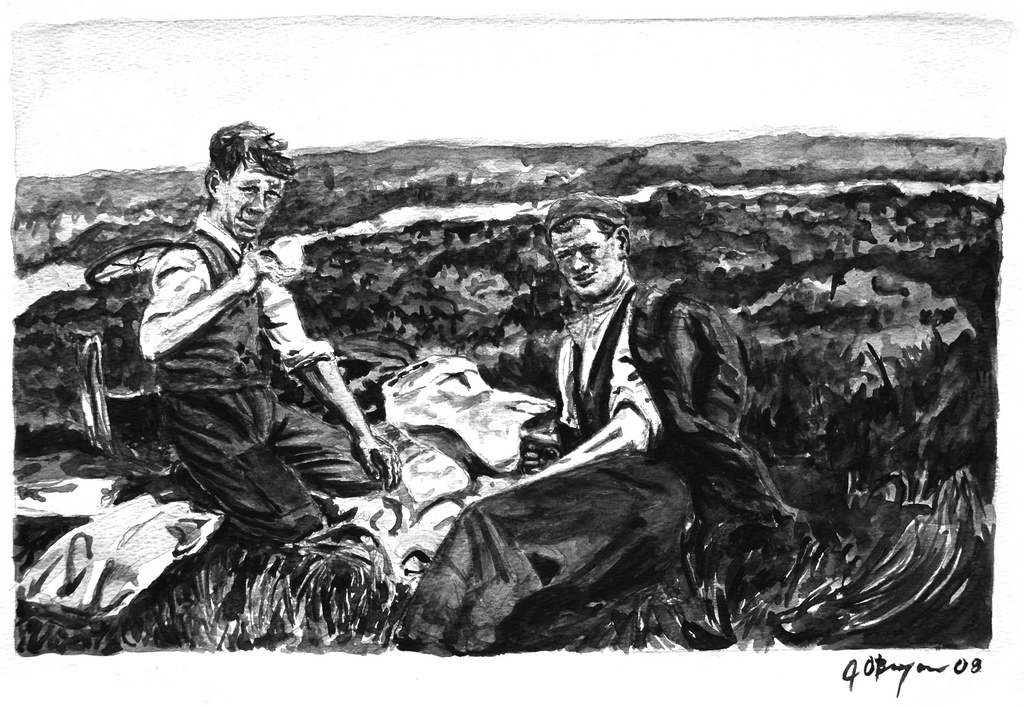

John K Lynch grew up in Mullagh and has a vivid recollection of working on the bog over 50 years ago. He shares them with us here*

“The story of Killyconny Bog, Cloughbally Bog, Killycunny Bog, Leitrim Bog, The Big Bog, or whatever name you may know it by, is set to become a wonderful public amenity over the next few years… so let’s help it succeed along the way.

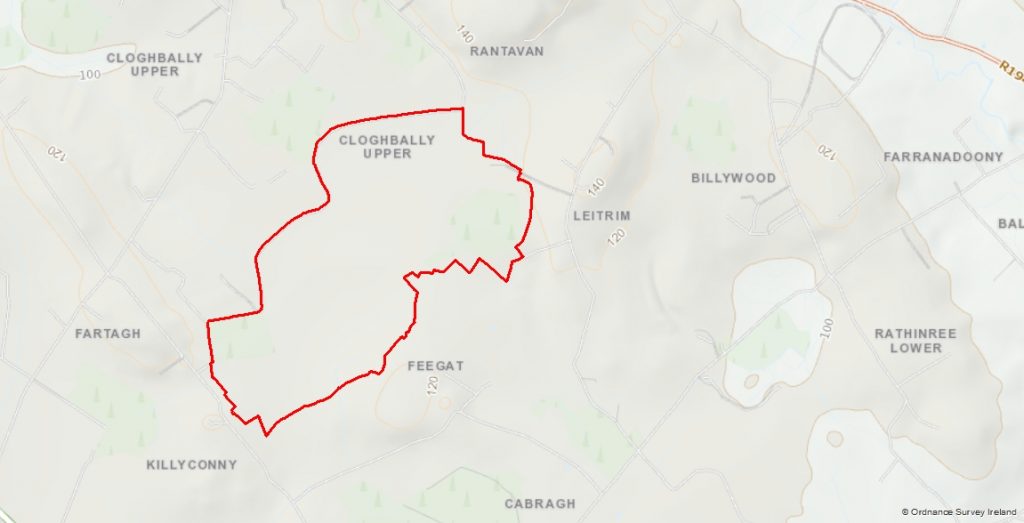

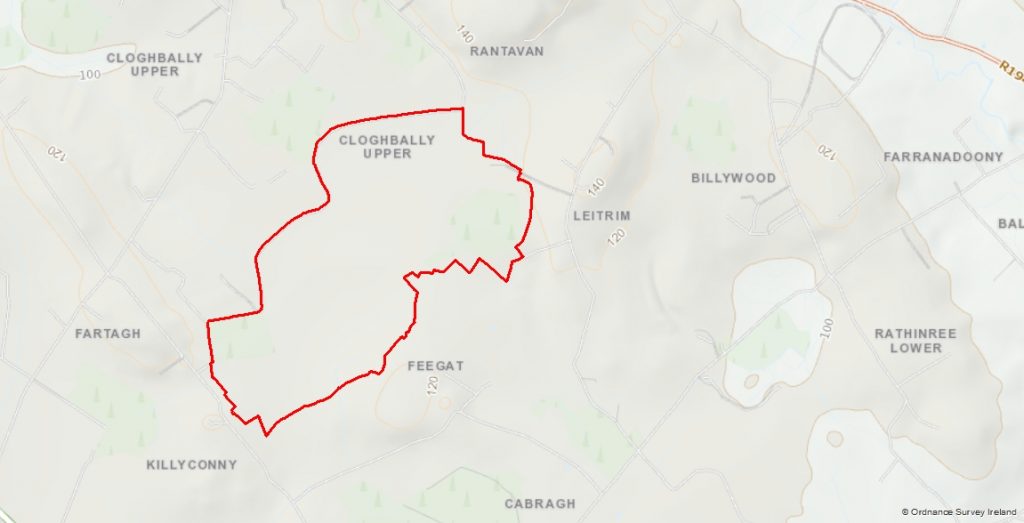

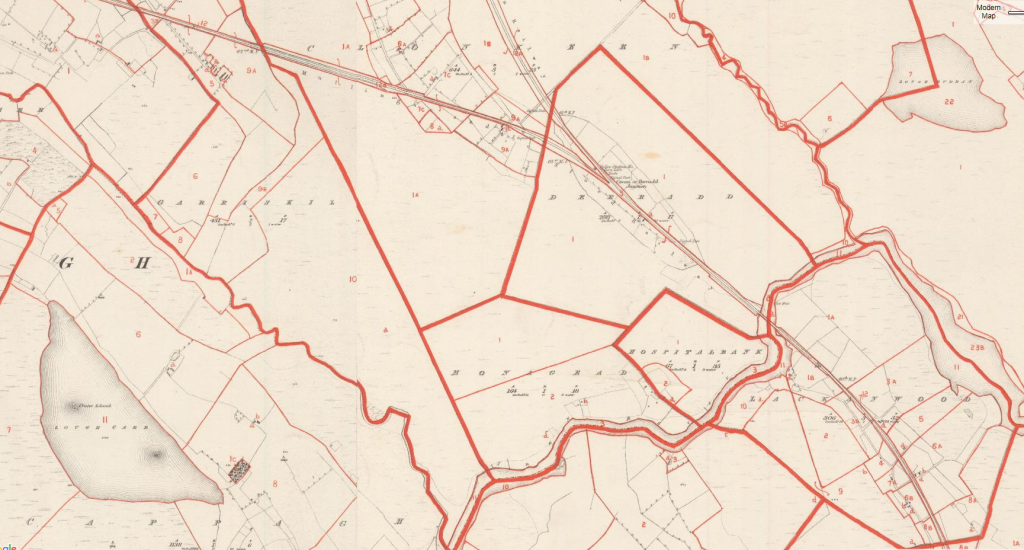

The present bog area in question covers approximately 190 hectares (472 acres). However, it is interesting to mention the Down Survey carried out in Ireland by William Petty from 1656 to 1658. This was the first ever national survey of land in the world, whereby the resident Catholic Irish landowners had their land confiscated and redistributed to Commonwealth soldiers and other Adventurers . The Survey maps of the period show a continuous stretch of bog – 1,709acres, 1 rood and 24 perches (691 ha) extending South East from Murmod to the Leitrim/Fegat and Killyconny townlands on the Co. Meath border, and name it “The Great Bogg” and “The Red Bog” respectively.

At that time the area would have been for the most part inaccessible, flooded with a non existent road structure and basically unrecognisable to us today. Prior to the Cromwellian Survey, the area would have been natively referred to in the spoken language of the time, Gaelic. The adjacent townland of Feegat in the South East area of the bog has its roots in the Gaelic form of the name “Fiodh na gCat” translated “The Wood of the Cats” – these animals would were wildcats, similar in appearance, but much larger and vicious than the present domesticated cat and were very common in the countryside. Dr. Philip O’Connell a noted historian of the early 1900s and native to the area stated that the Great Bog was also known as “Monuorogata Bog” – “Moinfhear na gCat” – that is the marshy meadow or bogland of the cats. The 190 ha of Killyconny Bog as it is now officially referred to, is for the most part as it was topographically over 350 years ago.

