MARY WARD and FERBANE BOG

Mary Ward was born Mary King in Ballylin near present-day Ferbane, on 27 April 1827, the youngest child of the Reverend Henry King and his wife Harriette. She and her sisters were educated at home, as were most girls at the time. However, her education was slightly different from the norm because she was of a renowned scientific family. She was interested in nature from an early age, and by the time she was three years old she was collecting insects, most of them out on Ferbane Bog!

Ward also drew insects, and the astronomer James South observed her doing so one day. She was using a magnifying glass to see the tiny details, and her drawing so impressed him that he immediately persuaded her father to buy her a microscope. This was the beginning of a lifelong passion. She began to read everything she could find about microscopy, and taught herself until she had an expert knowledge. She made her own slides from slivers of ivory, as glass was difficult to obtain, and prepared her own specimens. The physicist David Brewster asked her to make his microscope specimens, and used her drawings in many of his books and articles.

Shockingly, at the time, Universities and most societies would not accept women, but Ward obtained information any way she could. She wrote frequently to scientists, asking them about papers they had published. During 1848, Parsons was made president of the Royal Society, and visits to his London home meant that she met many scientists.[4]

She was one of only three women on the mailing list for the Royal Astronomical Society (the others were Queen Victoria and Mary Somerville.

She illustrated her six books and articles herself, as well as many books and papers by other scientists.

She was a pre-eminent scientist, and it is a miracle that Ferbane Bog, in the shadow of a turf burning power station, survived at all. it is the site where she made many of her discoveries, and we hope to encourage young scientists to follow in her trail-blazing footsteps.

We were thrilled in 2018 to have been part of an immersive show devised by photographer Tina Claffey and artist Caroline Conway called ‘Mary Ward’s World of Wonder‘. Book the show today for your school, college or community!

Info HERE

FORMATION OF FERBANE BOG

Ferbane Bog SAC is estimated to be over 10,000 years old, occurring in a basin, predominantly underlain by limestone, with clay-rich tills above the bedrock. It has a discreet, raised dome and is a unique site in terms of this LIFE project, due to its proximity to the town of Ferbane. It is also just a short distance from another of our project sites: Moyclare SAC.

The raised bog here began to develop in the basin lake in which anaerobic conditions occurred. Complete decomposition of plant material was prevented. In time this un-decomposed plant material formed a thick layer of peat that rose towards the surface of the lake. Eventually the surface peat was invaded by sedges to form a fen. The fen peat layer thickened so that the roots of plants growing on the surface were no longer in contact with the calcium-rich groundwater. The only source of minerals for plants was now rainwater, which is very poor in minerals. Raised bog species, such as Sphagnum mosses begin to invade and eventually the fen becomes a raised bog.

The surface of a raised bog consists of a soft living carpet of vegetation, which floats on a material which is nearly all water. By weight, a raised bog may be up to 98% water and only 2% solid matter. This volume of water is held within dead Sphagnum moss fragments.

Raised bogs consist of two hydrological layers: the upper, very thin layer, known as the acrotelm;, is usually less than 50cm deep, and consists of living stems of Sphagnum mosses, recently dead plant material and water. The acrotelm has high permeability to water near to the surface, but becomes more impermeable with depth as the peat becomes more consolidated and decomposed (humified). Water movement and fluctuations mean that conditions in the acrotelm remain largely aerobic and it is here that microbial activity is strongest. The acrotelm is critical to the normal development and functioning of a raised bog.

Below this is a very much thicker bulk of peat, known as the catotelm, where individual plant stems have collapsed under the weight of mosses above them to produce an amorphous, dark mass of Sphagnum; fragments. Catotelm peat is typically well consolidated and often strongly humified. It is permanently saturated with water. Water movement through this amorphous peat is very slow, typically less than a meter a day. This is where most of the rain water is stored.

Deep drainage associated with turf cutting means Ferbane has suffered in the past, with the south and east traversed by drains.

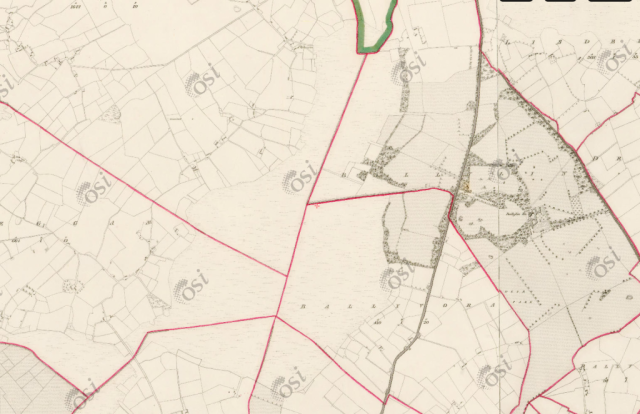

In the past, peat cutting to the north and east of the site was significant. There is a series of lines drawn on the 1910, 6” map, which correspond with old turbary rights. More recent peat extraction is evidenced by abandoned sausage machine cut peat, at the north and south of the site (Kelly et al., 1995). The bog was selected for development as a peat source by Bord na Mona in 1983. This has not occurred and the site was subsequently transferred to National Parks and Wildlife Service ownership in 1996. The majority of the bog is in public ownership.

The 1910, 6” map shows planted forestry to the east of the site. This was probably predominantly Scots Pine. This has most likely been felled and regenerated over the years, with the invasion ofother species such as Birch.

FERBANE POWER & A JOB WITH ‘THE BORD’

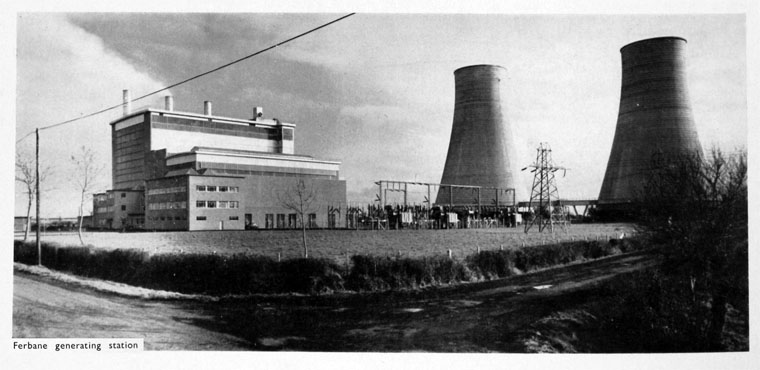

Bogs in this part of the country – and in particular the once common raised bogs – are synonymous with the fuel industry. Ferbane owes an awful lot to the now demolished power station, which employed thousands in the five decades it was operational. It was the first ever milled peat fired power station to be built and commissioned in Ireland, the first in the world outside the former U.S.S.R.

Construction started in 1953 and it was commissioned by the Electrical Supply Board (E.S.B.) in 1957 with the first development of 60,000 kilowatts. The second stage of development of a further 30,000 kilowatts commenced in June 1961, and was commissioned in January 1964. This brought the total capacity of the Station to 90,000 kilowatts, capable of producing about 400 million units of electricity a year.

At its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, the station burned 2,000 tonnes of peat daily, producing about 2 million units of electricity daily when its four units were at full load. The milled peat was brought in by train on narrow gauge lines, mainly from the Lough Boora complexes. Each unit consisted of a boiler, a turbine, a generator and a transformer. Boilers 1, 2 and 3 (first development) each produced 100 tons steam per hour, at a pressure of 30 kg/cm2 and temperature 440°C to drive Brown Boveri 20 MW turbines and directly coupled generators at 3,000 revs per minute. The 4th unit (2nd development) had a 130 ton/hr boiler giving steam at a pressure of 63 kg/cm2 and at a temperature of 510°C which drove a 30 MW Parsons Turbine and directly coupled Generator at 3,000 revs per minute. The electricity was generated at 10,000 volts and transformed to 110,000 volts for transmission into the national grid.

