Sundew (Drosera anglica) also present. The hummock-forming bog moss S. imbricatum is found around the pools. The scarce Sphagnum recurvum var. tenue has been recorded from the site. Other species which occur on the hummocks include Heather (Calluna vulgaris) and Cross-leaved Heath (Erica tetralix).

The vegetation of the degraded bog areas tends to be species-poor and dominated by robust plant species such as Carnation Sedge, Heather, Deergrass and Bog Asphodel. The Sphagnum cover is usually less than 30% and pools are rare. Locally, in areas where there are pronounced surface slopes, there are erosion channels dominated by White Beak-sedge.

A small area of heath, developed over a till mound, occurs at the southern end of the bog and this adds to the ecological interest of the site. It has an almost complete cover of Heather, with occasional Sessile Oak (Quercus petraea).

Whilst much of the high bog surface at this site is partially degraded due to drainage and turf cutting, the active bog is still remarkably wet and of good quality. But peat cutting will cause further degradation to the raised bog habitats.

Flora of Derrinea Bog

Derrinea Bog has extensive wet areas composed of central and sub-central ecotope and active flush. Pools are abundant in the central ecotope and are of the type characteristic of western raised bog, frequently having a low Sphagnum cover.

Racomitrium lanuginosum – A woolly fringe moss found on Derrinea

Other western indicator species such as the woolly Racomitrium lanuginosum, Campylopus atrovirens, and Pleurozia purpurea are also frequent on this bog. The overall Sphagnum cover in the central ecotope is approximately 40% with Sphagnum cuspidatum in the pools (along with occasional algae) and hummocks of S. capillifolium, S. austinii and S. fuscum all present.

The inter-pool area is dominated by flats of Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum) and has a relatively low Sphagnum cover. Towards the south and the west of the centre of the bog, sub-central ecotope dominates with pools being less frequent and the overall Sphagnum cover down to 10-20% (Fernandez et al. 2005).

The cover of Carex panicea, another western indicator species is higher in this sub-central ecotope and there is also a small patch with a high cover of Rhynchospora alba and Bog Cotton, common cottongrass or common cottonsedge, (Eriophorum angustifolium) and Hare’s Tail Cottongrass (E. vaginatum). There are also three infilling pools on Derrinea that are considered to be active flushes. These pools support the highest cover of Sphagnum on the bog.

The largest pool on Derrinea Bog covers an area of 0.7ha. This pool is almost completely covered with Sphagnum cuspidatum and S. denticulatum with S. papillosum and S. magellanicum found along the pool margins. Hummocks of S. capillifolium, S. austinii, S. subnitens, and S. fuscum are all present here along with flush indicators such as Molinia caerulea and Aulacomnium palustre.

A second pool has a lush cover of Sphagnum including S. fallax in addition to those species present in the larger pool. Carex limosa covers large tracts of this pool where there is open water. A large variety of species has been recorded from this pool area including Juncus bulbosus, J. effusus, Pleurozium schreberi, Hylocomium splendens, Rhytidiadelphus loreus, Carex echinata, Aulacomnium palustre, Empetrum nigrum, Vaccinium oxycoccos, and V. myrtillus. The smallest of the pools is circular-shaped and covered with Sphagnum cuspidatum and Eriophorum angustifolium. The water table in this pool was recorded as being 0.5-0.7m below the surface in 2004 (Fernandez et al. 2005).

Narthecium ossifragum, or Bog Asphodel – Illustration in: Jakob Sturm: “Deutschlands Flora in Abbildungen”,

Within this small raised bog, approximately two-thirds of the uncut high bog dome comprises non-active raised bog communities, which are subject to drainage effects from drains on the high bog and the surrounding cutover. The vegetation of these areas tends to be species-poor and dominated by more robust plant species, particularly by Carnation Sedge (Carex panicea), Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum), Calluna vulgaris and Trichophorum germanicum. Locally, in areas where there are pronounced surface slopes, there are erosion channels dominated by Rhynchospora alba. The Sphagnum cover is usually less than 20% and pool areas are rare and where they do occur they tend to be tear pools largely devoid of plant cover.

Areas of the Rhynchosporion vegetation are largely confined to the central ARB portion of this small site where there are numerous pool areas though there is also Rhynchosporion dominated vegetation in erosion channels in areas towards the margin of the bog. The largest area of this type of vegetation occurs to the west of the centre of the site in an area of sub-central ecotope where white beak-sedge (Rhynchospora alba) co-dominates the vegetation with Eriophorum angustifolium and E. vaginatum. White Beak-sedge (Rhynchospora alba) also occurs along the edges of the pools throughout the central and sub-central ecotopes being more frequent in the shallower, drier pools. It is also present in the three infilling pools and is usually accompanied by Sphagnum cuspidatum, Menyanthes trifoliata, and Eriophorum angustifolium in these pools.