Memories of the bog are fast disappearing and it is not untrue to say that most people connect the word to a wet morass of swamp and marsh – a wild foreboding place to be, especially in bad weather – where one could easily vanish, never to be found again after being swallowed up in its black mass! Bogs of course are much more interesting places than that. They are in effect, a reservoir and library of the earth’s flora over thousands of years and of course are recognised as the earth’s important carbon sink. After the retreat of the ice sheet covering Ireland some 15,000 years ago, the stage was set for the formation of our bogs. Irish bogs are between 5,000 and 10,000 years old.

They are unique in the world and a very important feature of Irish landscape. Rich in biodiversity, they require to be waterlogged to achieve growth and this poses problems to adjacent agricultural land that can be overcome. Our ancestors committed gruesome acts on fellow human beings, buried their remains in bogs and the natural preservatives contained in turf bogs – tannin – leave perfectly preserved bodies when found hundreds of years later – albeit the skin being tanned like leather. Subsequent examination by forensic archaeologists leads us to a better understanding of the deceased’s diet, lifestyle, age, etc. We describe the product of the bog as turf, the same word as used in the German language while the English use the word peat. Bogs insofar as our neighbours on the adjacent island were concerned, were in their mind-set only associated with the native Irish and therefore used in a pejorative sense, to describe the Irish as “boggies”. I suppose it was as a result of the preponderance of bogs covering our landscape, which over the centuries were the only source of fuel to heat our primitive dwellings and modern homes, even up to the present time. Carbon dioxide emissions and the phasing out of fossil fuels are some of the reasons that have now ensured that our remaining bogs are places of preserved natural heritage and sites of minor industrial archaeology with accompanied associated folklore traditions.

My earliest recollections of “being on the bog” was at 5 years of age in 1955.

We had a “bank” or plot of turf on what we called Leitrim Bog and it came with the farm of land. Turf banks were measured in perches (and these are not the fish!) – 1 perch equaled 5.5 yards which is equivalent to approx. 5 metres. My father (Harry) and my grandfather (John) cut some turf that summer.

John and Mat Reilly, Leitrim had an adjacent “bank” and as far as I can remember, they also cut turf that season. John Bracken, John Gibney, Nicholas Dolan, Ballintlieve, George Bough, Rantavan, Patsy Cassidy, Shancarnan, Jimmy Smith, Leitrim were regulars working on the Rantavan side of the same bog. I also seem to also remember Peter Lynch, Leitrim on the bog and cutting somewhere near us. John Travers whom we often spoke with and two or three other turf cutters worked on the Killacunny side, but I don’t remember their names.

Leitrim Bog was relatively quiet compared to the Rantavan and Cloughbally side where all the action was and which was a hive of activity. I distinctly remember that the boundary of our turf bank was marked by a crab apple tree which my grandfather had planted years earlier and which was growing there until relatively recent times. It was a great marker and aid to location as all turf banks looked the same. In addition, there was mature beech trees planted on both the Lynch and Reilly banks. The two families it would seem must have planted them in the very distant past – over 100 years ago – although this may not be entirely true for other reasons. This bank of turf was quite near to Rantavan townland, but to access it required travelling the long distance by public road up to Leitrim taking the lane off to the right leading down to the bog, crossing a “kesh” over a main drain and into the afterbanks of the bog – a distance of over 1 mile. Years later in the early 1960s, I helped my father cut some of the beech trees with a crosscut saw. The Reillys’ also cut some of their tress the same year. This was hard work, but the big crosscut saw seemed to fly through the huge timbers.

We relocated to cutting turf on the Rantavan side from 1956 onwards. This turf bank was adjacent to our farm and very convenient. As we did not own the bank, my father rented around half a perch of bank (approx 2.5 metres) and paid the sum of £1 and 10 shillings annually to the bog agent who resided in Virginia. This man would frequently carry out an inspection on all working banks to ensure that everyone was up to date in their payments. We usually rented a half perch (2.5 metres) but there were many such as the Daltons who cut a full one perch in width bank of turf.

Cutting the turf

The annual trip to the bog was over a period of two to three weeks, with a workforce of a “slane’s man” and “catcher” or “barrowman” and occurred when the crops were planted and there was time to spare – it was built in to the farming calendar.

The preparation of the turf bank was all important. As this was a raised bog, it had to be stripped of its top layer, generally to a depth of at least two feet – this layer was composed of heather, roots and what we called the light brown turf. It would have been of very poor burning quality. Huge chunks of this were tumbled on to the low bank and into the existing boghole that remained from the previous year. This was firmed up to allow a man and wheelbarrow work with safety and ease when cutting commenced. The top bank was cleaned and squared off until it was as level as a billiard table.

Turf cutters were very exact and took great pride in the preparation of their bank. The implement used in turf cutting was called a side slane – it was generally manufactured to the shape of spade, but was much more refined, smaller and lighter. It had a shortish handle with a tee on the end. But locally, many slane’s men had handles made to their requirements. Its’ sides and forward edges were razor sharp and it was a dangerous working tool. I don’t remember any cutter using a wing slane – this was a similar type slane of more robust proportions with an additional metal wing which was turned up on one side during its manufacture. There was talk locally that some cutters had tried it out.

On the low bank the “catchers” job was to have his wheelbarrow prepared, stand in a suitable position and be able to anticipate and catch the thrown sod from the slanesman, place it on his barrow then catch the next sod and repeat the process over and over again. The barrow man was also skilled at his work – it was his job to make life easy for the cutter by being in the correct position to receive the sod otherwise tempers would rise between the two. Many slanesmen would feed turf to two barrows in order to expedite the work. Each sod had to be placed on the barrow in a particular way, built up until a full load was on board, thus enabling the contents being emptied neatly and tidily – without breaking the sods – in neat rows, perhaps up to 50 yards away.

When work was finished each day, the slane was hid in a particular spot and the barrow was likewise put out of sight, not that anyone would even think of taking the implements!

And so it went, cutting down and down into the bog, with the turf getting darker and darker the deeper you went, until finally one came to uncovering bog timbers and sticks, which signified the end of the turf.

On other occasions, mud turf was discovered at depth and this entailed a different operation to recover the mud which was very valuable and as good as coal.

Going deep brought its own challenges – water trying to seep in to the cutter’s workplace – he was always very vigilant and sometimes it was a continuous battle to keep water out and avoid being flooded. This was where proper preparation of the bank in the first place paid off. People were very careful in their work and in the absence of modern day health and safety, all were very conscious of the dangers in their working environment. I never saw or heard of an accident on the bog despite the very sharp slane and the deep, unprotected bog holes and drains. There were many children helping out on the bog alone, especially when the turf was being “footed”. But we always obeyed the instructions of adults which were drilled into us and therefore we all came home safely. There was no wandering off to explore and maybe get into difficulty or trespass on another bank.

If the weather was good and dry, turf spread out on the after banks dried and hardened and were put into what we termed “squares” – that is four sods laid out with gaps between each and placed one on top of the other to a height of about five or six high. This method hastened the drying and hardening process and after a week or two, the dry turf in these quares were gathered up and put into small clamps which somewhat resembled a rectangular triangle. These were left to dry out further and either eventually made into very large clamps or reeks on the bog or drawn home by horse and cart, put into sheds, or reeks in the haggard. Some families might make two years turf initially, thus ensuring that they only burned turf that was two years old as this would provide better heat and burning quality. The Dalton family from Mullagh were noted for their quality of turf and much of it was three years old.

Eating on the bog

Meals on the bog were eagerly looked forward to – the hard work and the pristine bog air worked up a good appetite. The grub was simple and nourishing – kitchen facilities were basic and military like. A fire was set at an open safe and sheltered location around noon – in a hollow depression – and usually in the same place as in previous years.

We had a sort of shelter which we used for eating – this was on an adjacent disused bank and was beautifully constructed – a sort of an open low cave-like structure, facing out of the prevailing wind. The previous makers hollowed out the shelter from the growing bog and so it remained for years. Food was simple home-made brown bread and butter, chicken sandwiches and eggs which were boiled in the bog water. I recall that spring water for the tea was obtained from a well on John Bracken’s land. A further cup of tea and bread was availed of in the afternoon.

At the end of each day, great care was taken to extinguish the fire completely, by pouring water on it. I never recollected even a small fire occurring during turf cutting season.

Turf cutting families

John Gibney, Mullagh and John Bracken, Leitrim and George Bough, Rantavan were cutting a short distance away from us on Leitrim Bog, as previously mentioned. On the Cloughbally side, Hughie Reilly, Rantavan and his sons Owen and Michael were annual turf-cutters and interesting people to have a conversation with. I remember their father Hughie as a mild-mannered, soft-spoken man.

The Reilly family spent three weeks cutting turf as they had a large bank. They had an ass who was called “Neddy” and a cart equipped with flyers, which they used to draw their turf home. Their sister Bernadette came to the bog from her home twice daily, accompanied by her collie dog “Bruno” – at 1pm and at 4pm – with tea and sandwiches for the men. They never lit a fire on the bog for fear of it getting out of control.

Andy, P.J. and Seamus Mc Kenna from Lislin were cutting on the bank near the Reillys and they also had a large bank to harvest. I remember also the Tully’s from Lislin – their Christian names escape me – they were further over and working away quietly.

Johnny Smith from Cloughbally, also cutting nearby and was always in good form with a joke and a laugh. Stephen Carolan, Rantavan another very reserved man was also on a bank in that general vicinity, as was Kevin Reilly from Lislin – his house was the former home of my great, great grandfather, James Lynch.

Saved turf required to be transported from the soft banks for loading on to large carts on firmer ground. Slipes were often used for this purpose and pulled by an ass. The ass was the ideal animal for working on the bog as its strength and weight facilitated taking loads over very soft ground. In other parts of Ireland, more commonly in Kerry, animals called “Bog Ponies” were used for these tasks.