(Film from the Huntley Film Archives)

However, the station was getting old and by the mid 1990’s the obsolete station was contributing little to the National Grid. Closure was recommended for 1998. However, its closure was not without its controversy, as the Irish Independent reported in 1998 and the Irish Times reported in 2001. It had not provided power for almost three years before it was finally closed. Demolition took place in 2003, and the ESB have recorded its demolition HERE.

Had Ferbane Power Station survived into the 21st century, the destiny of Ferbane Bog SAC might have been different and may well have involved chimney stacks. However, the bog

There can be no denying that towns like Ferbane have suffered with the closure of the power plants, mechanisation and Bord na Móna’s long, slow exit from peat extraction. As journalist Rodney Farry outlines HERE in an Irish Times feature, a job with Bord na Móna was ‘it’: “For young men in Ferbane and the surrounding villages, landing a permanent position with “the bord”, as locals call it, brought job security and a guaranteed pension, rare in 1950s Ireland.”

FERBANE TRAIN STATION

Once-upon-a-time, Ferbane was a key stop on the former 17 mile branch from Clara to Banagher, constructed by the Clara and Banagher Railway and opened in 1884 (after a protracted construction as a large section went through bog). Clara-Banagher started out as an independent line but ran out of money a few times and was eventually taken over by the Great Southern and Western Railway, linking Ferbane to all the major lines and destinations.

The line lost its passenger service becoming freight only in 1947. The line remained in use for goods and occasional special services until it was closed in a tranche of branch closures all over the country in 1963.

A child plays on the platform as a CIE goods train bound for Banagher departs from Ferbane Train Station in 1960. (Pic: Roger Joanes/Ciaran Cooney/Eiretrains)

And a little over three years later: Ferbane Railway Station in 1964, with the line in the process of being dismantled. (Pic: National Library of Ireland.)

The former station in Ferbane remains visible to this day, with the station building, a Victorian structure built in 1884, surviving, along with the goods shed. The station is now reused, housing offices for the local Council. Architecturally, the design is both simple and functional, adorned by few enrichments like bargeboards to the gables, cast-iron rainwater goods and stepped brick cornice to eaves. Like a lot of midlands stations (and others on the Banagher branch), it was a combination of a single and two-storey building.

The former Ferbane Station today, with the goods shed (now a Council storage shed) to the rear. No train line remains.

Office space: the former Ferbane Train Station

However, the platform and road overbridge (which carried the N62) is long since demolished, and most of the line itself is long gone.

The branch left the Portarlington-Athlone line at Clara and Banagher Junction, just outside the town. There was also a station at Belmont.

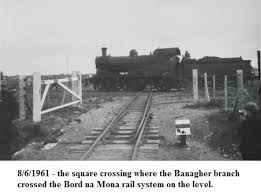

An unusual feature of the line was at Lemanaghan Bog, east of Ferbane town, where there was a unique flat level crossing with the narrow gauge Bord na Móna system serving the power station. All that’s left of this today is the remains of a gate post. For more, see the Eire Trains site HERE

COOLE CASTLE

Sir John MaCoghlan built Coole Castle on the banks of the River Brosna in 1575. It was the last of the MacCoghlan castles to be built. He erected it as a present to his second wife Sabina O’Dallachain. Formerly there was a mural slab in the castle with a Latin inscription translated in English as ““This tower was built by the energy of Sir John MacCoghlan, K.T. chief of this Sept at the proper cost of Sabina O’Dallachain on the condition that she should have it for her lifetime and afterwards each of her sons according to their seniority”

The whereabouts of the mural is unknown at present. In his will in 1590 Sir John left Coole Castle to his widow. Over the fireplace, in its original location, in the topmost room of the castle is a plaque written in Middle Irish which reads:

“SEAGHA (n) MAC (c) OCHL (ain) DO TINDSCAIN O SEO SUAS 1575” (“Sean Mac Cochlan began (this building) from this (date) 1575”)

Coole Castle, Ferbane.

Coole Castle, Ferbane.

LIFE+ Nature and Biodiversity

The LIFE programme is the EU’s funding instrument supporting environmental, nature conservation and climate action projects through the EU. The general objective of LIFE is to contribute to the implementation, updating and development of EU environmental policy and legislation by co-financing pilot or demonstration projects with European added value.

LIFE began in 1992 and to date there have been five phases of the programme (LIFE I: 1992-1995, LIFE II: 1996-1999, LIFE III: 2000-2006, LIFE+: 2007-2013 and LIFE+ 2014 – 2020).In the first four phases, LIFE has co-financed some 3,954 projects across the EU, contributing approximately €3.1 billion to the protection of the environment.

The adoption of the Single European Act in 1986, which for the first time gave EU environmental policy a firm treaty basis, along with the Fifth Environment Action Programme, approved in 1993, really opened the door for the LIFE funding mechanism. These two developments set the pace of environmental reform for the next decade and the LIFE programme was one of the EU’s essential environmental tools.

The Living Bog (LIFE14 NAT/IE/000032) is part of the fifth phase of funding. The LIFE 2014-2020 Regulation (EC) No 1293/2013 was published in the Official Journal L 347/185 of 20 December 2013. The Regulation establishes the Environment and Climate Action sub-programmes of the LIFE Programme for the funding period, 2014–2020. The budget for the period is set at €3.4 billion.

The LIFE programme will contribute to sustainable development and to the achievement of the objectives and targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy, the 7th Union Environmental Action Programme and other relevant EU environment and climate strategies and plans.

The ‘Environment’ strand of the new programme covers three priority areas: environment and resource efficiency; nature and biodiversity; and environmental governance and information. The ‘Climate Action’ strand covers climate change mitigation; climate change adaptation; and climate governance and information.

The programme also consists of a new category of projects, jointly funded integrated projects, which will operate on a large territorial scale. These projects will aim to implement environmental and climate policy and to better integrate such policy aims into other policy areas.

The new regulation also establishes eligibility and the criteria for awards as well as a basis for selecting projects. The programme is open to the participation of third countries and provides for activities outside the EU. It also provides a framework for cooperation with international organisations.

In June 2017, the European Commission will carry out an external and independent mid-term evaluation report and by December 2023 it will complete an ex-post evaluation report covering the implementation and results of the LIFE Programme.

LIFE+ Nature & Biodiversity co-finances best practice or demonstration projects that contribute to the implementation of the Birds Directive (79/409/EEC) and the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) and the Natura 2000 network. It also co-finances innovative or demonstration projects contributing to the implementation of the objective of Commission Communication (COM (2006) 216 final) on “Halting the loss of biodiversity by 2010 – and beyond”

Natura 2000

Natura 2000 is a European network of important ecological sites. It is an EU wide network of nature protection areas established under the 1992 Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC). It is comprised of Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) designated by Member States under the Habitats Directive, and also incorporates Special Protection Areas (SPAs) designated under the 1979 Birds Directive (79/409/EEC). The aim of the network is to assure the long-term survival of Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats. The establishment of this network of protected areas also fulfills a Community obligation under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

The Living Bog project sites are all SAC’s and Natura 2000 sites.

