History

The last Ice Age had a major influence on the Irish landscape, and Clara Bog is one of the finest examples of what it left behind. To the north of the bog, an esker runs in an east-west direction. Eskers, steep ridges of layered sand and gravel, were laid down by retreating glaciers over 10,000 years ago. The low-lying area became a large, shallow lake. As thousands of years went by, this became a raised bog…

Plants started to grow around the edges of the lake and in time, these plants extended over most of the lake’s surface as it became infilled with dead plant matter. As this partly decayed plant matter (fen peat) grew above the influence of mineral rich groundwater or surface waters, sphagnum mosses and other plants which could thrive in a nutrient-poor rainwater-fed environment, began to dominate.

They died, but did not decompose as soil microorganisms in the acidic, waterlogged, low oxygen environment and the dead moss accumulated as sphagnum peat. This process, which started around 7,000 years ago, continues to this day.

The accumulation of peat was greatest in the centre and least around the margins, where decomposition of the plant material was faster. This gave the bog a high dome shape, raised up above the surrounding land, to which the name ‘raised bog’ refers. Clara was once one great dome, rising high above the eskers around. But, as detailed below, a modern road dissected the bog and ‘punctured’ its great dome.

Clara Bog contains all the classic components of a raised bog: fine examples of hummocks, hollows, mossy lawns, pools and flushes. It is rich in wildlife with hundreds of diverse species of flora and fauna calling Clara home. At Clara, a special feature are the soak systems, open water areas and very wet spots, where nutrients are more available and which support a more diverse plant life than in the surrounding bog. Two such areas are Lough Roe and Shanley’s Lough. However, a lot of the other soak systems, pools and lakes on the bog were affected by human influence.

Split Personality

Even though vast swathes of Clara Bog were harvested by man and machine over the past 200 years, Clara Bog has been much less exploited than many other Irish raised bogs and has remained relatively intact. However, thanks to the Clara-Rahan road, which runs directly through the site, the bog has something of a split personality as it is now split into Clara East and Clara West.

The construction of the road (and associated drains), beginning in the late 18th century, bisected the bog and causing it to subside by up to several metres. Locals recount stories of how the bog had a huge central dome shape, rising between 6 to 10 metres in height. But it now has two domes, one on Clara West and one on Clara East. Their height is not as great as what the central dome would have looked like, thanks to subsidence of the bog towards the road on either side. The drainage channels dug to accommodate the road would have had a huge impact on this.

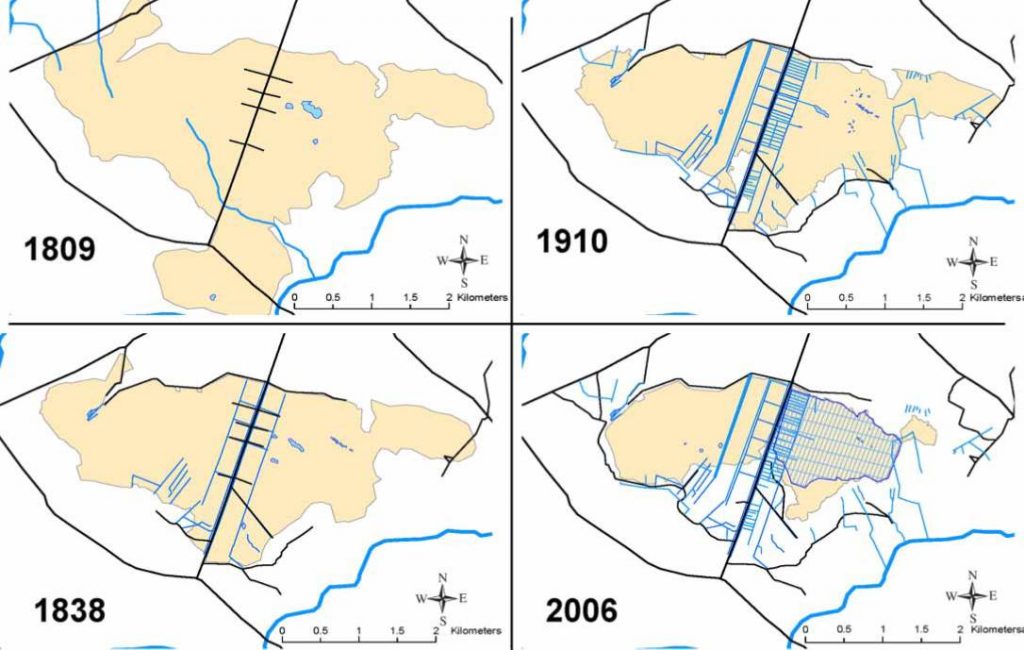

The major changes on Clara Bog and the surrounding landscape as evident from historical maps. Sources: Larkin 1809, Ordnance Survey 1840, 1912, 2000. Crushell et al, 2008. Irish Geography, Vol 41, No. 1, 89-111

Drainage of the entire bog began in earnest in the early 1800s, and as you can see from the above illustration, only a small piece of what was originally mapped remains. In 1809 the high bog was estimated to cover some 1,014 hectares. At present, it is estimated to be 443 hectares (or 44%).