Vincie Lynch, Rantavan and his brother Mickey were further on and they too had an ass and cart. The Dalton family of Willie and Bernie from Mullagh were excellent turf cutters with particular attention to detail and took great pride in their output and huge reeks of turf. Most days, they brought their horse and cart to the bog to take home some of last year’s turf. Mrs Dalton paid a visit to her sons on the bog at least three times during the season. They always had their fire down and the kettle boiling in anticipation of her visit.

Pat and Tommy Bradley from Rantavan also cut turf. Val Rotchford, Oliver Gilsenan, John Brennan, Matt Feddis, Matt Dalton, Denis and Bobby Nulty, Jack Reilly from Rantavan and his son Tony, all were annual turfcutters further down the line. The Heerys from Lisnagun and the O’Reillys (my uncles) from Ryefield, Munterconnaught and the Muldoons, cut over the Fegat direction.

There were many, many more from near and far whose memory escapes me. The month or so on the bog was a time of social interaction between neighbours from far and near; it was also a welcome break from the manual and tedious work of the farm… it was a great break to get to the bog “for a holiday”.

My father remembers that in his youth, the bog was a hive of activity with hundreds up and down the line busy making provision for the winter months and indeed for all year round, as fires in houses were the only source of cooking – there was no electricity or bottled gas those times.

The bog line was untarred at the time so it wasn’t an easy bicycle ride from Mullagh. Daltons’ was a very well-known and welcoming ceile house in Mullagh where every visitor was assured of a warm roaring fire.

Wildlife on the bog

My recollection is that there was a proliferation of wildlife on Killycunny Bog and the adjacent area. General drainage of farmland was poor and water levels were high. The bog acted as a sponge and released water on a continuous basis, even in dry summers.

The water was unpolluted and pure – older residents would testify that bog trout were in abundance in the larger and deeper streams. I remember seeing on only a couple of occasions, a bog trout in the deep part of the stream adjoining Farrelly’s land at Cloughbally.

Local people remember it being common to catch these trout for their meals and certainly eels were in abundance and a tasty meal.

Farming was still being carried out by horses; oats was grown and either cut by the mowing bar or binder and stooked in the fields. Most people grew an acre or more of other crops such as potatoes, turnips or kale. All of the foregoing factors ensured that wildlife in the vicinity of the bog had therefore a plentiful supply of food and shelter.

The Curlew was a very prolific bird on the bog and in the adjoining bottoms. It was very reassuring to hear their lonely-sounding call which you knew signified that all was well in the adjacent moorland.

The call of the Wilduck was very common and these were equally at home in the myriad of drains around the bog.

Pheasants were not that common as gun clubs were not established – however, wild pheasants could be seen feeding around stooks and stacks of corn in the fields.

Red Grouse were also on the bog but they were few in numbers – my father remembered when their numbers were relatively plentiful nesting in the deep heather and eating a diet of young shoots that grew on the afterbanks.

Red Partridge was also common, as was Snipe whose call, “drumming”, you would hear in the spring time.

Smaller birds such as the Pied Wagtail were common and nested in crevices in the turf banks.

Moorhens or Waterhens were very common and at home in the ideal nesting and foraging conditions provided by drains and relatively still water. Crows, though not associated with bogs, had their rookery in tall scots pine trees on Paddy Farrelly’s land, on the other side of the bog line.

The Cuckoo was also a very common bird and could be heard with great regularity from early spring as it flew among the trees on the edges of the bog. And where you hear the Cuckoo there are Reed Warblers who make their nests – in which the Cuckoo lays her egg – among the reeds.

Sadly with modern drainage, these reeds no longer grow and so the habitat of the reed warbler is lost and, consequently, the Cuckoo. Nature is indeed a very delicate balance.

Woodcock were also prevalent but difficult enough to observe. There was the odd Kingfisher at home on the faster flowing bog drains that came off farmland. These invariably had what we called minnows or “pinkeens” for their daily diet and these small fish seemed to be in abundance in particular areas of the streams. Holes in the soft peat banks provided readymade nesting sites for kingfishers. Dragonflies of all sizes were another visible, very common and colourful insect as they hovered over bogholes and turf banks. There were some quite large ones and were always a mystery to us, as to how they survived. Somehow, for whatever reason, they don’t seem to be as numerous nowadays, and certainly not as big as they once were.

Midges for such a small insect were an infernal annoyance and would literally eat you alive in the late evenings. Bernadette O’ Reilly always wondered at the number of bats she noticed flying at dusk, as she went home on the loaded ass and cart with her father via the bog line – the preponderance of midges was the answer. She was also blessed by the sight of many Barn Owls, flying silently around dusk and earlier, again while on the bog road. Perhaps the owls were hunting the bats for food which were hunting the midges!

The holes in numerous mature trees in the area and a short flight away in Mortimers, facilitated their nesting and also at that time, several old corrugated and disused stone sheds were ideal habitats.

Frogs were numerous and the readymade still pools of water proved to be excellent breeding habitats. Mammals such as Hares were quite common, and were visible running across the fields on the edge of the bog. It is therefore true to say that the bog and its general environment at the time was protection and home to quite a variety of wildlife.

Glow on the bog

My father remembered seeing at certain times of the year an unusual phenomenon of a glow or faint light coming off the wet bottoms at night time; these adjoined the bog and he could never say what caused this luminescence at low temperature! Perhaps the habitat has changed and whatever was glowing has become extinct…

Essential tools of the trade

The Slane. (Slean as Gaeilge) These were manufactured for the most part locally and generally by a blacksmith. This item was a prized and valuable possession. The blacksmith made almost everything that was needed in the farming line. He was an important man and his status and pecking order in society was somewhere between the Parish Priest, the Schoolteacher and the Miller. With his anvil, bellows and a stout sledge, all accompanied by muscle power and driven by an inventive brain, it was indeed possible for him to make literally anything. He also made spades and shovels, first cousins of the slane!

Blacksmiths such as P. Clarke who had a forge at the time in the townland of Killeter on the Mullagh to Bailieborough road made slanes amongst many other things. Other slane makers in the general locality would have been Mr Mc Entee (aka “The Toy”) who operated a forge at Cross, Mullagh and Tommy Flanagan’s forge at Ryefield, Mounterconnaught, Virginia – this was a very advanced forge and also made ploughs, etc. Terry Boylan was a busy blacksmith at Virginia Road Station and his son Mick carried on the business after him (a high class restaurant now operates from this former forge). All of these and other numerous blacksmiths were capable of turning out a slane if required.

The bog barrow was generally constructed by the local carpenter and was of easier construction than the normal working barrow with sides. Makers of these were carpenters such as John King, Bailieboro who also made carts, gates, slipes and feeding troughs and sold them at Mullagh Fair; the Gaynor brothers of John, Owen and Paddy of Cornaglea, Mullagh made barrows, slipes and horse carts; James Farrelly, Cornakill, Mullagh also made barrows and slipes. Kelletts in Virginia also sold barrows.

The slipe was a common farm vehicle designed for conveying small loads from awkward places and pulled by a horse, pony or ass. It was of stout timber construction on two raised wooden runners that were shod with a light steel plate to facilitate its smooth travel over ground and protect the runners from wear. This was an excellent means of transporting turf off the bog to another suitable location. In short, it was a sort of Irish sleigh or sled and every farmer had one for performing numerous farm asks and was especially suitable for the youth. They were made to various sizes but generally were no more than four foot in width and perhaps six feet in length.

It is safe to say that all of the above essential items for bog work and turf cutting were manufactured in the general locality by artisan craftsmen and would have been used season after season.

Curative properties associated with the bog

It was commonly agreed – rightly or wrongly – that bog air was possessed of particular goodness; that time spent on the bog breathing this refreshing air could only make one feel much more relaxed. There may be quite a lot of merit in this long held belief as air flowing over a bog is cleansed and infused naturally with micro particles of the flora growing in the area and the odours emitted from the breakdown of peat.

Bogs are generally devoid of adjacent large urban housing estates, traffic and factories and therefore are naturally occurring pollution free environments. All good for one’s health!

Persons working on the bog were encouraged to go barefoot, except for the turf cutter who risked injury to his exposed feet with the slane. After only a few days on the bog, one would notice that their feet took on a yellowish brownish pigmented colour. This came about as a result of the tannin and other properties coming in contact with the skin and as far as I know, was quite harmless and may have been beneficial for some skin ailments. When making mud turf on the bog, it was customary to tramp the mud (break it down to an even consistency) in your bare feet. After a hard days barefoot work on the bog, your feet would feel very refreshed – no need for deodorants or powders.

My grandfather had an unusual method of helping to heal an open wound or cut to the skin which was handed down through the generations. It involved going to the bog and taking some of the mesh like fauna (more commonly known as Sphagnum Moss) growing on top of the boghole water and placing it over the cut, thus sealing it, covering it with a bandage and speeding up the healing process.

Modern science has since discovered and proved that this Moss is indeed sterile and ideal for dressing wounds. Much the same as propolis from a bee hive acting as a barrier against disease in the hive and a mild cure for a sore throat. These locally known, home-based first aid treatments came about as a result of long term observations by our ancestors and though primitive, probably saved many lives in the past.

Other uses of turf.

It was common for the roof of a primitive animal shelter or shed to be made of turf. The turf surface on the after banks in these instances was scraped clean of heather, lifted and roughly rolled up in sections about eighteen inches wide with a depth of about six inches. It was then placed tightly as the outer layer over a lattice roof of sally rods covered with rushes. The walls were of rough stone and the rear wall of the structure would probably have been a boundary ditch of a field thus keeping building to a minimum with ease of construction. This would have been a warm enough shelter for animals and in the not too distant past, we Irish had to live in such structures during and after the famine and in many instances, these dwellings were located on bogs and in deep gripes that were likewise covered with sods of rolled turf.