A selection of other LIFE Projects in Ireland:

AranLIFE

BurrenLIFE

KerryLIFE

MulkearLIFE

DuhallowLIFE

Details of all LIFE Programme projects in Ireland and elsewhere can be found at: www.ec.europa.eu

The Living Bog is a partnership project between the EU LIFE Programme and the Department of Housing, Heritage and Local Government’s National Parks and Wildlife Service. Overall, the project was managed – and the project actions are being implemented – by a five-person Project Team based in Mullingar, in the heart of the Irish midlands. The Project Team are under the direction of a larger Project Steering Group, representing Irish Govt, local communities, NGOs and other stakeholders. Additional expert advice on implementing the project actions is available through the Stakeholder Advisory Group and Technical Advisory Group.

Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

The National Parks and Wildlife Service at the Department of Housing, Heritage and Local Government under Minister of State Malcolm Noonan TD is the Coordinating Beneficiary on the project and provides the legislative and policy framework for the conservation of nature and biodiversity in Ireland, and oversees its implementation.

The Department will:

• Coordinate delivery of the Living Bog contract and support the technical and administrative processes;

• To secure the conservation of a representative range of ecosystems and maintain and enhance populations of flora and fauna in Ireland;

• To designate and manage Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in accordance with the EU Habitats and Birds Directives;

• To designate and advise on the protection of Natural Heritage Areas (NHAs) having particular regard to the need to consult with interested parties;

• To make the necessary arrangements for the implementation of National and EU legislation and policies and for the ratification and implementation of the range of international Conventions and Agreements relating to the natural heritage;

• To manage, maintain and develop State-owned National Parks and Nature Reserves;

• To control activities that may harm or threaten habitats or species;

• To develop knowledge by research;

• To survey and monitor habitats and species of conservation value;

• To disseminate information and increase awareness of natural heritage;

• To provide advice on natural heritage and biodiversity to other authorities.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service has extensive experience in the area of the proposed project, and has also lead or participated in a considerable number of previous LIFE projects, including two previous bog restoration projects undertaken by the Irish Forestry Service, Coillte. (LIFE 04 NAT/IE/000121 and LIFE02 NAT/IRL/8490)

Further information can be found www.housing.gov.ie or www.npws.ie

Project Steering Group

- Details coming soon

Stakeholder Advisory Group

- Details coming soon.

This page belongs to the communities surrounding Sharavogue Bog. Whether you are a local heritage group, a men’s shed, drama group, arts group, school or a sporting organisation, this section of the Living Bog site is for you.

If you have any interesting stories, photos, information or anything concerning Sharavogue and its environs, please email peatlandsmanagement@npws.gov.ie

This is an area of Ireland and the midlands where even the smallest local story or photograph could make a big impact nationally and globally.

Stories of days on the bog, or days on land surrounding the bog are part of our collective Irish history, but much of what we know we take for granted, and what may be ordinary to you or I might be EXTRAORDINARY to someone else. Even the most ordinary tale of transporting turf will have resonance for others, so let us know. Of if you know anyone with a story to tell, let us know

Whilst this project is about restoring a number of raised bogs, we want to celebrate everything to do with bogs, past present and future, so if you have stories and memories of days on the bog, please let us know and we’ll share them to the one man and his dog who will turn up to listen to them.

At present there are NO visitor facilities at Sharavogue Bog SAC. Most of the bog is in private ownership so unsupervised visits are not advised, encouraged or allowed.

The bog is wet and dangerous, a constantly shifting mass of peat full of bog pools, deep and deceiving Sphagnum lawns and more dangers than you can shake a stick at.

The LIFE project will host open days on Sharavogue over the duration of the project, and local community events and and guided tours will take place on the bog in the near future.

Information on these will be posted here, on the events page and on the Local and Community Page. You can also keep up to date on any events on Sharavogue Bog and our other project sites by following and liking our social media. The Living Bog FACEBOOK page is updated daily, as is the project TWITTER page

Should you wish to visit Sharavogue Bog for research purposes, you can contact the NPWS via www.npws.ie

There is plenty to do and plenty to see in the area close to Sharavogue Bog, and the hidden gem that is Birr is only a short distance away.

BIRR

Formerly known as Parsonstown, Birr is one of the most historic and picturesque towns in Ireland – a jewel in the midlands – and is well worth a visit.

Birr is a designated Heritage Town with a carefully preserved Georgian heritage, of wide streets and elegant buildings. It is an ideal centre for touring the midlands, with everything from Birr Castle to the ‘Leviathan of Parsonstown’ (an astronomical telescope – at one stage the world’s biggest) to the Georgian Mills to the Workhouse to the parks along the River Camcor vying to keep you in the town. The first ever All-Ireland Hurling Final was played at Hoare’s Field in Birr (now a Tesco site) in 1888 between Tipperary and Galway.

Birr Castle Gardens and Science Centre

Birr Castle has become one of Ireland’s must-see attractions in recent years. As Birr Castle Gardens and Science Centre, it is a place where history, nature and science collide.

Allow yourself plenty of time to explore Birr Castle’s spectacular Gardens and fascinating Science Centre. For many years the Parsons family have invited the public to explore one of the most extraordinary places in Ireland. Created over generations it is an environmental and scientific time capsule, and if you are on the ‘Ireland’s Ancient East’ tour, it is a place you cannot miss.

Regardless of the time of year you visit, the award winning gardens won’t disappoint with their rare and exotic plants. The gardens are home to an abundance of rare plants, collected by the Earls of Rosse on their travels around the world over the last 150 years. Within the 50 hectares you will find the world’s tallest box hedges, over 40 champion trees, over 2000 species of plant as well as rivers, lake and waterfalls.

At the Science Centre, you travel back to the time when Birr Castle was a hub of scientific discovery and innovation, the third Earl was building the great telescope and his wife Mary was practising her photography. Later, their son Charles Parsons was inventing the steam turbine, which changed the face of seafaring and led to the invention of the jet engine. The interactive centre reveals the wonders of early photography, engineering and astronomy with a special emphasis on the brilliant design and assembly of the world famous Great Telescope.

The Great Telescope, designed and built by the third Earl of Rosse in the early 1840s, it was the largest telescope in the world. With this telescope, he discovered the spiral nature of some of the galaxies, and from 1845-1914, anyone wishing to witness this phenomenon had to come to Birr. This ‘leviathan’ as it is named, remains in the centre of the Demesne as Ireland’s greatest scientific wonder and represents a masterpiece of human creative genius – you can’t miss it!

Of course, kids also love the Castle. All you budding knights and princesses will find themselves lost in a world of imagination in the epic Treehouse Adventure Area. The playground features Ireland’s largest treehouse along with a bouncy pillow, sandpits and a hobbit hut. And while they’re busy in the Treehouse Adventure area, you deserve a coffee and a browse around the gift shop – and everyone’s happy!

Birr Castle Treehouse Adventure Area

Birr Vintage Week

In July/early August the town comes alive as it celebrates our collective past with the highly-rated Birr Vintage Week, one of the great Irish town festivals. 2018 will be the 50th year of the Festival and the celebrations planned for the 50th anniversary should be spectacular!

For more, check out:

BIRR VINTAGE WEEK AND ARTS FESTIVAL

BIRR HISTORICAL SOCIETY

BIRR CASTLE

BIRR THEATRE & ARTS CENTRE

BIRR PHOTOGRAPHY GROUP

Offaly County Council have an extensive website www.offaly.ie which features excellent Heritage and Arts and Culture coverage.

TOURISM INFO

The history of Sharavogue Bog is long and varied taking in the Ice Age, peat extraction, famine, rail disasters and much more besides, but it is the 1990’s intervention of two local farmers, Mr Liam Egan and Mr Patrick Headon, after drainage channels were sliced across the high bog which has ensured Sharavogue will remain as a living bog for the enjoyment of generations to come. In fact, the most recent episode in its history is probably the most important.