Fauna of Derrinea Bog

Derrinea Bog supports a wide range of faunal species. However, the LIFE team are currently surveying the site as there is a lack of documented site-specific data relating to the fauna of this bog.

Red Grouse have been observed here in the past. Other fauna to have been recorded here includes: Irish hare, otter, fox, skylark, meadow pipit, hen harrier, merlin, kestrel, snipe, curlew, lapwing, common lizard, and common frog.

A large number of invertebrates would call Derrinea home, including the rare marsh fritillary butterfly (pictured above), bog-pool spider, water striders, dragonflies, ants, moths, beetles, great green bog grasshopper, water beetles, and many flies.

We will publish the results of our surveys here in late 2017.

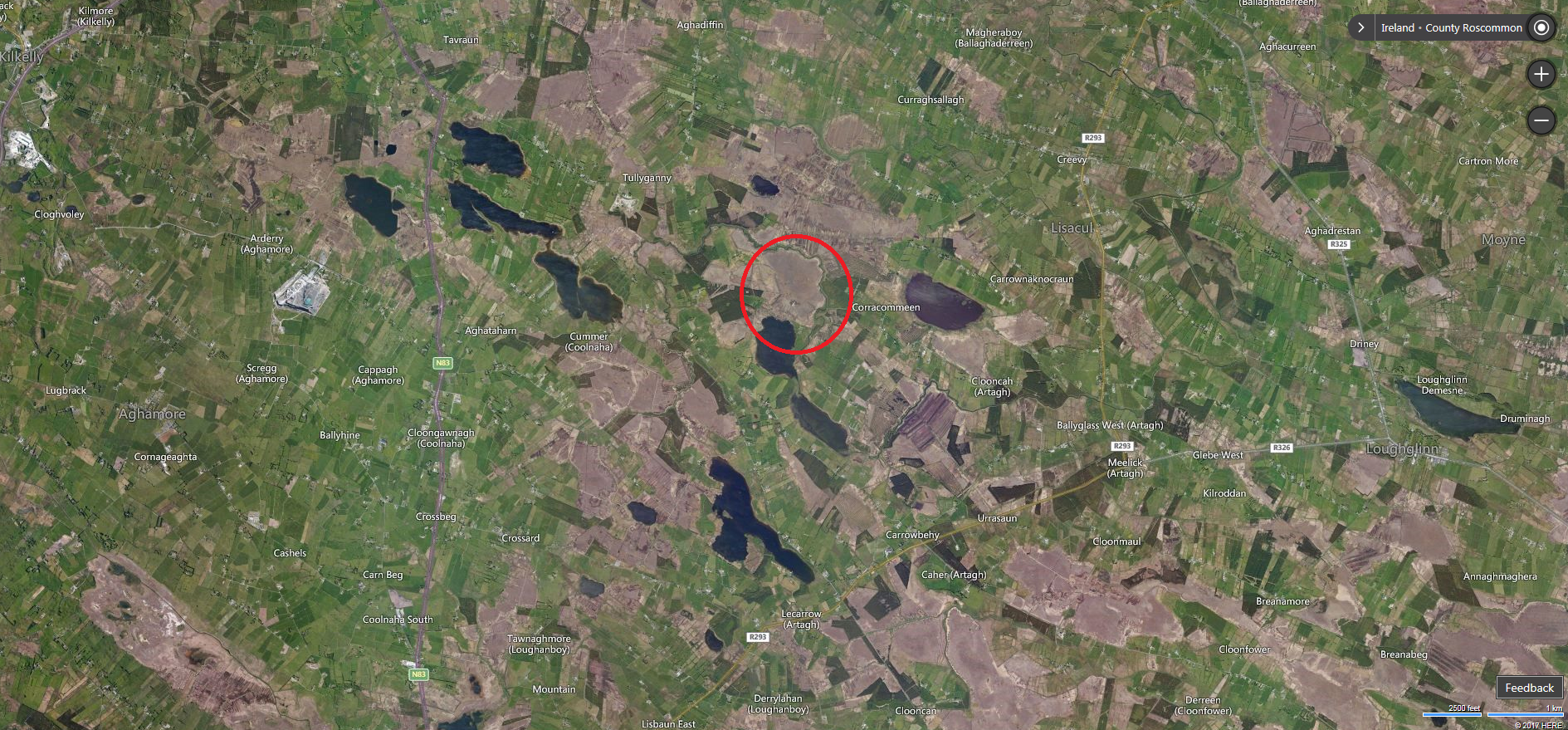

With a lakeside location in a bog-rich part of rural northern Roscommon, Derrinea Bog is one of the most picturesque LIFE project sites, and with a total surface area of 86.18 hectares, it is also one of the smallest.