Building a Kesh (Gaelic: Ceis)

To gain access to the bog from the roadway or adjacent land required in many instances, the construction of a small bridge over large drains and this structure was commonly referred to as a “Kesh”.

This was basically a wicker type structure made of trees, small branches, rushes, sods, etc. and the word itself is Gaelic for a wicker basket. Interestingly, turf was sold in the past in “kiskes” or “keshes” – large wicker basket measures.

Keshes or small wicker type bridges were very common all over Ireland. The kesh was of sound though primitive build and well capable of taking the weight of a horse and cart fully loaded with turf. They could in theory be built to any specification. My father had to rebuild a “kesh” on several occasions and from the memory of helping him with the task, the process was as follows:

– After selecting the narrowest and most robust area on either side of the drain and sound bank on the bog side, several “sally” trees were cut and stout strong lengths were placed across the drain, imbedded into the banks. The width would have been sufficient to take a horse and cart with safety and it was important to place several lengths of this timber in the centre to support the weight of the horse and it’s pull on the load. Likewise, particular attention had to be paid to the area carrying the narrow cart wheels.

– Following on, smaller lengths of fresh cut timber were laid at right angles in rows on the main supports. This then was covered in rushes and a thick layer of bog sods was laid on top to complete the job.

– There were some variants to this construction but basically all cesi builds were similar. After a short time growth would appear on the structure and make it that bit stronger. In many instances, it was impossible and too dangerous to attempt such an enterprise and turf had to be taken to the roadside by a slipe. Indeed, some reeks of turf were built initially at the side of the road rather than on the bank to save valuable time and labour.

Conclusion

The Great Bog Of Mullagh or Killycunny Bog as it known to my family, was of great importance to the native Irish down the centuries. Populations prior to English rule were numerous millions more than today with most living in rural areas. The Brehon Laws were composed of a huge body of intricate legal tract over a long period of time and to support these laws, required a substantial population.

We will never know but we can surmise that Killycunny Bog or the Bog at Mullagh provided a ready-made source of heat, shelter for the homeless, some curative qualities and food over the millennia for this large population.

Bogs are still very dangerous places because of the abundance of deep watery bog holes from times past and camouflaged drains with overgrown heather waiting to take the unprepared. To make it possible for generations to enjoy with safety Killycunny Bog, it would therefore be very remiss of us in these enlightened times, not to take the necessary measures to protect and enhance that existing resource created over the millennia, and in memory of our native relations who came from near and far and took so little of it while experiencing dire poverty.

Note from the author: Background

I am conscious that there are many others more knowledgeable and far better experienced than me to comment on this subject and The Living Bog would therefore be delighted to hear from you.

For what they are, my thoughts and recollections above are not meant to be a definitive statement that all would have experienced, but rather my own account and as we all see and observe things in different shades of light, you the reader, are asked for your story, to add to this general body of knowledge before it is lost. Get in touch with Ronan from the LIFE Project or any committee member at St Killian’s Heritage Centre if you experience difficulty putting pen to paper and you will gladly be helped.

If it is to be revived locally, the annual “Bog Day” festival – being out in the “Bog Air” – should hopefully revive our memories and give us all a better experience and understanding of the hard work of our ancestors in the not too distant past”

Disclaimer:

*Please note, this is a personal account of life on the bog, and is published by kind permission of the owner and author of this work, John K Lynch. It is in no way intended to cause offence to living or dead and the LIFE team disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. If amendments or edits need to be made, please contact us and we will pass them on.

The information provided here is designed to provide a background on the bog. It is not meant to be used for any other purposes, and our publication of it does not constitute endorsement.

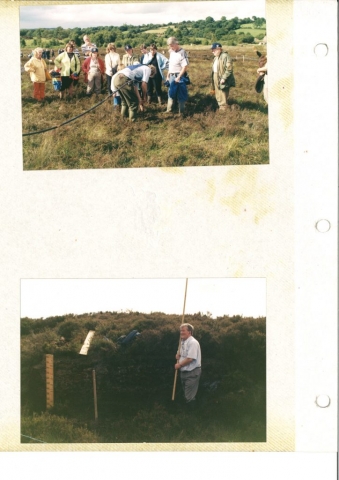

Cissy Tighe demonstrating Beesoms, or heather brushes during one of the original ‘Day on the Bog’ events on Killyconny Bog in the 1990’s.

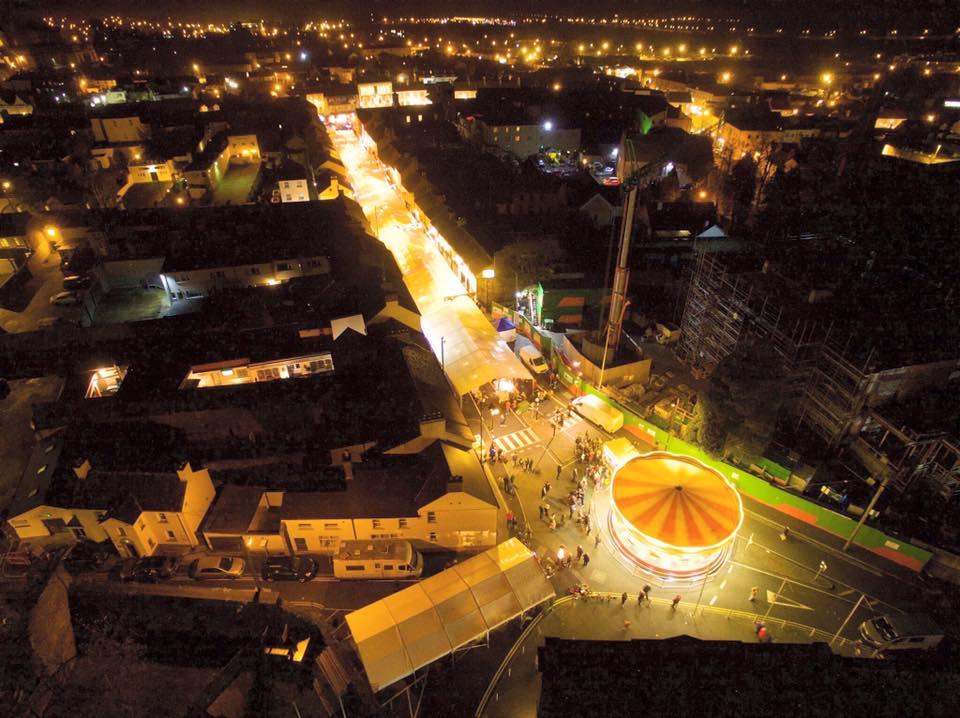

Killyconny Bog was once upon a (recent) time home to a truly Irish occasion: the Mullagh ‘Day on the Bog’.

You can read more about it HERE in this archived IRISH TIMES article (please note: A subscription may be needed to read the article in full)

With thanks to local man Jim Smith of Rantavan, Mullagh, who has had a great interest in preserving Killyconny raised bog for many years, we present rare and restored footage of three of the great ‘Mullagh Bog Day’ community events, from 1997, 1998 and 1999.

The days were organised by the St Kilian Heritage Trust. The aim was to recreate the part the bog played in rural life and at the same time to heighten awareness of the importance of conserving as many as possible of our bogs for future generations. Each featured a packed programme of events, including:

• Guided tours of the bog

• Flora and Fauna talks

• Pond-dipping and Wildlife

• Exhibition of turf-cutting and turf-cutting competition

• Exhibitions of tools used on the bog – from the slean to barrows to bog crafts to heather ‘beesoms’ (brushes)

• Mini-farm

• Traditional music and song

• Story-telling and comedy

• Irish dancing

• Refreshments, and much more…

We are very lucky that Jim filmed these events and the restored footage is here for generations to enjoy. If you see a familiar face and can help us identify everybody in the videos, please drop us a line, email ronan.casey@npws.gov.ie or phone 076 1002627 and we’ll endeavor to update the credits. The videos are property of Jim Smith. Feel free to share on social media to give the Diaspora of Cavan and Meath a great window to our recent past.

1997

1997 was the first year of the Bog Day and it was a historic one for Cavan, as they beat Derry to become Ulster Champions! The bog event was great craic, as Jim’s video below details, and later on in the video, some of the Cavan team come to Mullagh with the trophy, and wild celebrations ensue on both the bog and on the streets!

1998

1998 saw the event grow, and it was a huge success with a big crowd enjoying the very best Mullagh had to offer. There was plenty to see and do, and the importance of preserving the bog and restoring it became a reality and was much-talked about locally. 1998 was an historic year too as the bog was officially designated an Special Area of Conservation after Michael D Higgins had signed the Habitats Directive a year earlier.

1999

1999 was another great year for the Mullagh Bog Day, as Jim’s video shows the community really getting behind it. Sadly, despite the interest and the good weather the event was blessed with for its three days, it was to be the last staging of the event… for now…

2017

The event was resurrected by a committee featuring members of the LIFE team and St Kilian’s Heritage Council in 2017, when a smaller-scale staging took place on Saturday August 26, as part of National Heritage Week. This successful event will pave the way for bigger community events on the bog in the future.

A section of the large crowd which enjoyed a walk and talk on Killyconny Bog SAC during our ‘Mullagh Day on the Bog’ event for Heritage Week 2017

As reported on our BOG BLOG page, the event attracted a large crowd, with all aspects of the bog covered, from turf-cutting days to today’s restoration plans.