The efforts made by Mssrs Egan and Headon in preserving the bog in the 1990’s have been internationally recognised, as the following 1998 report from the Irish Times illustrates:

Offaly farmers win award for saving raised bog

“A major conservation award has been presented to two farmers from Birr, Co Offaly, for saving a raised bog at Sharavogue at Ballyegan.

Mr Liam Egan and his neighbour, Mr Patrick Headon, were recently given a special award by the Dutch Foundation for Conservation of Irish Bogs, in the Netherlands.

Sharavogue Bog is one of the best remaining examples of raised bog in Ireland as it contains pristine high bog but also preserves important relics of the original lagg-zone: the transition zone between bog and the surrounding landscape.

Such lagg-zones are extremely rare in the Irish and international context as they were lost in virtually every remaining bog site as a result of marginal drainage and peat cutting.

Because of this Sharavogue is listed as a Scientific Area of Conservation under the EU Habitat’s directive.

This week, Mr Egan, who is very active in the Irish Farmers’ Association and is chairman of its animal health committee, said he was delighted with the award.

The bog came under threat some years ago when an effort was made to develop it for peat extraction, he explained, adding that he and his neighbour, Mr Headon, a stud farm owner, took out an injunction against the developer to stop the drainage and destruction of the site.

“We began a search and found the original owner of the bog in England, a descendant of the local landowner, and we purchased the bog from him. We were then sued by the developer for loss of earnings and it dragged on for years and cost both of us a lot of money but in the end we won out and the bog has been saved,” he said.

They later entered into a management agreement with Duchas, the heritage service, which is currently looking at repairing the bog.

“I just love the bog. I’m delighted that it has been protected and the area around saved from the exploitation of the peat with all the problems that creates,” he added.

The International Award for Nature Conservation Merit was given in recognition of an outstanding contribution to peat-land conservation.

The presentation was made at Groenveld Castle in the Netherlands by the chairman of the Foundation, Prof Matthijs Schouten, in the presence of the Irish Ambassador to the Netherlands, Mr John Swift, and representatives of Dutch and international nature conservation organisations.

The Dutch Foundation for the Conservation of Irish Bogs was set up in 1983 to give international support to peat-land conservation in Ireland.

ENDS

Source: http://www.irishtimes.com/news/offaly-farmers-win-award-for-saving-raised-bog-1.221252

1989 – YEAR ZERO FOR SHARAVOGUE

In September 1989, a High Court injunction was served on a fuel merchant to prevent the exploitation of Sharavogue Bog which had been intact up to 1988.

During three days, a long perimeter drain and 21 transverse drains were mechanically inserted into the bog. It was to be the first stage in peat development at the site. However, an injunction was taken by two local farmers, who owned some of the bog and surrounding lands.

Two-thirds of the bog had no title recorded in the Land Registry, and the fuel merchant claimed that the title belonged to him, and other land owners.

The dispute that followed was based on trespass, but it was discovered this could not be sustained – in order to have been successful in preventing any further development on land in which no title is evident, one would need to have an interest in acquiring that land. The neighbouring farmers maintained that drainage to two thirds of the bog would have irreversibly damaged the remaining one third and the callow lands they owned.

But the old law in relation to ‘percolating water’ was against the conservation case: if you were a landowner, you cannot prevent damage to underground drainage on your land from drainage initiated by a landowner on neighbouring land.

The court case was to have taken place in 1990 but it never came to court. After a long and exhaustive search, the two local farmers and their solicitor managed to discover the original title-holder of the bog. They discovered the land was being held by a person living in England, and so a trip across the Irish Sea was made.

The title-owner was sympathetic to the cause of raised bog conservation, and subsequently agreed to sell the free-hold, jointly to Mr Patrick Headon and Mr Liam Egan.

Restoration and repair work was undertaken and the new owners entered a management agreement with Duchas (now the National Parks and Wildlife Service – NPWS).

Since 1990, any peat development over 50 hectares, such as that attempted at Sharavogue, is subject to Environmental Impact Assessment and planning must be obtained. This was a significant step forward for bog conservation in Ireland as mechanical extraction of this magnitude was very different from traditional cutting, like that with a sleán, which made little impact over the centuries.

SHARAVOGUE – THE BOG BY THE RAIL LINE

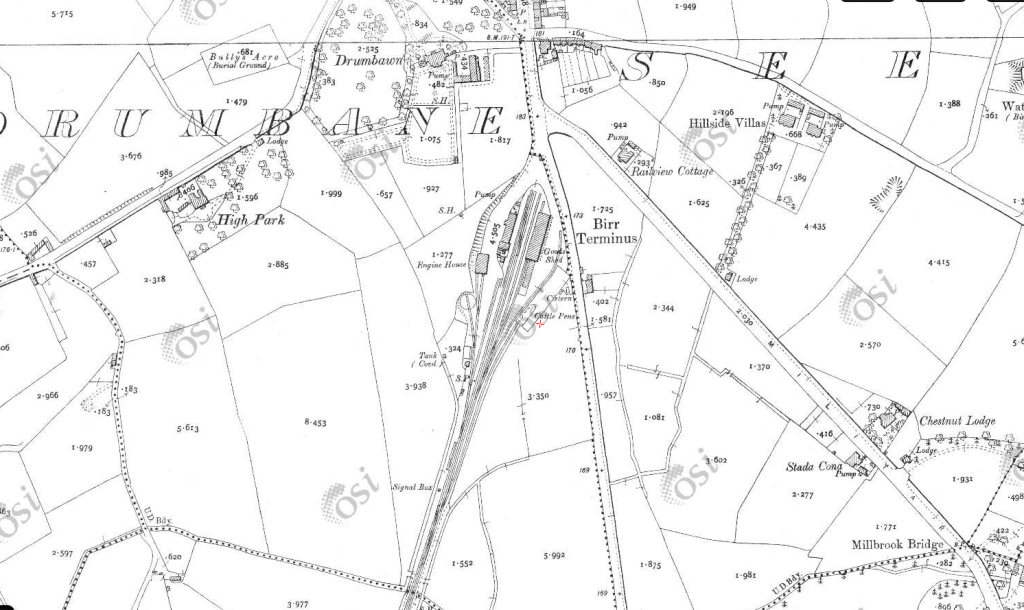

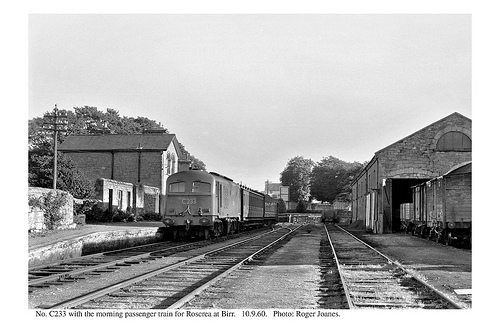

Last in line… The last train to use the Birr-Roscrea rail line which ran alongside Sharavogue Bog., pictured in 1960. Pic: Roger Jones.

Sharavogue Bog is bordered along its eastern edge by the remains of a disused rail line, which was once the Birr to Roscrea line, a 12 mile branch which linked Birr to the Dublin and Cork lines.

A section of the line went through the outer edges of the bog giving passengers on the twice daily service a tantalising glimpse of what at the time was a pristine raised bog. Indeed, the historic 25” maps record the line running along an uncut bog, with just a small handful of facebanks marked. A siding, the Sharavogue siding, is recorded in the National Library archives. Today, the outline of the track, in perfect curved lines along the bog is all that remains, together with some ruined buildings and sidings. The pics below show the line along the top and bottom of the bog.