Peat extraction came mainly inwards from the road, and from the southern, Rahan end. It carried on at a small-scale for decades until the ante was upped from the 1950’s onwards when more industrial methods of peat extraction became commonplace on both sides of the bog.

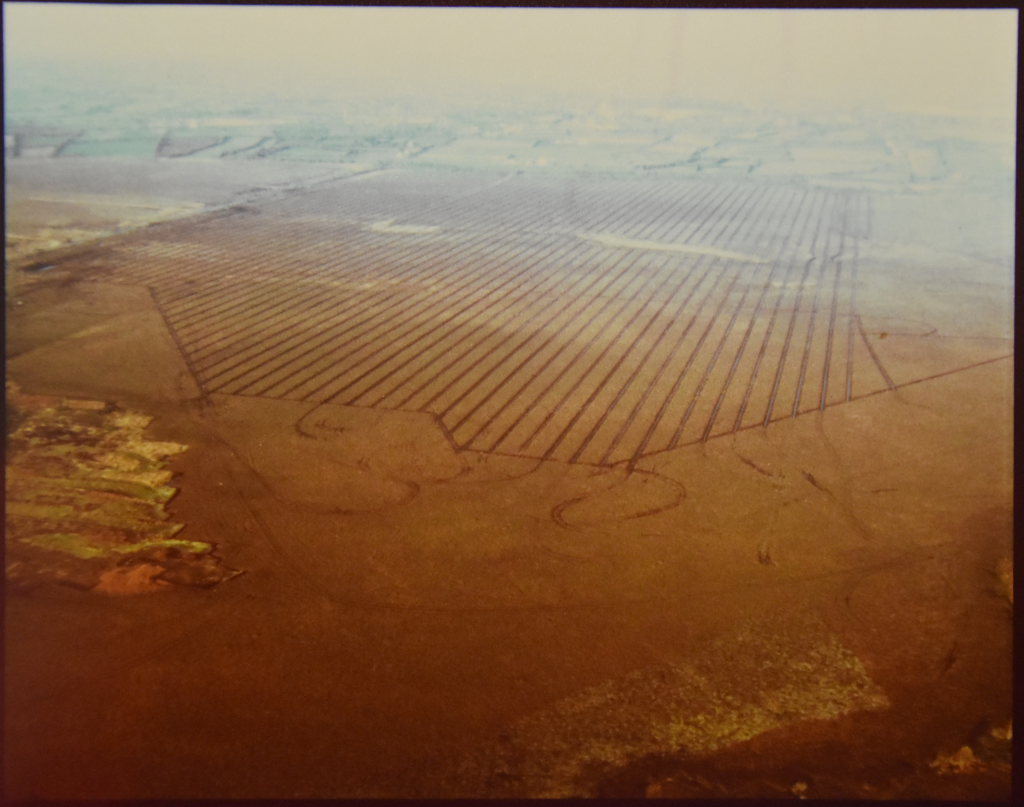

In 1983/1984, a dense network of surface drains were dug on Clara Bog East in preparation for commercial peat extraction.

The drainage channels dug into Clara East in 1982-1983 photographed from the air not long after they were dug. (Pic: Irish Peatland Conservation Council)

Had this extraction taken place, Clara East would effectively have been lost forever. But thankfully, the extraction never happened, and with works undertaken in the 1990’s, these drains have now been blocked. Hundreds of drains dug by specialist heavy machinery were blocked by a small team of men, mainly blocking them with hand-cut peat dams, thus saving the bog.

NPWS staff members Colm Malone (right) and Noel Bulger giving a dam building demonstration on Clara in 2016. Colm was a member of a team which created thousands of these dams over a short number of years on Clara East.

Clara became the site of intensive research in the 1980’s and a growing appreciation of its value reached the highest offices. Turf cutting and peat extraction eventually stopped on Clara in 2012. Many turf cutters chose a nearby re-location site to carry on the tradition. Back at Clara, old face banks and drainage associated with past cutting continues to cause far-reaching and negative impacts on the high bog habitats, threatening its soak systems and surrounding Active Raised Bog habitat.

Much restoration work remains to be done in order to conserve this bog. The results will be closely monitored, especially as Clara Bog is one of the most studied in Europe and has been the focus of national and international scientific investigation for many years. Studies are ongoing at the bog, alongside the LIFE project.

‘Probing the Past: A Natural History of Clara Bog’ by the National Parks and Wildlife Service