The day commenced with old turf-cutting equipment displays and talks at St Kilian’s Heritage Centre in Mullagh town, honouring the turf cutting past of the bog. A number of local elders spoke about the days on the bog before the large crowd was bussed out to Killyconny Bog SAC for a walk and talk by Ronan Casey and Jack McGauley. There was over 50 in attendance and more left waiting at the Centre such was demand! The crowds were not just local, with tourists from Asia, Great Britain and America, plus people from Derry, Dublin, Kells, Navan and Drogheda as well as local media (Anglo Celt) and Cavan County Council reps all enjoying an informative walk and talk along the edge of Killyconny Bog SAC. It is hoped the event will be built on for next year and there is considerable local community enthusiasm and involvement for it to grow.

Check out the photo gallery from the day here:

PICTURES OF OLD

With thanks to local man Brendan Clarke, here are some photographic memories of the original ‘Day on the Bog’ events, mainly 1998.

Locals in wonder as an ecologist talks them through the story of raised bogs during a Killyconny Day on the Bog in the 1990’s

GET IN TOUCH

This page belongs to the communities surrounding Killyconny Bog SAC and the town of Mullagh. Whether you are a local heritage group, a men’s shed, a sporting organisation, a tourism and development association, a charity group or even just an individual with something interesting to put out, this section of the Killyconny site is for you.

Stories and history from the area is currently being compiled by our Public Awareness Manager, Ronan Casey. If you have any interesting stories, photos, information or anything concerning the bog or the surrounding areas, please email ronan.casey@npws.gov.ie or call him on 076 1002627.

If you have a community web presence, or newsletter or information sheet you’d like to see reach a wider audience, don’t hesitate to let Ronan know and it will go up on this site.

We will also link to interesting people and events in the areas surrounding this important raised bog. We want to celebrate the past, present and future of this area.

The culture and traditions associated with bogs in Cavan, Meath and the North-East deserve to reach a wider audience and our Public Awareness Manager is keen for this aspect of our bogs to be celebrated just as much as the conservation and restoration of raised bogs.

Please note that by publishing any articles, or sharing details of events etc ‘The Living Bog’ (LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032), DAHRRGA, and EU LIFE are not endorsing them. Merely we are opening a forum to the local community. The views expressed will not necessarily be those of LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032 or any other body associated with it.

Mullagh Bog: An oasis for now and a resource for the future*

By Jim Smyth, Rantavan, Mullagh – Originally published in the ANGLO CELT newspaper in 1997.

Mullagh Bog started forming about 10,000 years ago after the last Ice Age. As the climate became warmer the one to one-and-a-half mile ice sheet began to melt leaving behind in the landscape debris of soil, pebbles and boulders. Large mounds of this debris formed into what today we call drumlins and between many of these badly drained hills, lakes formed in the hollows. As the ice retreated northwards it left the classic drumlin shape – sharp on one side and drawn out on the other in the direction of the retreating ice. Numbering thousands, the drumlins gave rise to the so-called ‘basket of eggs’ topography.

Large boulders called erratics can still be seen throughout the drumlins. Marks or scratches on these boulders sometimes give an indication of the direction of the ice. Often, these non-local boulders were used by man in the construction of his sacred monuments, in fortifications, or as markers for burials.

After the melting of the ice a large shallow lake was created, e.g. as at Mullagh/Killyconny/Cloughbally Bog as we know it today. The climate then being moist and cool favoured the development of vegetation, forming fen and as it became more solid – bog. The moistness ensured a plentiful supply of water for its continued growth and the cool temperature limited the rate of evaporation.

The ground floor of the lake would have formed a chalk-like marl because of the poor drainage andf would also help hold the water. The three ingredients that favour bog growth are: The extent of rainfall; The low temperature which reduced evaporation; And the soil which restricts the drainage. Under these waterlogged conditions dead plants along the edge of the lake do not fully decompose and they begin to form a peat and to act as an anchor for further plant growth and over hundreds of years this accumulates and reduces the size of the lake progressing from lake to fen to raised bog.

The dominant plant that grows on the surface is called ~Sphagnum Moss. The moss is very important in the formation of the bog because it acts as a huge sponge drawing up the water with it as it grows.

During the long history of its growth, the temperature remained almost steady. However, about 4,500 years ago the annual rainfall decreased. This caused the bog to dry out to some extent and allowed the invasion and establishment of a pine forest. This forest survived for some 500 years until the climate became wetter again. The bog recommenced growing and the surface became wetter and the trees and vegetation died. The moss took over and these plants became buried. From time to time pine tree trunks are uncovered by turf cutters.

The area of raised bog at Mullagh covered approximately 1000 acres. It is confined to the shallow basin of the former lake. It will not grow beyond this point as the amount of rainfall that it receives limits its further spread. If it were in the West of Ireland with its higher rainfall and moist climate, then the Sphagnum moss could continue to grow over the landscape and it might become a blanket bog.

Seeing that such a high percentage of Mullagh bog is still in its virgin state is unusual in Ireland and Europe. It appears that over the years, with traditional turf cutting, that the bog grew enough each year to compensate for the removal of fuel for local consumption. However, this situation has changed dramatically for the worst in recent years with the arrival of mechanised turf cutting equipment and the drainage of the bog.

The sponge is becoming drier with each passing year. In our locality the bog acts as a massive sponge. In times of flood the bog is a major outlet in soaking up the water and preventing massive flooding. In times of drought the bog gives up its water to the local area. Therefore, a well working bog acts as a buffer between the local community and drought and flood. If the bog is to be allowed to be drained indiscriminately then the level of water in Mullagh Lake may fall and this too has implications for everybody, the lake being the town’s water supply and the overflow being a valuable water source for cattle.

Recently, a preservation order was placed on a large section of the bog and we not need to begin to realise the valuable resource and friend this bog was and can be for the people of the community now and into the future.

With more road networks being planned, opening up the countryside to industry and housing estates to follow, it is all the more important to preserve out boglands to support our water levels to meet our future needs.

Bogs themselves are very interesting places. At first, raised bogs appear to be dull, flat and lifeless. But by taking a closer look one discovers a rich wonderland of flora and fauna. It is one of the last retreats of our indigenous wildlife and many of our rare plants and herbs. A lot of this wonderful diversity was destroyed the last time the bog was burned. Hopefully through increased understanding this disaster will never happen again. Since the burning a lot of the fauna is at infant stage, and a wide variety of plants are repopulating the high bank. There are many different species of Sphagnum Moss growing, adding to the variety of colour. The bog is a safe roosting area for wildlife to breed and the heather provides extra protection.

Bogs have great preserving powers due to the lack of oxygen. Many articles and ancient objects have been uncovered in bogs. They have also been used to store butter and meat to keep it fresh and cool. Human remains have also been found in a well preserved condition after hundreds and thousands of years.

Turf

The main use of the bog at Mullagh has been the production of turf for use in the home. To walk on the centre of the bog it is very wet and springy, which is its healthy state. Along the perimeter it has dried out considerably and is encroaching on the centre of the bog, though it has still the traditional humped back profile of the traditional raised bog. In fact the bog is almost all water, as high as 95%, but when it is cut into sods and exposed to the sun and wind it contracts and becomes hard and dry and makes the ideal domestic fuel.

When making turf the top layer of peat or scraw is removed as it is unsuitable for fuel, but was a great insulator of heat in thatched houses. Having removed the scraw a special spade with a wing on the surface is used to cut the turf. The sods are then laid out to dry on the bog surface. This special spade is called a ‘shlane’. When the turf has become sufficiently dry on the low bank it is then stacked in reeks. The saving of the turf in years gone by lasted well into the Autumn. With modern machinery the rearing period is much shorter.

No major threat existed to the bog, until today with the arrival of modern machinery. The bog is not ours to destroy. Its survival may be an essential part of the independence between man and landscape. Kill one and the others suffer. Before large scale drainage took place, the bog would have contained 90-95% water, but today it is much less and the bog is dying. In order to ensure its survival and continued growth these drains will have to be closed off. Neighbouring farmers will have to be consulted on this matter to encourage co-operation rather than confrontation.

The future

Ireland is the most westerly country in Europe. Most of the peatlands on mainland Europe are now extinct. To conserve our bog it must be seen in this broader European context. We are fortunate enough to have a substantial raised bog in our Parish that is suitable for conservation and exploitation. Many other European countries have cut away all of their bogs and are now artificially trying to recreate bog growth conditions at enormous expense. They now regret not having the foresight to conserve some of their living bogs. For this reason they are keen to get involved in helping Irish people to preserve their boglands. The Dutch Foundation was set up in 1983 to raise money and to protect endangered bogs.

Financial incentives are available to farmers to preserve their banks on the bog under the REPS programme. Bogs are reckoned to be ten times greater at purifying the atmosphere than the rainforests.

Because of the diversity of habitat both on the bog surface and the surrounding area, they could become very interesting from an educational and tourist point of view, especially for school projects. The raised bog could be used for teaching Biology, Ecology, Chemistry, History, Geography and Folklore. It could also be used by photographers and ornithologists and observers of wildlife through the building of hides for observation.

The Irish Peatland Preservation Council are engaged in a campaign lobbying the government, promoting public awareness and education. The campaign is focused towards conservation of raised bogs as the threat of extinction to this unique habitat is now a reality. However, conservation should not be seen as an activity of a select committee, but part of an overall plan bringing benefits to the whole community. It is in everybody’s interests to preserve the bog and try and improve on its present state. The time for conservation is now. We must realise the treasure we have in our landscape and its wildlife. It would be intolerable to allow the unchecked destruction of an Irish landscape feature without making an effort to ensure that it is conserved for our future generations.