In recent years there have been multiple proposals that the line – and others in the area including the Birr to Portumna, Ballybrophy to Limerick and Birdhill to Ballina lines – be developed for tourism. Greenways and cycleways along disused rail-lines have increased in popularity in Ireland in recent years with the Green Way in Mayo and the Old Rail Trail in Westmeath very popular amenities with locals and visitors alike.

The history of the line is intriguing; with its origins going back to 1853 when, after pressure from Lord Ross, a line between Ballybrophy and Birr (then called Parsonstown) to link up with the Dublin to Cork line was started.

In October 1857 the stretch between Ballybrophy and Roscrea was completed, with the Roscrea to Birr line completed in March 1858. It linked Roscrea to Birr for the next 105 years, until it eventually closed in 1963. There were at least two services daily, and trains left from an elegant rail station on the outer edges of the town.

The Birr to Roscrea line brought many visitors to both towns and was used as a route to the Monastery and a number of Holy Wells. People used it to get to the Our Lady’s Well at Clybanane, the Grotto at Fanure, the Holy Well near the former Cistercian Abbey Mill and others to get to the ‘Boiling Well’. The ‘Boiling Well’ is remembered by local man George Cunningham as a warm, natural spring well which bubbled, hence the name. It is just off the old Birr Railway line about 2 kms from Roscrea and near the Moneen (tributary of the Little Brosna).

It was also used by people with fishing rods instead of rosary beads, to get to the Brosna and Perry’s Well for fishing.

Four bridges are recorded on the line, of which two still retain their spans. The skew brick arch road bridge over the railway at Sharavogue, is one of only three arched bridges in Offaly to use this material. It is close to a former siding. Some of the old outbuildings are gone, but one exists alongside the bog, and it is believed what is now a house was once a station that served Shinrone.

The line closed in 1963, one of over a dozen branches to close forever that year. The last train to use it with passengers departed from Birr Station in September 1960. Photographer Roger Jones captured that occasion:

Birr station has long since been converted to a number of private residences with the goods sheds and other outbuilding in commercial and warehousing use (see below). The railway lines are all gone here but some remain along the line…

The Runaway Train

A notable event on the Birr to Roscrea line was the Runaway train crash of 1910 which occurred on the morning of July 19, 1910 when two trains, carrying between them over 800 passengers (most of them clergy) collided close to the bog. Some divine intervention must have been at play as no one was killed, despite over 400 people being injured, many of them seriously.

The drama started when a special train left Birr station to take over 750 pilgrims to Roscrea and onto Queentown (Cobh) where they would catch a ship that would eventually bring them to Lourdes. There was a fault with the brakes, so when the train arrived in Roscrea the driver uncoupled the engine, leaving the ten carriages on the Birr platform. Due to the numbers trying to get to Lourdes, four more carriages were to be added onto the ten.

As the four extra carriages were being shunted into place, the ten coaches were jolted and suddenly they moved out of the station and gathered great speed down the incline towards Birr. The line had a long slope between Brosna and Roscrea, with trains having to climb almost 50 metres over five kilometres.

Despite frantic efforts by the head porter, Mr Deering, and the station master, Mr Hayes to apply the handbrake, the carriages ran away at speed. In the distance they could see smoke down the line…. It couldn’t be… Yes, it was another train! The 09:15 from Birr was on the way towards Roscrea.

Deering waved a red flag, and others waved their hats from the runaway train, and luckily, the driver, Tim Broughall, and fireman on the 09:15 saw the commotion and had time to stop and begin backing their train back up the line. Sensing the obvious, many passengers on each train jumped – breaking arms, legs and other limbs as they flailed from the moving carriages onto the ground below. The trains collided at Fanure, just down the line from Sharavogue Bog.

The force of the collision was severe, but thanks to the evasive actions of the 09:15 driver, not as bad as it could have been.

The impact demolished the first four carriages of the runaway train, and it was the pilgrims on these who suffered the greatest injuries. Luckily, there were some nurses and doctors on board and monks from a nearby Monastery came to help. The army from the Leinster Regiment, stationed at Crinkhill also came. It’s not known if they grabbed some sphagnum from Sharavogue en route to the bog. At the time, sphagnum moss was used extensively by the army to treat wounds on battlefields abroad…

The aftermath of the 1910 train crash on the Birr-Roscrea line. Pic with thanks to Roscrea Through The Ages Facebook page)

Sums between a crown (25p) and 20 were offered as compensation, and the 76 seriously injured took these. Eventually there were 492 claims. The driver of the 09:15, whose actions undoubtedly saved many lives, Mr Broughall, was given shares in the GSW rail company.

The Stolen Line

The Birr-Roscrea line was successful in operation, but the same cannot be said for its neighbouring line, the so-called Stolen Line.

In 1863 a line between Birr and Portumna in Galway was started and it opened five years later as P. & P. B. R. or the Parsonstown & Portumna Bridge Railway. It was difficult to build with the bog at Curraghglass particularly hard to drain. The line was losing money from the start and the company behind it quickly built up debts. It closed in 1878, and swiftly became known as the ‘stolen railway’ after backers owed money, farmers and others began to steal property.

At first, no attempt at pillage was made at the Birr end, but a few miles out the country, the ballast started to disappear. It was found to be very useful in making farm roads and roadways into bogland. Next the fishplates, spikes and other small pieces of iron started to vanish. No doubt the blacksmiths of the time were glad to receive them, and it was said that ironmongers came from all over the country to engage in an early form of recycling.

The rails went next and they were put to many uses. The sleepers were taken up and together with the rails were used for sheds and other farm buildings – and even firewood. The thieves came from far and near and worked quickly. After a few days, nothing but the bed of the railway remained.

The station house in Portumna was allegedly stripped clean and effectively demolished in one night! Many homes and outhouses were fitted with the timber, windows, doors, slates, kerbs, and paving stones.

An attempt was made to remove the girders of the six span bridge over the Little Brosna at Riverstown, but the attempt was thwarted by the local RIC.

Some marauders were brought to court, but nobody could be found to represent the company. This paved the way for a wholesale grab of what was left and practically every trace of the line and its infrastructure was looted.

Historian Joe Coleman wrote of the prevailing feelings in the immediate area in the Irish Railway Record Society: “Even today people in the area people are reluctant to talk about the P&PBR. Some will say that the whole line disappeared in a single night, others will either claim that they never heard of it, or if they have, they will blame the people of East Galway for stealing it. However, without looking in any particular direction, there is much evidence to suggest that the railway didn’t go too far away in the end.”

Useful Links:

For mere on ‘The Stolen Line’ see Seamus J King’s piece HERE and also Joe Coleman’s Irish Railway Record Society piece HERE and a New Zealand academic paper HERE

Newspaper report of Portumna – Birr- Roscrea Greenway plan

Railways Archive (including accident report)

MONUMENTS AND INTERESTING FEATURES

The nearest recorded monument to the bog is immediately to the east of the rail line at the top, northern end of the bog, where there is evidence of a large circular enclosure in the townland of Kilnalacka. According to the National Monuments Service, no surface remains visible, but the levelled monument was situated on a flat pastureland to the east of the bog. It was depicted as a large circular enclosure or platform on first two editions of the OS 6-inch maps. Later it was depicted not as an antiquity, but as a roughly oval-shaped grove of trees on the 1908 ed. OS 25-inch map.