Derrinea Bog is located approximately 10km northwest of Ballyhaunis, just east of the Mayo / Roscommon border. It lies close to the northern side of the freshwater lake Cloonagh Lough and is bordered to the north and east by the long and winding River Anaderryboy, which emanates from Cloonagh Lough and links it to Errit Lough before eventually feeding into the much larger Lough Gara.

Derrinea Bog is a small Western Raised Bog (Cross, 1990), which consists of a single peat body, geomorphologically classified as a Ridge River C type bog (Kelly et al., 1995). It is full of interesting features. For example, a small till mound is found towards the south of the site and there is a drumlin feature in the north-west.

The bog has a roughly rectangular and relatively simple shape, and has been cut away most intensively along the southern edge. Despite this, Derrinea Bog is in good condition, with favourable restoration prospects.

There is a good cover of Active Raised Bog (ARB) with over 17 hectares (or 31.09%) of the high bog area alive and well, consisting of central and sub-central ecotope and active flush.

We are currently surveying the site, but according to the most recent survey conducted in 2012 high quality raised bog, in the form of central ecotope and active flush, covers 45.28% of the total ARB, and in the case of central ecotope has an overall Sphagnum cover of 33-50%, with pools covering 26-33% of the total area. Pool cover varies throughout the different areas of central ecotope, but is as high as 40-50% in the north-west of the site. Sphagnum lawns, hummocks and hollows are also part of the micro-topography of the central ecotope.

Active flush consists partly of a large pool (or soak) with a high cover of Sphagnum (mostly S. cuspidatum), and numerous island hummocks that support other Sphagnum species, and species characteristic of active flush.

Sphagnum Cuspidatum, with leaves blown onto the bog.

Degraded Raised Bog (DRB) covers 37.79 ha (68.91%) of the high bog area. It is drier than Active Raised Bog and supports a lower density of Sphagnum mosses – Sphagnum cover reaches 26-33% in the wettest of the community complexes recorded – and it has a less developed micro-topography with permanent pools and Sphagnum lawns generally absent.

Degraded Raised Bog at the site consists of sub-marginal, marginal and facebank ecotope and inactive flush. Depressions on peat substrates of the Rhynchosporion are found in both Active and Degraded Raised Bog, but tend to be best developed and most stable in the wettest areas of Active Raised Bog.

The LIFE project here aims to increase the amount of ARB by as much as 10 hectares through restoration methods on the high bog and cutover.

Derrinea Bog is a site of high conservation importance as it contains examples of the Annex I habitats active raised bog, degraded raised bog and depressions on peat substrates (Rhynchosporion). The site is a good example of a western raised bog (one of three bogs of this type in our LIFE project) and although it is rather small, the quality of the habitats is generally good.

A number of other raised bogs and calcareous lakes lie in close proximity to this site and together they constitute one of the most important ecological areas in the east Mayo/Roscommon region.

Bog country – Derrinea SAC is the circled site

This page belongs to the communities surrounding Moyclare Bog. Whether you are a local community group, heritage group, men’s shed, drama group, play group, school, or a sporting organisation, this section of the Living Bog site is for you.

This is an area of Ireland where even the smallest local story or photograph could make a big impact. What may be ordinary to you, is extraordinary to others. What you might not think is interesting could be of huge value to someone else. Stories, such as those on our Carrowbehy and Killyconny pages, about the turf-cutting days, local folklore and local stories are needed to build up a truly national picture of our bogs.

If you have a community web presence, or newsletter or information sheet you’d like to see reach a wider audience, don’t hesitate to let us know and it will go up on this site. Contact us via Email: peatlandsmanagement@npws.gov.ie

We will also link to interesting people and events in the areas surrounding this raised bog. We also wish to highlight the traditions associated with turf in this area. Whilst this project is about restoring a number of raised bogs, we want to celebrate everything to do with bogs, past present and future, so if you have stories and memories of days on the bog, please let us know and we’ll share them.