Conclusion

We have seen from the above how important it is to ensure the healthy functioning of the bog as a water regulator and as an oasis for wildlife, plants and herbs. We have also seen that the bog and its different systems could also be used as an educational tool for various levels of students in the parish and from outside, maybe we could look into getting some Masters and Doctorates compiled on our bog. We have also seen that this could become a tourist attraction for Irish and Foreign watchers and photographers of birds, wildlife and flora. It can also be seen as a way of recreating the story of the bog and the people who lived there and the way they managed from day to day.

It would be a pity to pass through a lifetime without making a positive contribution to the well-being of our environment.

Many other communities like ourselves have been surrounded by what for Europeans and Academics was a unique place and the community never realised it. We now know that we have a resource of potential, to find out its true extant we need to get a Resource Audit of the bog, an estimation of its current health and then what it would take to conserve it and to sensitively exploit its educational, cultural and tourism potential. Then, as a community, we could decide how we would manage this friend in our midst.

Jim Smith, Rantavan, Mullagh, Co Cavan.

*DISCLAIMER: The above article is the full version of an article submitted by local Mullagh man Jim Smith to a number of bodies and journals in 1997. We are happy to republish it on ‘The Living Bog’ website. Please note that republishing is not an endorsement of the article. Views and points made in the above article are not those of the ‘The Living Bog’ LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032 or that of DAHRRGA or EU LIFE. This article appeared in an edited form in the Anglo Celt newspaper in 1997:

MULLAGH BOG – AND WHY WE SHOULD PRESERVE IT

The area of Mullagh that can be classified as a raised bog covers an area of approximately 1000 acres. If present levels of production are allowed to continue unchecked, within a few years we will have nothing worth preserving. Many bogs are now faced with the threat of extinction. Do we want the same thing to happen to our fine example of a raised bog? Once lost, they cannot be replaced. Now is the time to realise the threat and act responsibly. There are a number of reasons why it is so important to preserve our raised bog.

The dominant plant on the bog is Sphagnum Moss. There are different species of this moss on the bog, adding to the variety of colour. Because of drainage, a wide area along the perimeter of the high bank is much drier than further inland and therefore has not as good a population of plants further inland.

To have a raised bog in one’s area is a huge asset from various points of view. The bog probably dates back 10,000 years and because of the way it has grown in that time a lot of important information is preserved there. Samples of bog oak can be seen in old houses used over windows and doors. Our bog acts as a massive sponge in our locality. In times of flood the bog is a major outlet and in times of drought it is a huge reservoir. The bog can help control water levels in river catchments. If the bog is allowed to drain then the level of water in Mullagh Lake may fall and that has implications for everybody – the lake being the town’s water supply and the overflow being a valuable water source for cattle.

Because of the diversity of the habitat both on the bog surface and in the surrounding area, they could become very interesting from an educational point of view, especially for school projects. The raised bog could be used for teaching biology, ecology, chemistry, history, geography and folklore. Conserving our bog must be seen in the European context. Most of the peatlands on mainland Europe are almost extinct. We are fortunate to have a substantial raised bog in our Parish that is suitable for conservation. Many other EU countries have cut away all of their bogs and are now trying to artificially recreate bog conditions at enormous expense. They now regret not having had the foresight to conserve some of their living bogs. For this reason they are keen to get involved in helping Irish people to preserve their boglands. The Dutch Foundation was set up in 1983 to raised money and to protect endangered bogs.

The Irish Peatland Preservation Council are engaged in a campaign lobbying the government, promoting public awareness and education. The campaign is focused towards conservation of raised bogs as the threat of extinction to this unique habitat is now a reality. However, conservation should not be seen as an activity of a select committee, but part of an overall plan. It is in everybody’s best interests to preserve the bog, and try and improve on its present state. Raised bogs are becoming huge growth areas from a tourism point of view. Farmers who joined the REPS scheme are entitled to an extra 20% premium if they preserve their bog attached to their farm.

A more detailed survey (of Mullagh Bog) would need to be carried out to assess its importance from all points of view. The cost of the survey is £1,000.

Jim Smith, Rantavan, Mullagh, Co Cavan.

*DISCLAIMER: We are happy to re-publish this letter, which is by local Mullagh man Jim Smith and which was written in 1997. The view and points made in the above article are not those of the ‘The Living Bog’ LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032 or that of DAHRRGA or EU LIFE and are those of the author.

FORMATION OF THE BOG

Killyconny Bog formed when the climate conditions were moist as the glaciers and ice retreated westwards. Chalk like marl formed at the bottom of two small basins or lakes, and dead plants began forming layers of fen peat which eventually filled the lakes which gradually filled in and grew together over a low drumlin ridge. After the Fen stage the bog continued to grow – its water content 95% – to become a raised bog. Killyconny was very wet throughout at one stage, with many areas of pool and hummock formations. Drainage and cutting has affected these.

Approx 4,500 years ago, the average rainfall in Cavan decreased and this caused the bogland to dry out somewhat. This lead to the establishment of pine woodland in the area which existed for about 500 years until the climate became wetter and the bog began to grow again. These trees were found in Killyconny when turf cutting reached a certain depth.

A bog will grow by 1mm a year and with peat depth being, on average, 10m in Killyconny this dates it as being 10,000 years old.

Cutting on the bog can be traced back to pre-famine times, and it is said locally that the bog would have extended to the road that is at the edge of the bog.

Killyconny bog was a part of the Headfort estate. Lord Headfort vested the areas of Cloughbally and Fartagh in a number of Trustees in March 1921. The bog was vested with this group to be held for the benefit of landowners in the area. The areas of Leitrim, Killyconny and Ferat were divided by the Land Commission among farmers in the locality.

The history of the bog and the traditions associated with human interactions with the bog were celebrated in some style on Killyconny over the years, with ‘Mullagh Bog Day’ an annual event in the 1990’s, allowing locals and visitors alike a chance to relive a day on the bog. See Local and Community Page for more on this.

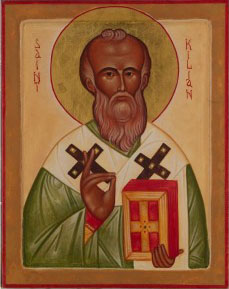

ST KILIAN

The bog has links to the story of St Kilian, who converted much of Germany to Christianity and is held in the same breath there as St Patrick is back in Ireland. A Holy Well was recorded alongside the bog in old 18th Century maps, but has since disappeared from modern maps. St Kilian’s own well is in Longfield, n the other side of Mullagh town, and on his Feast Day, July 8, crowds flock to the well for devotions.

St Kilian’s Heritage Centre was built by the local community in association with the Diocese of Würzburg in southern Germany, and opened in 1995. The centre features many relics and replicas of the saint and is one of the most popular community and tourism facilities in the north-east.

A well-stocked exhibition area opens on to a small theatre where one may view a short film on the life of St. Kilian.

The Centre also houses a craft shop packed with artistic items of interest, books and a range of locally produced work. Adjoining the craft shop is a comfortable dining area, and if the weather is with you, there is an outside picnic area.

The Centre is owned and managed by the Saint Kilian’s Heritage Trust, and came about after much hard work locally to to develop the Mullagh – Würzburg links which dates back to the 7th Century.

The area was popular with German visitors tracing their spiritual roots, and they were being catered for in a local school General Purpose room.

In 1986, the St. Kilian Committee was set up to develop the Mullagh – Würzburg links and cater for the official Würzburg tours visiting Mullagh.

St. Kilian’s Well at Longfield was restored, a limestone statue was commissioned for the grounds of St. Kilian’s Church, and in 1989 bonds were strengthened when the first official tour group from Mullagh, comprising of 90 people, visited Würzburg for the 13th Centenary of St. Kilian’s Martyrdom. Around the same time, a special St. Kilian Stamp was issued by the German and Irish Governments on the same day to mark the 13th Centenary. A limewood statue of St. Kilian, commissioned by a member of the Bavarian Parliament, Herr Christian Will, was presented to St. Kilian’s Church.

In 1991, a first class relic of St. Kilian (a bone splinter) was brought back to Mullagh by the Bishop of Würzburg amid great celebrations. It is housed in a special Reliquary provided in St. Kilian’s Church.

That same year, the plans for the St. Kilian’s Heritage Centre were drawn up and a successful application was made to the International Fund for Ireland for grant aid.

In 1992, the restoration of Teampaill Cheallaigh Cemetery was undertaken and the ruins of the Medieval Church of St. Kilian were secured and preserved. This important site is referred to in a letter in the archives of Propaganda in Rome, dated 27th September 1715.

St Kilian’s Heritage Centre in Mullagh, which attracts thousands of visitors every year since it was opened in 1995.

In 1993, work on the Heritage Centre commenced and St. Kilian’s Trust was set up to build and run it. It was completed and officially opened by President Mary Robinson on the 7th May 1995.

The main part of the exhibition was prepared in Würzburg and was donated to the centre by the Würzburg Diocese.The centre is open all-year round and for more information, check out its webpage: http://stkiliansheritagecentre.ie

‘The Living Bog’ LIFE project team will be carrying out a range of habitat restoration techniques. These will include installing new peat and plastic dams to block drainage channels which have been causing the bog to lose water. Disturbed peatland surfaces will be improved to enhance the capacity of both lobes of the bog to restore through greater hydrological connectivity, improving its ecological condition and coherence. By re-wetting the disturbed and ditched habitats, a higher water table will be created, benefitting a trange of rare bog species and in time, a more sustainable natural raised bog habitat will be restored to Killyconny Bog.