In the townland of Rathbeg to the east of the bog (indeed, the bog is sometimes referred to as Rathbeg Bog) there lies the remains of a ringfort or rath. It is situated on high ground in an upland area. According to the National Monuments Service, the large circular area (diameter 40m) is enclosed by two earth and stone banks with intervening fosse (3m) and impressive causewayed entrance (4m) at the south west. The inner bank (Wth 2m; ext. H 0.7m) is reduced to a scarp in places and has a modern gap (3m) at its north end. There is a large quantity of stone in the better preserved outer bank (Wth 3m; ext. H 0.5m; int. H 0.75m) which may be due to field clearance debris. There is no evidence of an external fosse.

Just above this site is another enclosure in Ballyegan which is a barely discernible outline of a destroyed enclosure consisting of a circular area (diam 43m) located on flat pasture land. Depicted as large circular enclosure on 1912 edition of the OS 6-inch map.

There are further ring forts in the townlands of Ballygaddy (Clonlisk By) over the N62 and Ballincor Demesne, and Boveen. A Fulacht Fia was located in Clonkelly to the north west of the bog, in the 6-inch OS maps but has since been levelled and there is no evidence of it.

The above descriptions are derived from the published ‘Archaeological Inventory of County Offaly’ (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1997).

Holy Wells and St Patrick

The landscape all around Sharavogue Bog and between Birr and Roscrea is dotted with Holy Wells. Many are not recorded on more modern maps, but are visible from the old OSI Maps (available online HERE) and the HISTORIC VIEWER from the National Monuments Service and Department of Arst, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs.

People used it to get to the Our Lady’s Well at Clybanane/the Grotto at Fanure, the Holy Well near the former Cistercian Abbey Mill and others to get to the ‘Boiling Well’, close to Roscrea. The ‘Boiling Well’ is remembered by local man George Cunningham as a warm, natural spring well which bubbled, hence the name. It is just off the old Birr Railway line about 2 kms from Roscrea and near the Moneen (tributary of the Little Brosna).

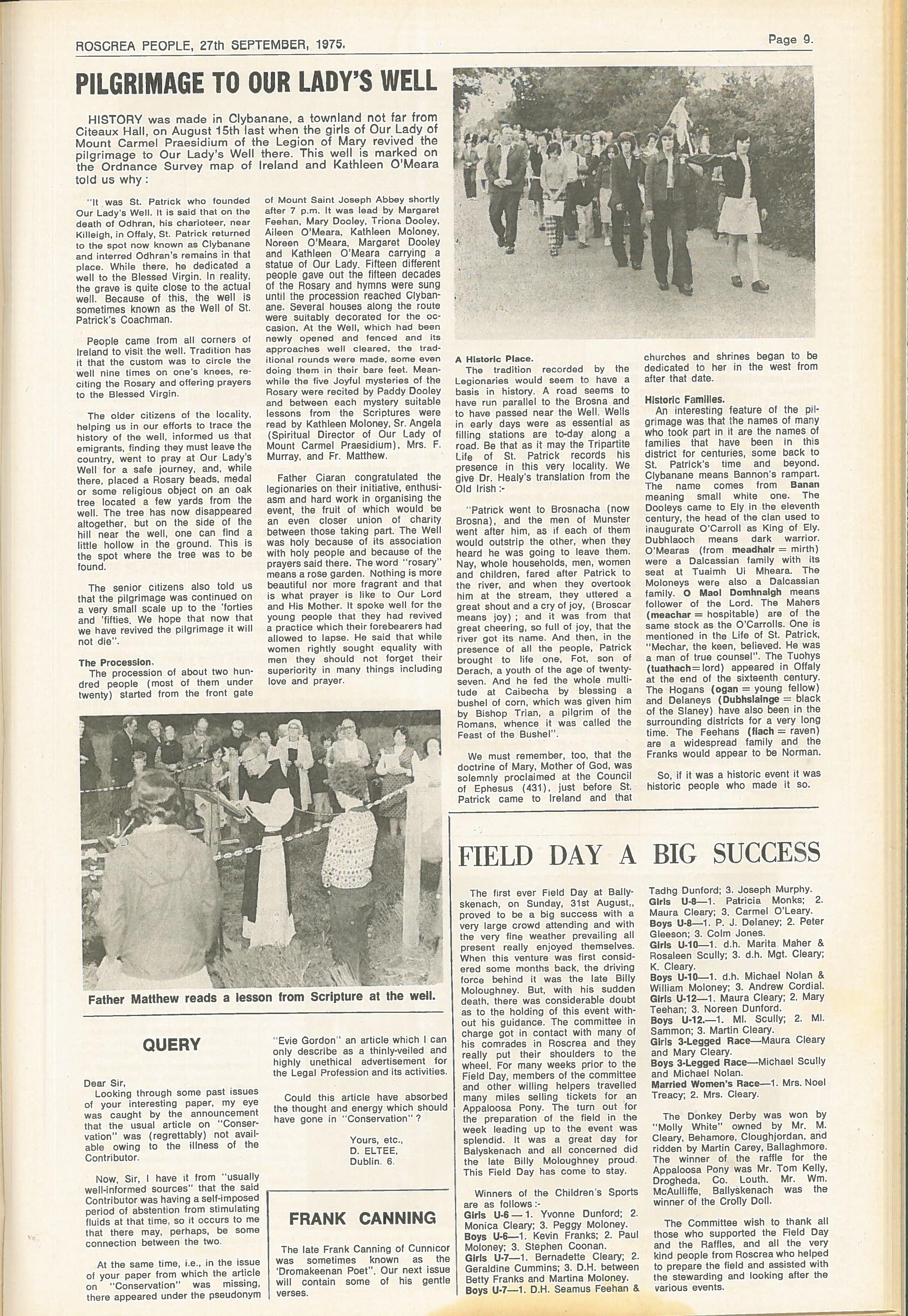

With thanks to Offaly County Heritage Officer Amanda Pedlow and the Roscrea People we below republish an interesting article from 1975 about a local attempt to revive the Pilgrimage to Our Lady’s Well at Clybanane.

It was said that none other than St Patrick founded the well. On the death of his charioteer Odhran, near Killeigh in Offaly, St Patrick returned to the spot known as Clybanane (near Fanure) where he interred Odhran’s remains. Whilst there, he is said to have dedicated a well to the Blessed Virgin. People from all corners of Ireland would pray at the well for a safe journey, and a nearby oak tree (now gone) was adorned with religious objects. The well became known locally for many years as ‘The Well of St Patrick’s Coachman’, and some referred to it as the Grotto. Pilgrimages died out in the 1950’s, until the August 1975 revival, detailed below:

The current conservation objective for Sharavogue Bog is to restore the area of Active Raised Bog to the area present when the Habitats Directive came into force in 1994.

It is hoped to increase the area of Active Raised Bog to over 40 hectares. It is estimated that ARB cover on the high bog area currently stands at approximately 25 hectares. Restoration works here were undertaken by contractors in 2021 with over 400 dams installed. These have helped re-wet the bog, increase the areas of Active Living Raised Bog, store carbon, clean water, increase biodiversity and generally make this impressive bog an even better place than it already was.

‘The Living Bog’ carryed out a range of habitat restoration techniques. These include installing hundreds of new peat and plastic dams to block drainage channels which have been causing the bog to lose water. Disturbed peatland surfaces will be improved to enhance the capacity of both lobes of the bog to restore through greater hydrological connectivity, improving its ecological condition and coherence. By re-wetting the disturbed and ditched habitats, a higher water table will be created, benefiting a range of rare bog species and in time, a more sustainable natural raised bog habitat will be restored to Sharavogue Bog.