The site is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) selected for the following habitats and/or species listed on Annex I / II of the E.U. Habitats Directive (* = priority; numbers in brackets are Natura 2000 codes):

[7110] Raised Bog (Active)*

[7120] Degraded Raised Bog

Active Raised Bog (ARB) comprises areas of high bog that are wet and actively peat-forming, where the percentage cover of bog mosses (Sphagnum spp.) is high, and where some or all of the following features occur: hummocks, pools, wet flats, Sphagnum lawns, flushes and soaks.

The area of ARB at Killyconny Bog in 1994 was estimated to have been 17.0ha. However, the most recent monitoring surveys of the bog estimated the area of ARB to be 3.9ha (Fernandez et al. 2014a, b). This represents a decline of 13.8ha (81.2%) during the period 1994 – 2012. An additional survey undertaken in 2005 shows that most of this decline occurred during the period 1994-2005.

Degraded raised bog corresponds to those areas of high bog whose hydrology has been adversely affected by peat cutting, drainage and other land use activities, but which are capable of regeneration to active raised bog.

Killyconny Bog is of considerable conservation value, and has form in the restoration stakes.

Restoration works by NPWS took place at the site between 2006-10 including the blocking of some high bog drains and drains on the western and parts of the northern cutover, the grading of face banks, the installation of a length of bund on the high bog and the installation of a bund / seal on the cutover.

The latter bund/dam was installed along the western cutover boundary with adjacent agricultural land parallel to the bog road; this aims to prevent impacts on adjacent agricultural land, encourage re-wetting of larger cutover areas by locally raising water table levels and slow the rate of water loss from the bog.

Coillte also removed the 11.00ha mature conifer plantation (mainly lodgepole pine ) on the southwest cutover of the southern lobe and drains were blocked as part of a previous LIFE Nature project (LIFE04 NAT/IE/000121).

The exact details of our restoration works will be revealed soon, but at present we are looking at installing and maintaining over 1,000 dams, mainly peat with some plastic dams where machinery cannot reach. Several thousand metres of drains will be blocked on both the high bog and the cutover.

A long period of time (i.e. over 30 years) may be needed after appropriate restoration works are undertaken on the cutover areas for the habitat to develop. Restoration works along the western cutover of Killyconny Bog SAC indicated the occurrence of pioneer ‘active raised bog’ vegetation 8 years after these were undertaken.

Information signs and additional public access is being looked at, particularly as the bog has such a high amenity value. Details will be here in time.

The LIFE team are currently undertaking an extensive survey of Killyconny Bog SAC and we will present the results here soon.

The bog has been modified in the past through drainage and cutting which has resulted in the drying out of the surface and a consequent loss of species. The total area of uncut high bog is 83.04ha while the remaining 108.18ha is mostly cutover bog resulting from previous turf- cutting, which has completely ceased on this bog. Despite the loss of species, both areas are still teeming with life and restoration will add a more sustainable, natural habitat. The information below is gleamed from previous site survey work, and paints an interesting picture of a unique living bog.

FLORA OF KILLYCONNY BOG

Killyconny Bog supports the full complement of plant species typically associated with a midland ridge basin raised bog.

Much of Killyconny Bog is very wet and there are many areas of pool and hummock formation. The pools support the bog moss Sphagnum cuspidatum, and a good growth of algae in summer. Wet areas about the pools support other Sphagnum mosses such as S. magellanicum, while S. papillosum, S. fuscum, S. capillifolium and Hypnum cupressiforme are important components of hummocks. A range of vascular plants typical of raised bogs are found, including cottongrasses (Eriophorum angustifolium and E. vaginatum), heathers (Calluna vulgaris and Erica tetralix), Bog Asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum) and White Beak-sedge (Rhynchospora alba). Also occurring on the site is Bog-rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) which is found almost exclusively on midlands raised bogs and which is rare in north-east Ireland.

While the surface of the bog is generally homogeneous some higher areas with dense tussocks of Hare’s-tail Cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum) are found; these provide shelter for Hares. There are also lines of water movement, shown by the occurrence of Common Sedge (Carex nigra) and Soft Rush (Juncus effusus).

The most recent survey from 2014 indicates that central ecotope is found on Killyconny Bog at only one location and sub-central ecotope at six locations (Fernandez et al. 2014a, b). The central ecotope occurs in a depressed area featuring hummocks, hollows, and pools (34-50%).

Sphagnum cover ranges from 51-75%, and consists of Sphagnum capillifolium, S. austinii, and S. fuscum, S. magellanicum and S. papillosum hummocks and S. cuspidatum in pools along with Drosera anglica. The cover of Sphagnum cuspidatum is patchy in some pools that appear to be suffering from desiccation in places.

Sub-central ecotope areas consist of low Sphagnum capillifolium hummocks and hollows with S. cuspidatum in places. Overall Sphagnum cover is greater than 50%, and reaches 75% in places. Other Sphagnum species include S. papillosum, S. fuscum, S. magellanicum, S. tenellum, and S. subnitens. Sub-central ecotope becomes wetter in other sections where pools dominated by S. cuspidatum are found, but are rather small and contain high Narthecium ossifragum and Rhynchospora alba cover.

Non-active ecotopes present on the bog include sub-marginal, marginal, and face bank ecotope. Although some of the sub-marginal areas have a relatively well-developed raised bog flora, they are affected by water loss to varying degrees, and are usually devoid of permanent pools.

The sub-marginal ecotope features the most developed microtopography, with higher presence of hummocks and hollows (frequently dominated by Narthecium ossifragum and only occasionally Sphagnum cuspidatum and S. tenellum). Sphagnum covers up to 33% of the ground and mostly consists of S. capillifolium. However, Sphagnum papillosum, S. magellanicum, S. tenellum and S. subnitens are also found forming hummocks and S. cuspidatum in hollows. The most widespread sub-marginal ecotope vegetation type on the site is characterised by dominant Calluna vulgaris, Erica tetralix and Narthecium ossifragum. Eriophorum vaginatum, E. angustifolium, Rhynchospora alba, and Trichophorum germanicum are also common at various degrees of coverage.

Marginal ecotope is slightly drier than sub-marginal ecotope and mainly occurs as a narrow band near the margins of the high bog. Microtopography consists of Heather Calluna vulgaris hummocks, low Sphagnum hummocks, flats and very occasionally hollows. The Sphagnum cover is even lower here than in the sub-marginal ecotope (<10%) and the vegetation is characterised by higher cover of Narthecium ossifragum, Trichophorum germanicum, and Calluna vulgaris.

Face bank ecotope is characterised by firm ground, tall Calluna vulgaris, poor Sphagnum cover and a flat microtopography. This ecotope is found at the edges of the high bog.

Peat cutting is no longer carried out at the site. Rhynchosporion vegetation is widespread on Killyconny Bog. It is found in both ARB and DRB, but tends to be best developed and most stable in the wettest areas of ARB. In these areas, the Rhynchosporion vegetation occurs along pool edges and on lawns underlain by deep, wet and quaking peat. Typical plant species include Rhynchospora alba, Sphagnum cuspidatum, S. magellanicum, S. papillosum, Drosera anglica, and Eriophorum angustifolium.

Rhynchospora alba was also found in more degraded situations, but always associated with wet features such as hollows.

The north and west cutover includes areas that are dominated by embryonic bog vegetation with low hummocks of Sphagnum palustre and extensive depressions dominated by Sphagnum cuspidatum and Eriophorum angustifolium.

The degraded bog is largely restricted to the margins of the high bog areas where drainage effects are most pronounced. In general, much of the degraded bog surface is dominated by Heather (Calluna vulgaris) and Deergrass (Scirpus cespitosus) with Bog Asphodel and White Beak-sedge dominating in the wetter areas. Typically these species form mono-dominant, species-poor stands. In the driest areas of degraded raised bog there is some colonisation by plant species such as Downy Birch (Betula pubescens) and Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum).

The uncut high bog area is surrounded by extensive cutover surfaces and a portion of this cutover has been planted with conifers. A previous LIFE project removed a large amount of conifers which saw an immediate increase in the amount of ARB.

FAUNA OF KILLYCONNY BOG

Irish hare (Lepus timidus hibernicus) and pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus) have been recorded on the high bog. The common frog (Rana temporaria) also occurs.

Bird species found on the bog include curlew (Numenius arquata), snipe (Gallinago gallinago), skylark (Alauda arvensis), meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis), and sometime kestrel (Falco tinnunculus).

The long-eared owl (Asio otus) has been observed on site hunting over it for prey items such as beetles, Pygmy Shrew and common frog. The sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) has also been observed in the past. However, there were no curlew sightings on the bog in recent years

Foxes and badgers have discovered in larger hummocks, and insect-wise the bog – like all raised bogs – is alive and well with bog caterpillars, moths and various butterflies seen, as are dragonflies, damselflies and various water skaters, water beetles, water boatment, slugs and spiders.

As detailed in our Local, Community and History pages, local man John K Smyth was written about the bog teeming with life in the 1950’s and 1960’s, with the Curlew in particular being very prolific. Pheasants, Red Grouse, Red Partridge, Snipe, Pied Wagtail, Moorhens, Cuckoo, Reed Warblers, Woodcock, Kingfisher and Barn Owls were all common and are detailed in John’s bog memory piece.

The LIFE team will have an up-to-date fauna report here soon.

Killyconny Bog SAC (also known locally as Cloghbally Bog and Mullagh Bog) is a 191 hectare raised bog just outside the historic Cavan town of Mullagh. It is an important bog which has played a big role in the local community for generations, and its location is unique as not only is it the most northern project site, but it is the only LIFE project site to share two counties: Cavan and Meath. It is said that the Apostle of Franconia, St Kilian, had connections to this impressive bog.