A typical high bog drainage channel blocked by peat dams. We will be using man and machine to block drains at Sharavogue Bog SAC

Restoration works by NPWS took place at the site throughout the 1990s including the blocking of high bog drains and the cutover drains in the southeast. An initial failed attempt at drain blocking took place in 1992, but a successful one was undertaken in the 1994-1999 period. Fernandez et al. (2005) already reported considerable increases in Active Raised Bog in the middle section of the high bog as a result of the drain blocking. No further increase in habitat area has been noted in the 2005-2011 reporting period.

The area of ARB was reported as 25.8 ha during the latest monitoring survey (2011) and it was concluded that 14.7 ha of Degraded Raised Bog (DRB) on the high bog can be restored to ARB with the appropriate restoration measures. There is also long-term potential for 0.4 ha of bog peat-forming habitats to develop if restoration measures are undertaken on cutover areas.

A plastic dam at another site. If sphagnum moss and other vegetation grows on the pool and dam it is a sign that you have built a healthy dam and ARB is developing well.

Sharavogue Bog SAC is a site of considerable conservation significance as raised bogs are a rare habitat in the E.U. and one that is becoming increasingly scarce and under threat in Ireland. It contains good examples, covering significant areas, of the E.U. Habitats Directive Annex I habitats Active Raised Bog, Degraded Raised Bog (which is being restored to the priority Annex 1 habitat Active Raised Bog) and Depressions on peat substrates (Rhynchosporion). The site already supports a good diversity of raised bog microhabitats, including some hummock/hollow complexes, and rewetted cutover bog.

Ireland has a high proportion of the total E.U. resource of Atlantic raised bog (over 50%) and so has a special responsibility for its conservation at an international level. Along the eastern margins of Sharavogue there is upwelling base-rich ground water in the lagg zone which supports carr woodland and calcareous fen vegetation. Areas of wet lagg vegetation such as this are very rare in Western Europe and the lagg system at Sharavogue is one of the best developed in the country. The protected semi-aquatic plant species Slender Cottongrass (Eriophorum gracile) is growing in fen vegetation in the lagg zone, while the nationally rare shrub Alder Buckthorn occurs in dry bog woodland on cutaway. the lag zone is also home to a number of rare animals and invertebrates.

All the typical vascular plant species for the Active Raised Bog habitat such as Heather (Calluna vulgaris), Cottongrasses (Eriophorum angustifolium and E. vaginatum), Deergrass, Bog Asphodel and White Beak-sedge are common and the Midland raised bog indicator species Bog-rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) and Cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos) are present.

Round-leaved Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) and Bog-Cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos), a Midland raised bog indicator species, are both present at Sharavogue

The dominant micro-topography consists of Sphagnum hummocks and hollows. Pools are scarce and Sphagnum cuspidatum filled lawn-like depressions are very occasional. The overall Sphagnum cover ranges from 51 to 75%. The wettest areas are characterised by the abundance of Cottongrasses (Eriophorum vaginatum and E. angustifolium). Hummocks consist of Sphagnum capillifolium, S. papillosum, S. magellanicum, S. tenellum, S. subnitens and very occasionally S. fuscum and S. austinii. Hollows may contain S. cuspidatum and/or S.tenellum.

Whilst the surface is generally quite dry, there are some small pools and lawns where Rhynchosporion vegetation is well represented. Rhynchosporion habitat is best developed in the extensive wet cutover present along the eastern margin of the high bog area. Here the dominant species are Sphagnum cuspidatum, White Beak-sedge, Common Cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium) and Great Sundew (Drosera anglica). The rare Brown Beak-sedge also occurs. There are a number of pools on the high bog that also support Rhynchosporion vegetation. Rhynchosporion vegetation is also well-developed in extensive wet cut-away areas which occur along the eastern margins of the high bog. Other plant species of the raised bog which are less common are Bog-rosemary, Cranberry and Round-leaved Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia).

Round-leaved Sundew, aka Drosera Rotundifolia, one of Ireland’s carnivorous plants which gets its nutrients from trapped insects.

Within the cutover zone along the eastern margins of the site there is upwelling of base-rich water and these areas now support carr woodland and calcareous fen vegetation.

The vegetation of old cutover at the site is of ecological interest, particularly along the eastern margin of the bog, where a spring-fed, species-rich fen is found at the base of a limestone ridge. It is thought that this fen vegetation is a remnant of a much more extensive lagg zone, which once flanked the entire eastern side of the bog (Conaghan 1998).

This feature of a base-rich lagg area, in close proximity with the high bog, is unique in the context of Irish raised bogs (Kelly et al. 1995). The vegetation of the eastern lagg has recently been described by Conaghan (2014). The lagg can be divided into two sections, a northern zone and a southern zone. The northern area is principally cutover bog with ombroptrophic influences dominant. The surface is relatively dry in this area with some scrub encroachment (Conaghan 2014). In contrast, the southern zone has a notable minerotrophic influence with areas of Schoenus nigricans dominated fen vegetation typical of base rich conditions. The fen areas are associated with pools and occur in a mosaic of woodland, scrub, and cutover bog. Between and amid the fen areas and the railway embankment to the east, is a narrow strip of alder carr. The recent survey of the eastern lagg zone has concluded that the vegetation in this area has not changed significantly during the period 1997-2013 (Conaghan 2014).

Areas of wet lagg vegetation such as this are very rare in the country and the lagg system at Sharavogue is one of the best-developed in the country. The rare semi-aquatic plant species Slender Cottongrass (Eriophorum gracile) has been recently discovered growing in fen vegetation at this site. This species is legally protected under the Flora (Protection) Order, 2015.

The nationally rare shrub Alder Buckthorn (Frangula alnus), a Red Data Book species, occurs in dry bog woodland on cut-away. On the western side the site, the vegetation grades from high bog, through fringing woodland, to alluvial wet grassland by the Little Brosna River.

Fauna of Sharavogue Bog

The common frog (Rana temporaria) is known to occur. Irish hare (Lepus timidus hibernicus) was reported as common, with badger (Meles meles), fox (Vulpes vulpes), otter (Lutra lutra), pine marten (Martes martes), mink (Mustela vison), stoat (Mustela erminea) and fallow deer (Dama dama) also found in the SAC (NPWS, 2004).

Snipe (Gallinago gallinago), pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), curlew (Numenius arquata), woodcock (Scolopax rusticola), meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis), skylark (Alauda arvensis) and mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) have been reported as breeding on the bog.

Other birds that have been known to frequent the SAC include sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), teal (Anas crecca), long-eared owl (Asio otus), barn owl (Tyto alba) and grey heron (Ardea cinerea) (NPWS 2004).

The spider fauna of Sharavogue has been subject to recent survey (Myles Nolan) who found there to be five rare species of spider on Sharavogue Bog:

Hypsosinga albovittata – This distinctively marked spider spins its orb webs low down, less than 20 cm above ground level (Jones 1983), usually on heather.

Minicia marginella – few records in Ireland and particularly in the UK.

Satilatlas britteni – only 10 records in Ireland according to the National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Simitidion Simile – quite rare

Walckenaeria alticeps – very rare member of the family Linyphiidae who loves bogs and Sphagnum in particular.

Moorkens (1998) reported on the mollusc fauna of the SAC, report to follow.

Situated south of the historic Offaly town of Birr, Sharavogue Bog is one of Ireland’s best preserved raised bogs. Sharavogue Bog is also one of the few remaining raised bogs in Ireland situated on a floodplain. It has a well-developed dome of uncut peat which is long and relatively narrow. Restoration prospects here are very good.

Like our Westmeath project site Garriskill, it is bounded by a decommissioned public rail line on one side (the Birr-Roscrea line, see History section) and a river on the other – and it boasts a connection to no less a person than Saint Patrick! Turf cutting here never really reached the levels it did elsewhere in Offaly, though a large section to the north of the bog was extensively cut in the early 1900’s. But the main active raised body of the bog remains and its good condition is testament to two local men who worked together to save the bog from heavy machinery harvesting in the 1990’s. Drainage channels were dug across the bog sometime in the early 1990’s and only for the actions of Mr Liam Egan and Mr Patrick Headon, Sharavogue could have been lost forever.

The total site covers 223.43 ha and is situated between the River Little Brosna and an elevated ridge of Carboniferous limestone. It includes 137 ha of uncut raised bog and 86 ha of surrounding areas which include cutover bog, wet grassland, semi-natural woodland, and an area of wet lagg vegetation in the cutover along the eastern margin of the bog. The eastern edge is bounded by a disused railway embankment, which once linked Birr to Roscrea, and the western edge by the Little River Brosna.

Restoration works here were undertaken by contractors in 2021 with over 400 dams installed. These have helped re-wet the bog, increase the areas of Active Living Raised Bog, store carbon, clean water, increase biodiversity and generally make this impressive bog an even better place than it already was.

The bog is underlain by low permeability limestone and limestone till.

The site is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) selected for the following habitats and/or species listed on Annex I / II of the E.U. Habitats Directive (* = priority; numbers in brackets are Natura 2000 codes):

[7110] Raised Bog (Active)*

[7120] Degraded Raised Bog

[7150] Rhynchosporion Vegetation

Active Raised Bog (ARB) comprises areas of high bog that are wet and actively peat-forming, where the percentage cover of bog mosses (Sphagnum spp.) is high, and where some or all of the following features occur: hummocks, pools, wet flats, Sphagnum lawns, flushes and soaks.

The LIFE team will publish its results in late 2021, but the most recent studies from 2011 and 2002 indicated that ARB cover on Sharavogue is high, over 25.8ha of the high bog area, mainly in the central and southern part of the dome. With restoration works to be carried out on site between 2017 – 2020 we aim to increase this to over 40h on the high bog. Prospects for restoration here are positive.

Degraded Raised Bog (DRB) corresponds to those areas of high bog where the hydrology has been adversely affected by peat-cutting, drainage and other land use activities, but which are capable of regeneration to ARB within 30 years.

The area of (DRB) on the High Bog was modelled as 29.5ha (by Fernandez et al. 2012), mainly on the southern dome but it lacks many extensive areas of quaking hummock/hollow/pools as a result of long-term drying out caused by peat cutting, burning and marginal and river drainage.

Many of the drains inserted on the high bog in the 90’s and on the south eastern area of the cutover were dammed in the late 1990s as part of an E.U. Cohesion project to restore peat forming conditions. That project was successful in halting and reversing, to some extent, the decline of ARB on the site.

The Living Bog built on this work, restoring and increasing the area of Active Raised Bog by almost twice its current amount. In time, our restoration work will lead to an even bigger increase…

‘Galway’s Living Bog’, aka Carrownagappul Bog SAC, just outside Mountbellew, is one of the biggest, most accessible raised bogs in Ireland. It has been at the centre of local community life for generations, and now welcomes people from all over the world to visit it. And why not? Not only is it one of the best examples of a raised bog West of the River Shannon, it is one of the most beautiful bogs in all of Europe.

At almost 1,200 hectares, it is the second biggest Living Bog project site, and thanks to its condition (plenty of raised bog and unique flora and fauna), its folklore and its location Carrownagappul has the potential to become one of Ireland’s foremost bogs to visit. You can learn a lot by visiting it, or by popping into the Interpretive centre at Galway Teleworks/Mountbellew Mart, just a few km from the bog.

The bog contains one of the largest extant areas of uncut high bog surface in all of Galway. It is also the most negotiable bog in all of Galway, traversed by a road and track network and thanks to areas like the historic Patches Garden right at the heart of the bog, it is a peatlands amenity with huge potential. Every single aspect of the Irish peatlands story is contained within its SAC boundary, and with a history going back over 9,000 years, it is a bog with a great story to tell!

Restoration works here took time, as there was numerous open drains (many of them hidden, other treacherously deep) and almost 25kms of them were blocked by The Living Bog team on the high bog alone. Careful assessment of the bog took place between 2016 and the commencement of restoration works here in January 2019. Works were completed April 2019, with additional works undertaken in September 2019 and again in 2020. In all, over 3,000 peat dams were required to encourage active raised bog growth on the high bog and cutover bog. Seveal large-scale plastic dams were also developed by The Living Bog to block particularly wide drains which were taking millions of gallons of water off the bog.

Numerous bog roads, tracks and drains extend into the centre of the site. Until very recent years, peat extraction occurred frequently along the margins of the site and along the bog roads. This turf cutting went back hundreds, if not thousands of years.

From surveys over the years it was established that some very low relief eskers run under the bogs. A till island lies in the centre of the site and this is not covered by peat. This island is known as ‘Patches Garden’ on account of its last occupant, Patch Cronin. This area is at the heart of both the bog and amenities on site. Looped walks all start and end at Patches Garden, and a special park is to be opened there in 2021 as part of Living Bog amenity plans on site.

This bog is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) selected for Active Raised Bogs 7110, Degraded Raised Bog 7120 and Depressions on peat substrates (Rhynchosporion) 7150 – habitats that are listed on Annex I of the EU Habitats Directive (992/43/EEC), where Active Raised Bogs 7110 is further ranked as a “priority” habitat.

The Living Bog team have been surveying the bog since the project was established in 2016, and the results will be published here in due course. Already, some figures are above those from previous surveys.

Prior to the Living Bog, survey results (Raised Bog Monitoring Project 2013 (Fernandez et al.)) showed Active Raised Bog covers 28.07ha (8.68%) of the high bog area. High quality Active Raised Bog consists of both central ecotope and active flush. High quality Active Raised Bog comprises only 4.12ha, consisting of both central ecotope (2.74ha) and active flushes (1.38ha). The micro-topography of central ecotope consists of pools, low hummocks, high hummocks, hollows and lawns, and the wet ground is mostly very soft to quaking.

Total Sphagnum cover is in the range of 76-90%.

Sphagnum Cuspidatum on a healthy section of high bog

Degraded Raised Bog covers 295.41ha (91.32%) of the high bog area. It is drier than Active Raised Bog and supports a lower density of Sphagnum mosses, although Sphagnum cover is in the range of 30- 40% in the wettest of the sub-marginal community complexes recorded, and between 26-33% in some of the other wetter complexes. Degraded Raised Bog has a less developed micro-topography, and permanent pools and Sphagnum lawns are generally absent.

Prior to Living Bog, small scale restoration works, in the form of drain blocking on the high bog, took place at the site, but the high bog is extensively drained and the greater part of the drainage network remains unblocked. Several drains in the southern section of the high bog have been dammed, and the positive effects of this action have been recorded in the last survey, with Fernando reporting a 9.87ha increase in Active Raised Bog habitats, at the expense of former sub-marginal ecotope. These improvements were recorded over a substantial part of the southern section of the bog.

The current conservation objective for Carrownagappul Bog is to restore the area of Active Raised Bog to the area present when the Habitats Directive came into force in 1994. In the case of Active Raised Bog, the objective also includes the restoration of Degraded Raised Bog. The Area objective for Active Raised Bog is 73.06ha (comprising 64.55ha on high bog and 8.51ha on cutover).

Early indications from 2020 surveys and 2021 surveys indicate we are on course for this – if not the creation of even more!