The bog has been at the centre of the local community for many decades, and it received widespread attention in the 1990’s when the local community came together to host three ‘Day on the Bog‘ festivals.

As the crow flies, the bog is approximately half-way between Virginia and Kells on the Cavan/Meath border. The bog was historically divided into five different townlands: Cloughbally; Fartagh; Leitrim; Killyconny; and Fegat.

The hollows between the hills of this beautiful part of the country fostered many a raised bog, but today there are very few raised bogs left in the north-east region and Killyconny Bog is the best developed of what remains. It is unusual as it developed with two lobes formed on adjacent ancient lakes. As the bogs rose side by side over thousands of years, they spilled over towards each other. Today they are joined by a narrow strip of bog, with the bog an odd ‘figure of 8’ shape.

Though some marginal drainage and cutting has taken place and there is subsidence on the margins, the central parts of the bog are relatively intact as little drainage was ever done on the ‘high bog’. Some restoration works took part on this bog in the past (including LIFE project LIFE04 NAT/IE/000121) with favourable results. Overall, there are good restoration prospects on Killyconny and the project aims to almost treble the existing areas of Active Raised Bog (ARB) on the high bog through a restoration programme aimed at raising the water table.

Water retention on Killyconny Bog, carried out as part of a previous restoration project on a section of the raised bog.

This bog is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) selected for Active Raised Bogs 7110 and Degraded Raised Bog 7120 – habitats that are listed on Annex I of the EU Habitats Directive (992/43/EEC), where Active Raised Bogs 7110 is further ranked as a “priority” habitat. Depressions on peat substrates of the Rhynchosporion (EU code 7150) are also found here.

There is a tremendous community spirit in the environs of the bog. Killyconny has had a high amenity value for many years, from the ‘Mullagh Bog Day’ festivals of the 1990’s to present day walking routes around the bog. There are many fond memories locally of working on the bog in the hey-day of peat extraction by hand (see HISTORY page).

Mullagh town is one of Ireland’s hidden gems with enviable heritage and tourism assets. Every year thousands of tourists visit the area to celebrate the town’s links to St Kilian, the 7th and 8th Century Apostle of Franconia and Irish Missionary Bishop, who was born close to Killyconny Bog. The St Kilian’s Heritage Centre in the town is at the heart of everything that happens in the area, and is an ideal starting point to learn more about Killyconny Bog and this the surrounding area.

This page belongs to the communities surrounding Garriskil Bog SAC. Whether you are a local community or heritage group, a men’s shed, a sporting organisation or any group in the surrounding hinterland of the bog, this section of the Garriskil site is for you.

Stories and history from the area is currently being compiled by our project team.

If you have a community web presence, or newsletter or information sheet you’d like to see reach a wider audience, don’t hesitate to let them know and it will go up on this site.

We will also link to interesting people and events in the areas surrounding this important raised bog. We want to celebrate the past, present and future of this area.

The culture and traditions associated with the people, communities and bogs in Westmeath deserve to reach a wider audience and our Public Awareness Manager is keen for this aspect of our bogs to be celebrated just as much as the conservation and restoration of raised bogs.

The area surrounding Garriskil Bog is alive and well, with many active groups, including:

STREETE PARISH PARK AND COMMUNITY CENTRE/SPORTS COMPLEX

Streete Community Centre is a hive of Activity all year round, and the hall is open to local groups, sports organisations and more.

The main hall seating capacity 800 and has two viewing balconies. There is a movable stage and amplification is available onsite. The hall has hosted many events in the past, from dances to concerts to farmers markets to conferences and meetings. There is a separate meeting room available also, and there are fully equipped office facilities including broadband, photocopying etc. There is a fully equipped kitchen and a bar can be provided if necessary. The Community Centre is also a Sports Complex and features two changing rooms with shower facilities, an International Size Basketball Court complete with electronic scoring board. The venue can be used for Indoor Soccer, Indoor Bowls (with up to 11 mats available) and can be transformed into 4 Badminton or Volleyball Courts. Outside is a full-size Gaelic Pitch and facilities for soccer and Tag Rugby. There is a Children’s Play Area Provided by the Parents Group.

For more info, see the FACEBOOK page.

STREET PARISH PARK VINTAGE CLUB

The vintage club in Streete is one of the busiest in the country, and every July they host one of Ireland’s biggest vintage shows in the Parish Park. The show is a celebration of all vehicles vintage, with classic cars, bikes, trucks and working vehicles aplenty and, of course, Ireland’s agricultural heritage features strongly with some mighty machines. The day is also a great family fun day, with entertainment and many exhibitions and areas for the family.

In 2015, the Vintage Club was chosen to host the All Ireland Vintage Show. It was the second time in 10 years they hosted the massive event. The group are active on FACEBOOK

BOHERQUILL RAMBLERS

Formed in 2000, the north Westmeath walking group are one of the biggest in the midlands. They meet every Sunday and have a busy schedule of walks all year round. They walk all over the country, host local walking festivals and many of their walks are for charity, including a popular St Stephen’s morning walk at nearby Mullaghmeen Forest, Ireland’s largest planted beech forest.

The group are proud of their North Westmeath roots, saying: “We know we live in a beautiful unexplored part of the Midlands in North Westmeath, which we are proud to share with like-minded groups who like rambling. We may not have mountains but we have Bog, River, Canal, Forest and much more to offer.”

For more, check out their WEBSITE

Garriskil Bog is the best-preserved piece of a once huge raised bog system of river floodplain bogs which developed where the River Inny enters and leaves Lough Derravarragh, not too far from the town of Mullingar. Most of these bogs are now affected by human interference, with many of them industrially harvested or strip-mined, which makes Garriskill an exceptional and all-too-rare reminder of a once common landscape in this part of the country.

Garriskil Bog SAC is the (relatively) intact bog left of centre in this Bing Maps view of this part of North Westmeath

The bog was purchased by the Dept of Finance in 1989 alongside Ballykenny/Fisherstown Bog. At the time, they bought 203 hectares between the two sites, and also purchased 506 hectares of blanket bog at the Sally Gap. Speaking in Dail Éireann in 1990, then Finance Minister Albert Reynolds (who hailed from nearby Longford) said the government had a raised bog conservation target of 10,000 hectares.

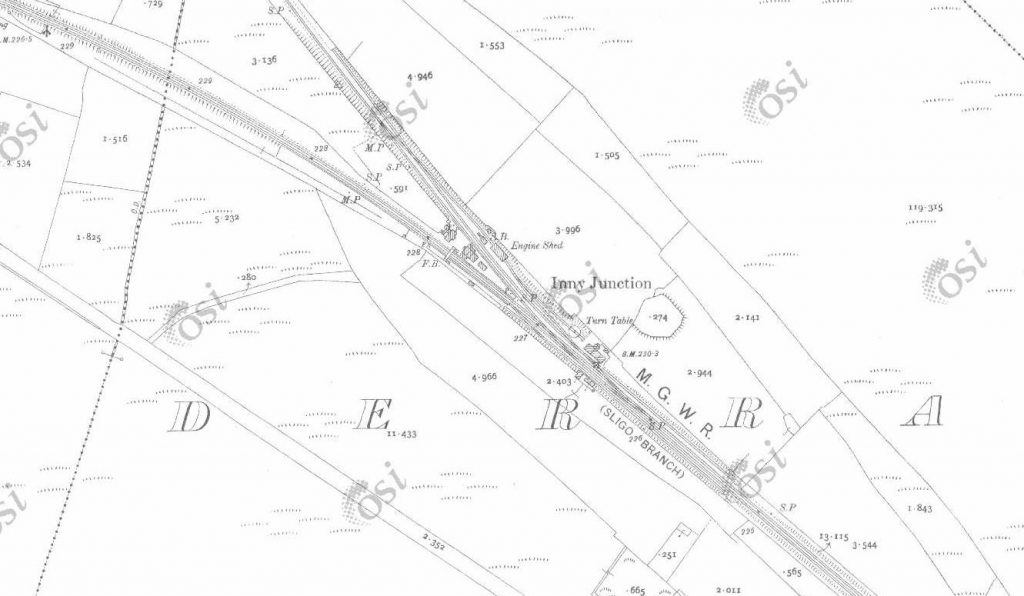

Turf-cutting on this raised bog can be traced back to long before the first records of 1840, and locals recounted stories of turf being brought to Mullingar railway station for distribution to the hospital in Mullingar – most likely St Loman’s Psychiatric Hospital. How did they bring the turf by rail? Well, the answer lies with one of Ireland’s most unique train stations…

Inny Junction – Ireland’s bog train station with no roads

Right beside Garriskil Bog is the site of Inny Junction train station which, at one stage, was famously the only train station in Ireland and the entire British Isles not be serviced by a road! (this startling fact was once the subject of a question on TV’s ‘Mastermind’). With the nearest towns and villages a few miles away, it was literally in the middle of nowhere! The station was where the Sligo – Dublin line split into a Mullingar – Cavan branch.

Much of the bog to the north is bordered Dublin-Sligo railway line, which used to be known locally as ‘the Principle Line’. If you’re ever on the train from Dublin to Sligo (or vice versa) today you can’t miss the bog. If heading towards Sligo, it is just a few miles outside Mullingar after you pass Lough Owel, and if heading to Dublin it is halfway between Edgeworthstown and Mullingar. As of late 2017, 20 passenger trains daily pass through the bog, bringing thousands of people from east to west and vice-versa. This makes Garriskil perhaps the most viewed bog in the country! The full extent of Garriskil Bog is visible from one side of the train, with turf cutting and harvesting on the other side.

A Sligo-Dublin train cutting through Garriskil Bog SAC, just outside Mullingar. Photo by Living Bog ecologist John Derwin.